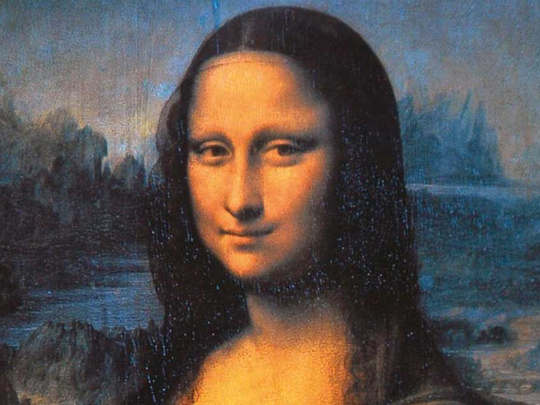

If Leonardo da Vinci had painted his Mona Lisa in the 21st century instead of the early 16th, he’d have netted a fortune from merchandising and repro rights alone. A snap survey of my own shelves reveals the face of Lisa del Giocondo, an otherwise unsung middle-class Florentine housewife and mother, on several book jackets, a used Paris Museum Pass and a jokey flip-book titled C’mon Mona - Smile!

Leonardo’s portrait was admired in his lifetime; it was subsequently among the most treasured possessions of the French king Francis I and Napoleon, who hung it in his bedroom. From here it passed to the Louvre. The Mona Lisa’s present life as the most egregiously pirated painting in history did not, however, begin until August 1911, when it was stolen by Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman who believed (erroneously) that he was repatriating Napoleonic loot to his native country.

Nineteenth-century developments in print technology and photography made it possible, as it hadn’t been before, for reproductions of art to reach a mass audience. Illustrated newspaper reports of Peruggia’s theft turned a masterpiece into a celebrity. At which point, you could say, the Mona Lisa became public property, a legitimate target for both satire and idolatry.

In 1919, Marcel Duchamp drew a moustache on a print of the painting. And this is nothing to what you can find online today. By defining a reproduction of art as a mass-produced “ready-made”, Duchamp opened the door for consumer goods, for anything at all, to take the form of art. Mona Lisa sneakers, socks, duvet sets, toothbrush holders are all just a click away.

Martin Kemp is an art historian, Leonardo expert and emeritus professor at Oxford; Pallanti is an economics teacher who has spent years researching the del Giocondo and da Vinci families. They have teamed up to write Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting. And, while they acknowledge the proliferation of “Leonardo lunacies” in the quest for the truth about the painting, their book is a model of clear-headed rationality, succinct, intriguing and marvellously readable.

By focusing on the world’s most famous artwork (not even Van Gogh’s Sunflowers series comes close), they set themselves a challenge that is probably unique. In the attempt to stimulate interest in less well-known works, art historians usually have to convince readers that they have discovered hidden meanings far more surprising than anyone had guessed. With the Mona Lisa, it’s the opposite case.

This small painting, which started as a run-of-the-mill portrait commission, has been the subject of unparalleled efforts of scholarship and forensic examination. It has entered the popular imagination and inspired innumerable crackpot theories.

Kemp and Pallanti’s mission is to show that the truth is simpler, or at least more comprehensible, than you would have thought possible. Other academics might have required a doorstop tome to contain the fruits of their combined archival and art historical research, but Kemp and Pallanti condense their findings into fewer than 300 pages.

Rich in evidence and judiciously light on speculation, their 11 brisk chapters cover multiple lines of inquiry leading to and from the Mona Lisa. These include genealogy and social history, the nature of Renaissance record-keeping and love poetry, and Leonardo’s own multi-disciplinary creative output, from canal design to tournament paraphernalia, not to mention portrait painting.

One of their revelations is the identity of Leonardo’s mother, who turns out to have been an orphaned teenager named Caterina di Meo Lippi. In July 1451, she met with the 25-year-old lawyer Ser Piero da Vinci, who was visiting his family village near Florence.

Piero promptly returned to the city, leaving Caterina to discover that she was pregnant. She went to his parents, who took her in (there was nothing unusual about her predicament), probably provided a modest dowry to enable her to find a husband, and raised her baby, Leonardo, as their own.

Kemp and Pallanti’s positive identification of Caterina is based on uncovering “detailed histories of obscure and struggling families”. It is less colourful than the alternative hypothesis that she was a North African slave, but seems likely to be definitive. So too does the intricate network of kinship and social-professional contacts they map for the main families in this story. The names and circumstantial details meticulously inscribed in tax assessments, notarial agreements and domestic inventories enable them to construct vivid snapshots of many people who played a part in Leonardo’s young life and developing career.

There’s his alpha-male lawyer father. Despite losing successive young wives to death in childbirth, Ser Piero went on siring children into his 70s, moving into progressively grander houses as his fortunes and family grew. A sharp dresser with a penchant for paonazzo (a luxurious red-violet colour), he seems to have passed on his eye for classy threads to his son - witness the “improvisation on veils, layers, folds, spirals, opacity, translucency, textures and restrained colour” of which the Mona Lisa’s clothing consists.

Then there’s Lisa herself, whom Kemp and Pallanti set out to rescue from the excesses of her posthumous fame. Born Lisa Gherardini in 1479, she was married at 15 to a much older merchant, Francesco del Giocondo. Other residents of their neighbourhood in Florence included Botticelli, Michelangelo and Raphael, but it was from Leonardo that Francesco commissioned his wife’s portrait in 1503. Lisa probably sat for a drawing or two; Leonardo got to work on the painting, gave up, sporadically returned to it over the next few years, and finally decided never to let it go. We learn, among other minutiae, that on August 11, 1514, Lisa bought seven lire worth of medicinal snail water from the nuns of Sant’Orsola, and that on September 8, 1523, she sold these same nuns 40 kilograms of cheese.

So now we know.

But do these kinds of semi-connected moments, easy enough to visualise in Mona Lisa: The Movie, make any difference to the way we see Leonardo’s painting? Strangely enough, within Kemp and Pallanti’s terms, they do. Their book conveys particularly cogently the unprecedented breadth of Leonardo’s interests.

He could not see a bird flying without wondering how it stayed in the air, or a river without working out what made it flow. No detail was too ordinary to engage his mind (“So, Lisa, what’s that snail water for?”). No apparently self-evident fact was capable of satisfying his desire to understand. We imagine him drawing the young woman and asking himself the familiar questions about exactly what it was that made her beautiful.

Around the time he began Lisa’s portrait, the Florentine government employed Leonardo to mastermind an ultimately unsuccessful project to divert the River Arno from the rival city of Pisa. His hydrological observations led him to believe that the human circulatory system resembled a watercourse.

The authors don’t make a big deal about Leonardo’s genius. They invite you to follow his thinking, step by step, leap by leap. Sometimes you’re not sure where it’s going. Then, suddenly, the pieces come together, and the Mona Lisa makes sense, as the “supreme vehicle into which he poured his powers... his personal expression of what the ‘science of painting’ could accomplish”.

Her unprecedentedly direct gaze, the conundrum of her clothes, the imperceptibly delicate brushwork of her flesh - like a denouement in crime fiction, you finally get the motives that make sense of everything.

Almost equally fascinating are modern scientific attempts to reconstruct the Mona Lisa as she might have looked at different times in Leonardo’s studio. X-rays and infrared reflectography provide ambiguous evidence about his techniques and alterations, while the latest Layer Amplification Method (LAM), pioneered by Pascal Cotte, has resulted in a digital restoration of the “original” Mona Lisa, a safe alternative to laying hands yet again on the damaged, much-restored painting.

For all its virtues, Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting is far from the end of the story. I know this because something has happened since I finished reading it. I can’t get the Mona Lisa out of my head.

The sitter’s indescribable aura of both startling presence and spectral remoteness, the dreamlike landscape fading to blue - I’ve caught the bug again. What can be done? I can’t face another visit to the Louvre, launching into the crowd for my few prison-interview moments with the beleaguered little portrait encased in bullet-proof glass. There has to be another way to get close to the real Mona Lisa. Maybe I just need to give in and order that duvet set.

Michael Bird’s latest book is George Fullard: Sculpture and Survival. His radio feature Frost-Heron was broadcast on June 11, on Radio 3 at 6.45pm