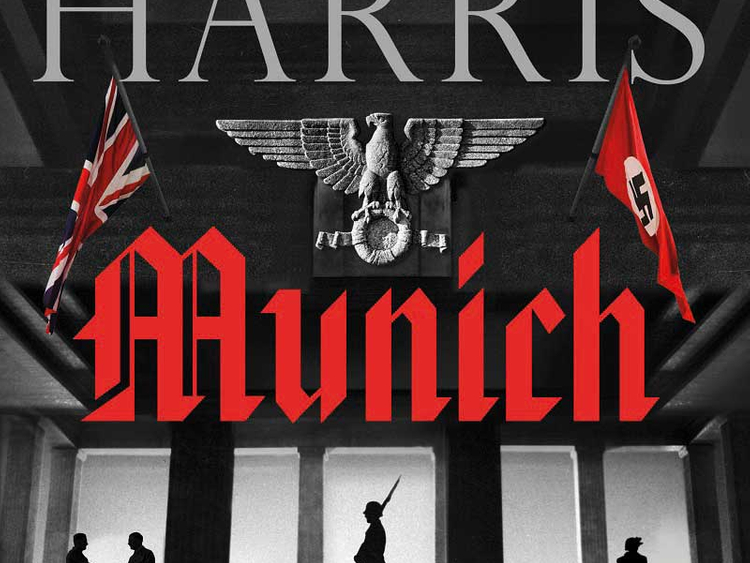

By Robert Harris, Hutchinson, 320 pages, $25

London, late September 1938. Slit trenches are being dug in Green Park and at home children are fitted with gas masks. Hitler is determined to invade Czechoslovakia in his scheme to reclaim lost German territory. Chamberlain is equally determined to prevent another war. Europe holds its breath as a last chance for peace goes up for grabs at a conference in Munich.

As history this feels so well known as to defy a further rehearsal. Chamberlain’s piece of paper has become as pathetic in its way as Desdemona’s handkerchief: a white flag in the face of oncoming tragedy. As fiction, though, we’re just getting started.

Amid this febrile atmosphere Robert Harris has parachuted one of his trusty old-school protagonists through the interstices of historical events, sticking tight to the record but suggesting how things might have turned out differently.

Hugh Legat, late of the Foreign Office, now a private secretary to the PM, is privy to the “real truth” about Britain’s home air defence. The RAF has only 20 fighter planes “with working guns” to defend the entire country, so a war would be not only morally repugnant but strategically disastrous. Legat, a brilliant Balliol scholar, is also an upright, downright, forthright stiff, perhaps deliberately: Harris doesn’t want a “colourful” lead stealing any of the narrative’s thunder.

Meanwhile, in Berlin, a high-born diplomat named Paul Hartmann has joined a group of conspirators plotting against Hitler. Hartmann has got hold of a document outlining Germany’s expansionist ambitions, including their intention to launch a surprise attack and “smash” the Czechs.

If the plotters can somehow convey this dynamite to a sympathetic ear in Whitehall it might provoke the British government to take action, and stop “the madman” in his tracks. The first hundred or so pages of Munich are full of tight little huddles, grave-faced men darting in and out of offices.

At times the documentarist in Harris seems to be rather crowding out the novelist, hugging the shore of verifiable fact instead of boldly striking out on the choppier waters of fiction. I’m not sure, for instance, of our need to know that the Fuhrer’s train south to Munich went “at an average speed of 55 kilometres per hour”. But then a couple of pages later Hartmann, aboard the train as an assistant translator, visits the toilet and notes the tiny steel swastikas adorning the taps — the vigilant novelist has reasserted himself. “No escaping the Fuhrer’s aesthetic, thought Hartmann, even when one took a shit.”

After the pianissimo first section the book turns up the volume as the dual plotlines converge: Hartmann, who was a friend of Legat’s at Balliol, is relieved to discover that the Englishman is also on his way to Munich, aboard the PM’s plane.

Both men must operate under a lowering cloud of suspicion as they inch closer to the respective centres of power, revealed to us in telling pen portraits. Chamberlain, nearing 70, a Victorian throw-back in stiff wing-collars, constantly surprises his staff with his energy and his “ostentatiously modest” way with the spotlight.

Hitler, impatient and dour, presents a more enigmatic figure: how did this unexceptional man (“it was almost compelling how nondescript he was”, thinks Legat) bewitch a mighty nation into surrender? And just for good measure Harris throws in this sulphurous firecracker: he has the body odour of “a workman who had not bathed or changed his shirt in a week”. On top of everything else, Hitler stank.

As the negotiations grind on the scene is enlivened with touching squiggles of detail, such as the crowd outside the British delegation’s hotel striking up with “The Lambeth Walk” to make the visitors feel at home.

Munich itself comes to life in the poignant contrast between the gracious city of botanical gardens Hartmann once loved and the new brutalist parade-ground spiked with gigantic flagpoles and swastika banners. During a midnight flit outside Munich he gives Legat a terrible glimpse of where Nazi Germany is heading, and both men come to a private reckoning of their failure to make a mark. A tense encounter in Hitler’s apartment is the book’s thwarted climax.

A tantalising addition to the inexhaustible game of “what if?”, Munich is one of Robert Harris’s more contained performances, less daring than Fatherland , not as compulsive as Pompeii , his best novel. The story of a crisis averted is, perforce, something of a pulled punch. But it makes for an ominous foreshadowing of the main event. “Our enemies are small worms,” the Fuhrer would tell his generals in August 1939. “I saw them in Munich.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Anthony Quinn’s latest novel is Eureka (Cape).