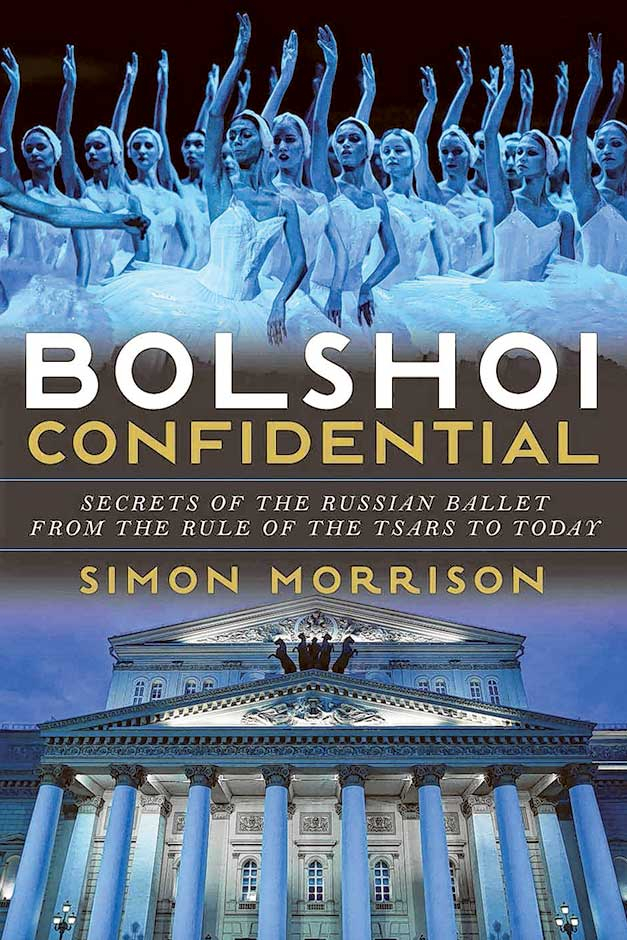

Bolshoi Confidential: Secrets of the Russian Ballet from the Rule of the Tsars to Today

By Simon Morrison, Liveright, 512 pages, $35

This massive survey of the 240-year history of Russia’s most famous theatre begins on the night of January 17, 2013, when Sergei Filin, artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, had acid thrown in his face. The crime, instigated by a member of the company whose ballerina girlfriend had been denied promotion, left Filin half-blind and the Bolshoi’s reputation in tatters. How could an institution that existed to celebrate beauty and exalted emotion be riven by such anger, jealousy and violence?

Quite easily, suggests Simon Morrison, Princeton professor of music. “Rather than an awful aberration, the attack had precedents of sorts in the Bolshoi’s rich and complicated past,” he writes. “That past is one of remarkable achievements interrupted, and even fuelled, by periodic bouts of madness.”

Indeed, the assault on Filin pales alongside the treatment meted out to a forgotten teenage ballerina, Avdotya Arshinina, who on January 5, 1847, was “dumped at the door of a hospital experiencing ‘fits of madness’ and ‘constant delirium’. Pale and emaciated, she had severe injuries on her head and body as well as bruised, infected, ‘blackened’ genitalia.” She died of her injuries 13 days later.

The subsequent investigation revealed that, with the collusion of her father, she had been drugged and gang-raped at a party thrown by Prince Boris Cherkassky. The aristocrat, inevitably, escaped punishment; her father was sent to Siberia for two years. The case revealed, Morrison notes, “a wretched economy where lesser-skilled dancers were promised access, through their art, to aristocratic circles, only to become sex slaves”.

This history is peppered with shocking incidents of sex, violence and cruelty. Morrison chronicles the dead cat thrown at the feet of Elena Andreyanova by a supporter of her rival, Ekaterina Sankovskaya, in 1847 and the appalling double suicide in 1928 of two dancers who plunged to their deaths “from the uppermost flies of the stage in full view of the public” for love of the designer Mikhail Kurilko. The ballerina Ekaterina Geltser — saviour of Russian ballet, according to no less an authority than Konstantin Stanislavski — was at the time performing “The Red Poppy”, an early and popular example of Soviet propaganda where brave workers side with the oppressed Chinese against the fiendish British.

Morrison’s contention is that such incidents of individual drama are part of a theatrical culture intimately entwined with the nation’s politics and mores. “In Russia, politics can be theatre, and theatre politics,” he argues.

The connection was there from the very beginning, when in 1780 the Englishman Michael Maddox — “either a mathematician or a tightrope walker during his youth” — ended up with a licence from Catherine the Great to run a theatre (the first of three that have stood on more or less the same site in Moscow). His money troubles meant that the place quickly became reliant on imperial support, and the proprietorial interest this triggered among Russia’s rulers continued through the tsars, into the Soviet era and up to the present day.

The February revolution in 1917 caused surprisingly little disruption — the rehearsal schedule simply announced “no rehearsal on account of revolution” and a performance was suspended. But after October, when the Bolsheviks seized full control, the ideological problems of ballet itself were a cause for much soul-searching. The Bolshoi may have been the scene for the declaration of the Soviet Union — in December 1922, it hosted the political congress that voted the USSR into being — but the ballet performances on its stages represented a real challenge to revolutionary values.

In the crisis of 1918-19, the hardline Moscow commissar Vladimir Galkin asked: “Are we still of the mind to keep allowing precious fuel to be thrown into the voracious furnaces of the Moscow state theatres, tickling the nerves of diamond-clad baronesses, while depriving heating stoves of the wood that could save hundreds of labourers from illness and death?”

It was Lenin himself who answered him. “It seems that comrade Galkin has a somewhat naive conception of the theatre’s role and significance. We need it less for propaganda than to give rest to our workers at the end of the day. And it’s too early yet to put the bourgeois artistic heritage in an archive.”

So the Bolshoi survived, becoming under Stalin a key tool in the propaganda war, where ballet had to represent heroic workers, not fairytale princes, and each commission was subject to censorship from Glavrepertkom, a board that controlled every aspect of every performance, with stultifying and dangerous consequences.

Morrison charts the effects on composers such as Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Khachaturian in minute detail. In a lengthy chapter on the ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, whose father was shot and mother imprisoned during one of Stalin’s purges, he recounts how even in the years of the “thaw” she had to write grovelling letters to Khrushchev apologising for not respecting the KGB surveillance to which she was subject, in order to be allowed to travel abroad.

“In the last few years I have behaved unspeakably badly without realising the responsibility that rests on me as an actress with the Bolshoi theatre,” she wrote, listing the crime of talking to foreigners without permission among her many sins.

Ironically, given her pursuit of artistic and intellectual freedom, it was Plisetskaya’s performance of “Swan Lake” that was played on an endless loop on Soviet TV during the ill-fated coup against Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991 — a symbol, if one were needed, of the ties between the Bolshoi Ballet and the state that Morrison devotes some 500 pages to describing.

Yet for all its forensic detail and fascinating facts, this is a flawed undertaking. It has a confusing tendency to double back on itself in terms of chronology, as if the detail has overwhelmed the writer. He loses his thread in the labyrinths he is exploring. Characters appear so briefly you lose track of who’s who. More crucially, Morrison is a music specialist, a fact that is reflected in lengthy, revealing but not always pertinent discursions on composers who provided scores for the ballet.

What he isn’t — judging by this book — is a ballet-lover: “Bolshoi Confidential” lacks any sense of the company’s artistic merit. “More is known about the scandals than the glories of the Moscow stage,” Morrison admits, “because the scandals generated heaps of documents. The glories ... inspired nothing more specific than poetic tributes, bouquets of words.” But this approach skews the narrative.

Morrison writes confidently about the Bolshoi’s muscular, dramatic style, but he displays little understanding of the contribution made by individual dancers to the company’s history. He can describe backstage intrigue, and the way audiences of the 1960s used to charge upstairs at the interval before the food in the top-floor canteen ran out, but not the way that Irek Mukhamedov made Yuri Grigorovich’s unwieldy “The Golden Age” flare to sudden life, or the impact Galina Ulanova had on audiences when she came to Moscow from St Petersburg, or why Plisetskaya was adored not just by the Politburo but by an entire generation of dance lovers.

It is what unfolds on stage that makes the Bolshoi matter. This is a fascinating glimpse behind the scenes, but it pays too little attention to what happens when the curtain rises.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd