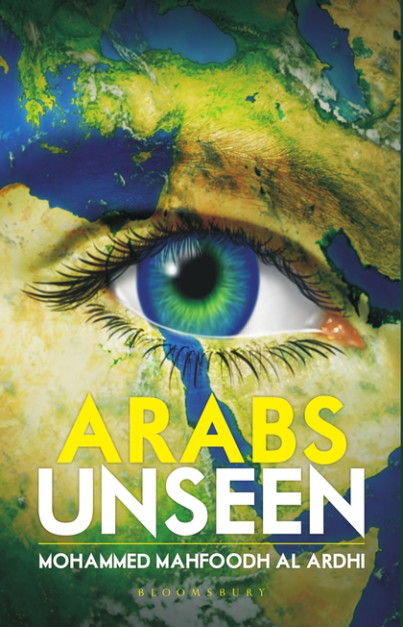

Arabs Unseen

By Mohammed Mahfoodh Al Ardhi, Bloomsbury India, 142 pages, £13

The Arab world has an unprecedented window of opportunity to invest in its young people before the millions of children growing up in the region overwhelm the system. Social optimism in the Arab world is far too rare and is something that should be cherished, which is why Mohammed Mahfoodh Al Ardhi’s book “Arabs Unseen” is such a satisfying jolt to the system.

He is deeply concerned that unemployment is undermining the accumulation of human capital that is the main force for propelling growth in the Arab world. He is well aware that the challenge should not be underestimated as we continually read grim analyses of the Arab world’s problem of 220 million people under the age of 30, and the region’s high rate of unemployment — at an average of 10 per cent, of which young people take a disproportionately high share. The lack of opportunity translates directly into social disaffection, and the unrest that has gripped the region since the Arab Spring.

Nonetheless, the encouraging thing about “Arabs Unseen” is that Al Ardhi refuses to accept this situation as a given, and is committed to changing what he calls “the gloomy master narrative of the Arab world”, based on the absence of state authority, extremism, with a debilitating focus on strife and suffering. Al Ardhi has a lot of experience in working with young Arabs and he speaks with a very clear counternarrative based on his experience as a significant leader in the Gulf’s business community, chairing both Investcorp and the National Bank of Oman, and previously having been the Chief of the Omani Air Force.

Al Ardhi wants to challenge overwhelming gloom by showing what can be done in real life. He eschews the glib language of the management consultant and avoids the hopelessly long words of the sociologist. Instead, he uses clear and simple storytelling to profile 10 examples of young Arabs who have made a difference through their work, or by founding companies or institutions that have taken their efforts beyond their immediate environs to the wider Arab world, and inspired some kind of optimistic change. He wants to spread the word of these people’s work as examples of “the good that comes from this work, the positive social impact that at once fuels their ambition and sets them apart, making the ‘stars’ that they are today”.

It is also important that this very successful businessman identifies so closely with these young social changemakers. Al Ardhi notes that as a young man growing up in pre-modern Oman and enduring all the deprivations of that time, he also knew the pressure of struggling to improve oneself. And then as a young fighter pilot he knew the importance of acting quickly and decisively, executing plans and learning to lead. He is right to draw a close parallel between his own tale and the very different stories of the 10 social young people who also shared a lot in common: they all confronted similar challenges, harboured the same fears and struggled with doubts. But they all had their own visions and a passion for their work that saw them through and enabled them to find success.

For example, he tells the story of Lotfi Maktouf, who started from very humble origins in Tunisia and got to Harvard Law School, and on to a lucrative job in Wall Street. Rather than seeking comfortable retirement, Maktouf set up Almadanya, a non-political philanthropic organisation that targets the root cause of unrest in Tunisia, which is the underrepresentation of youth in the country’s economy and the disenfranchisement of large segments of the population, working with the aspiration that “to begin work today will allow our youth to have a better tomorrow”.

Another example Al Ardhi gives is the Emirati animator Mohammad Saeed Hareb, whose success started from the most unlikely point of a grim report card from Northeastern University in Boston flunking him from his first class in architecture and kicking him out of the course. Forced to switch majors, he resisted pressure to do something more practical and chose General Arts, which required him to take a course in animation. He says that it was in that class that he first sketched Um Saeed, the key character in what would become the Middle East’s first 3D-animated TV series, the wildly popular “Freej”.

These two cases represent the 10 that Al Ardhi has chosen to as leading examples of young Arabs who were determined to make a difference. Along with the others in this fascinating series of profiles, Al Ardhi sees them as “representing hope in our collective future: men and women who have cut their own paths, and how sheer tenacity and force of will have turned their dreams into reality. They are living proof that amid the maelstrom of violence and chaos engulfing much of the region, positive change is coming.”

Al Ardhi uses his book a passionate appeal to improve the quality of education in the Arab world. Clearly, none of the individuals in the book would be where they are today without working hard to excel. But they also needed good education to make it happen, and Al Ardhi, throughout the book, emphasises that it is a key starting point for the next generation of young Arabs to realise their full potential.