The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1966-1989

Edited by George Craig, Martha Dow Fehsenfeld, Dan Gunn and Lois More Overbeck, Cambridge University Press, 942 pages, $50

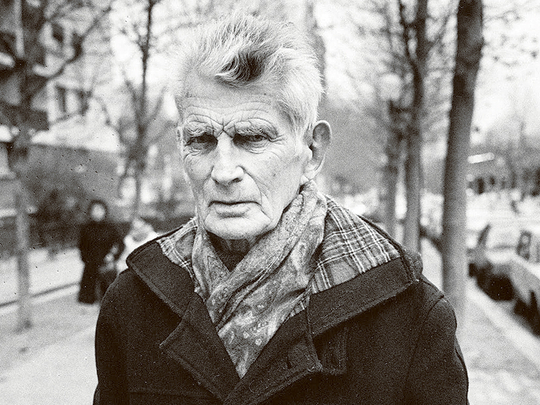

In his life, his work and his letters, Samuel Beckett seems from the start to have aspired to, indeed to have yearned for, decrepitude and its inevitable consequence, oblivion. His most desperate and loveliest lines are given to those at the end of their tether — literally so, in the case of Lucky in “Waiting for Godot” — to the last-gaspers, the winded stragglers in the human race. His profound disaffection, which in any other would have seemed self-pitying and self-indulgent, lies at the foundation of a negative aesthetic which sustained him in his creativity to the very end.

If “A Piece of Monologue” (1979) opens with the line “Birth was the death of him”, a mordantly witty variation on a phrase much favoured by the Irish, his last piece of published writing begins and ends with the urgent question he had been posing to himself from the beginning: “what is the word”.

“The Letters of Samuel Beckett: 1966-1989”, the last of four fat volumes, is inevitably a matter of dwindlings. On not a few of these pages the annotations, even in a minuscule typeface, are far more substantial than the primary text, and in some cases come close to swamping it entirely. This is the case not just towards the close of the volume, which marks also the close of Beckett’s life, but even in the mid-1960s when he was still hale, if not hearty, which, if we are to credit his own accounts, he never was.

It is worthwhile, at this final stage, to glance back at the history of the publication of the letters — the partial publication, that is, since only a fraction of the many thousands he wrote during his lifetime are contained in the four volumes. It has been an immense undertaking, involving not only the editors but scores of student interns at the American University of Paris. As is well known by now, Beckett for a long time refused to sanction the public airing of his correspondence, and when in the end he relented, he did so with the stipulation that publication should be posthumous, and confined to those letters that had a bearing on his work.

In 1985 he appointed his American publisher at Grove Press, Barney Rosset, as general editor, the actor and critic Martha Fehsenfeld as editor, and Lois More Overbeck as associate editor. After the first volume was published, the French translator George Craig and Dan Gunn, a professor at the American University in Paris, joined the editorial board. In March 1983 Beckett wrote to Fehsenfeld: “I do have confidence in you & know I can rely on you to edit my correspondence in the sense agreed with Barney [Rosset], ie its reduction to those passages only having bearing on my work.”

The wording here is extremely significant, and much of the subsequent debate about the validity or otherwise of the entire project has focused upon it. It seems clear, if anything in this matter may be said to be clear, that Beckett envisaged a slim volume of extracts from his correspondence that would have to do solely and directly with the technical aspects of his published novels, drama and poetry.

Presumably he felt confident that in making such a stipulation, his privacy as man and as artist would be secured and well guarded against the prurient eyes of his readers, and the professional hunger of scholars. If this was his belief, it was not soundly based.

It is true that Beckett, certainly after he had achieved fame through the worldwide success of “Waiting for Godot”, refused with unrelenting stoniness to offer even the smallest crumb of enlightenment to anyone foolhardy enough to inquire as to the sources for and the meaning of his work, claiming flatly to have no knowledge of such things himself. But in allowing the publication of those of his letters “bearing on my work”, he seems to have forgotten the extensive and fevered screeds he wrote to the French critic Georges Duthuit in the late 1940s and the early 1950s — at the time when he was composing the novels that make up the so-called Trilogy: “Molloy”, “Malone Dies” and “The Unnamable” — in which he is not so much addressing Duthuit as communing urgently with his own artistic consciousness.

There was also the extraordinary letter he wrote, in German, to the editor and critic Axel Kaun in July 1937 in which he set out, with unheralded and never-to-be-repeated directness, his conviction as to what art should be, and what he intended that his own art would be, that is, a “literature of the non-word”. It was to be hoped, he wrote, that “the time will come, thank God, in some circles it already has, when language is best used where it is most efficiently abused. Since we cannot dismiss it all at once, at least we do not want to leave anything undone that may contribute to its disrepute. To drill one hole after another into it until that which lurks behind, be it something or nothing, starts seeping through — I cannot imagine a higher goal for today’s writer.”

It seems unlikely that, had he bethought himself, Beckett would have countenanced the publication of such passionate, and such revealing, outbursts. Far more serious, according to some critics, was the latitude that Fehsenfeld and her fellow editors allowed themselves in the interpretation of Beckett’s wishes when he agreed to the publication of “those passages only having bearing on my work”.

The strategy that the editorial quadrumvirate adopted was to publish not just “passages” relevant to the work, but entire letters in which such passages occurred. The result is that, incidentally, as it were, we have learnt a very great deal more about Beckett’s life, loves, family relations, heart palpitations, cysts, hammer toes and anal pruritus than this most private of men would ever have imagined we should. As he wrote to his biographer, Deirdre Bair — he called her book “the Bair fantasy”, though he claimed not to have read it — “My relations with people are nobody’s business.” Nor, surely, is his itching bum.

Here, of course, arises the question of how much privacy an artist is to be afforded, especially after he is dead. Many biographers and editors are firmly of the belief that everything it is possible to know should be known. Consider the controversy over the publication of Joyce’s erotic letters to his wife, Nora. Should they have been published? And when they were published, did they enhance our understanding of his work, or simply reveal that he had, like everyone else, a dirty mind?

Another fundamental example of wilful frankness on the part of a biographer is Humphrey Carpenter’s life of W.H. Auden, which missed no opportunity to keep readers informed on the comings and goings of the poet’s rectal fistulas.

And yet, if we were given the choice, would we be without these four detailed and lovingly edited selections of Beckett’s letters, even if they are only a small selection? Of the four volumes, the second is probably the most compelling, and the most telling, covering as it does the writing of the three great novels of the Trilogy, and Beckett’s first ventures into the theatre, which were to result in such excesses of unexpected and unsettling success, fame and fortune.

Yet Volume IV, despite an inevitable, general lessening, has its many moments of illumination, indeed of splendour, even as the light of Beckett’s life and work dims. As the anonymous author of the beautifully written and, in places, deeply moving General Introduction has it, in this last phase “the line between work and life, never clear, becomes less and less discernible” as the artist, facing up to his own death, “hopes, in fading from the world, finally to be able to write a consummately fading work about fading”.

As always with Beckett, of course, laughter, however bleak, will keep breaking through. His wordplay becomes, if anything, more ingenious and mordantly funny the older he gets. To a request to be interviewed, he replies: “I have no views to inter.”

On December 31, 1983, to the editor of “The Times” in response to questions for a New Year feature, he dispatches this wonderfully baleful telegram: “RESOLUTIONS COLON ZERO STOP PERIOD HOPES COLON ZERO STOP BECKETT.” Writing in his 80s to one of the friends of his youth, Mary Manning, he observes ruefully that, “It’s wholly ghost I’ll soon be.”

In this volume we are also offered repeated instances of Beckett’s unfailing kindness and generosity. Envelopes addressed to various family members and friends, and even some strangers, will have unsolicited cheques slipped into them, while in a letter to his publisher, Jerome Lindon, in 1969, after he had been awarded that year’s Nobel Prize, he reveals a plan not only to donate the prize money to the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, but “to dis-honour myself still more by devoting (on the quiet, and in stages) an equivalent amount drawn from my ‘gains’ to the alleviation of personal misfortunes”.

Striking, too, is the continuing affection he displays towards old friends and, especially, former lovers — although his wife, Suzanne, remains the strangely shadowy, liminal figure that she is in all the letters — or all of them, at least, that we have been allowed to read. When shall we have a biography of that remarkable woman?

Whatever cavils may be adduced against “The Letters of Samuel Beckett”, it would be churlish and ungrateful, here at the end, not to acknowledge the dedication, hard work and love that have gone into the making of this splendid monument to a great artist.

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2016

John Banville’s “Time Pieces: a Dublin Memoir” was published last month by Hachette.