4 3 2 1: A Novel |

By Paul Auster, Henry Holt and Co, 880 pages, $20 |

The last thing you’d expect Paul Auster to write is a social-realist novel of panoramic, Dickensian scope. He’s known for his concision, his affiliations with European modernism, his conjuring tricks and sleight of hand. But there’s a telling tribute to David Copperfield halfway through this book, along with a rebuke to Salinger’s Holden Caulfield for badmouthing Dickens in the first sentence of The Catcher in the Rye. More to the point, the opening of the novel — Auster’s first in seven years — is engagingly old-fashioned in spirit, as the genealogy and childhood of one Archibald Isaac Ferguson are set out.

Surely it can’t be that simple? And no, it isn’t. Ferguson, it emerges, isn’t the hero of his own life but of his own lives, plural. With 800 pages still to go, any illusion of a single narrative begins to crack. What’s this reference to Aunt Mildred never having married when we’ve just been told the name of her husband? How could Uncle Lew have both made a fortune from and been bankrupted by a bet on the 1954 baseball World Series? Which to believe: that the warehouse on which the family business depends was burgled or that it burned down?

Even those who are taken in at the start will quickly clock the narrative logic. From his one beginning, as the only child of Stanley and Rose Ferguson, born (as Auster was) in 1947, the hero quadruples. His four selves go their separate ways, each with his own experience of childhood, adolescence, friendship, love, sport and school. His parents likewise have fourfold lives, while retaining their names and professions (he’s a businessman, she a photographer). So too, key figures in Ferguson’s life, notably his cousin/girlfriend Amy, assume different roles and characteristics.

For all the novel’s structural complexity, the premise is simple. The film Sliding Doors might be one analogy.

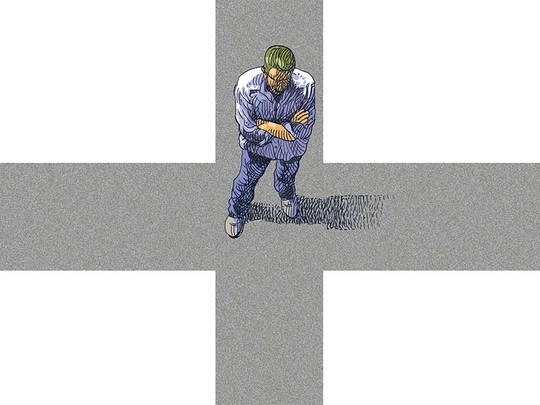

The rationale is made explicit in the closing pages, as the fourth Ferguson — F4, as it were, who by this point is in his 20s — reflects that “the torment of being alive in a single body was that at any given moment you had to be on one road only, even though you could have been on another, travelling towards an altogether different place”. Only imagination (or cloning) can circumvent these limits. Hence this novel about “four identical but different people with the same name Ferguson”.

Though there are echoes of Auster’s life throughout the text, the sheer weight of historical detail acts as a defence against solipsism. The Cold War, the execution of the Rosenbergs, JFK, Martin Luther King, the Vietnam draft, the My Lai massacre, the Kent State shootings: here’s a novel as attentive to period detail as Philip Roth would be, or Richard Ford, or Jonathan Franzen. The new expansiveness is reflected in the sentences, which run on, fluent, self-delighting, reluctant to stop. And the relationship between the private and public is neatly evoked through the image of concentric circles, with the world (and war) on the outer rim and the individual (and his battles) a small dot at the centre. Auden and Isherwood once wrote a play called The Ascent of F6. Auster’s novel might have been called The Descent to F4, though the title he settled on, with its descending numbers, is equally apt. It’s not a case of And Then There Were None, but given the turbulence of the period, and various catastrophes described (conflagrations, car crashes, brawls), a heavy death toll is unsurprising. Auster’s perception of life’s frailty has roots in his own experience. As a teenager at summer camp, he saw the boy next to him killed by lightning during an electric storm. He offers a variant here, when a boy with a similar name to Ferguson’s — Artie Federman — dies of a brain aneurysm. The multiple selves are involved in multiple dramas. There was a time when Auster seemed to regard narrative momentum as an offence to the duties of meta-fiction. That’s not the case here. The reader is urged to go with the flow.

Once you stop and come away from the novel it’s hard to remember which Ferguson it was — 1, 2, 3 or 4? — who broke his arm falling out of a tree, lost two fingers in a car accident, launched his own newspaper while still at school, first had sex on the same day that JFK was assassinated, visited a prostitute called Julia, was seduced by a gay student called Andy, got stuck in a lift during a power cut, or walked in on his grandfather making a porn film. Does it matter? Not much. While reading, you’re immersed. But it’s hard to suppress a sense of missed opportunity. If Auster was going to invent four different lives, why make them so similar? Why the recurrent obsession with sport (baseball and basketball), movies and Paris? And the same pursuit of a writing career? Why not send his hero somewhere else entirely, whether China or a car production line? It’s not that Auster can’t think outside his own box (the sympathy with which he draws the minor characters proves he can) but that for him DNA seems to be destiny. Nature triumphs over nurture. Rich or poor, straight or gay, urban or suburban, the Fergusons share more than divides them. The four merge back into one.

Thanks to the numbered sections, their narratives could, at a pinch, be read separately, one after the other. An arrangement of differently coloured Post-it notes (or, more brutally still, a cut-up of the pages) would make it easier still, with four shortish novels replacing one of 900 pages. But what would be lost is the sense of moving through time — and of seeing the Fergusons grow up alongside each other. The interweavings and disjunctions are part of the fun. When one F is having it rough (“The best thing about being 15 is that you don’t have to be 15 for more than a year”), another is coming into his own. When one chooses AI Ferguson as his pen name, another opts for Isaac Ferguson. And so on.

The novel drags towards the end. The recounting of student protests at Columbia is disproportionately long. There’s too much propagandising on behalf of writing (as “the difference between being alive and not alive”) rather than allowing the writing itself do the work. And a novel that opens so expansively ends in narrow self-referentialism as F4 decides to “invent three other versions of himself and tell their stories along with his own story”, a project he embarks on after moving to Paris in 1970 and which he completes five years later, with a novel of 1,133 pages.

An earlier glance into his future suggests the novel will prove unpublishable. Auster’s version, 42 years on, has the advantage of a lifetime’s practice and the conviction that this, more than any other, is the book he always wanted to write. A work that begins with the story of an east European immigrant (Ferguson’s grandfather) arriving at Ellis Island on the first day of the 20th century has the right credentials for a great American novel. But the story is jokey and unreliable, and Auster is too wedded to his own experience to pretend that it’s everyman’s. It’s enough to have produced a novel that celebrates the liberal values of his generation — from love of art to concern for justice — at a time when they’re under siege. Ferguson may be stuck in a bubble. But better a bubble than a wall.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Blake Morrison’s Shingle Street is published by Chatto.