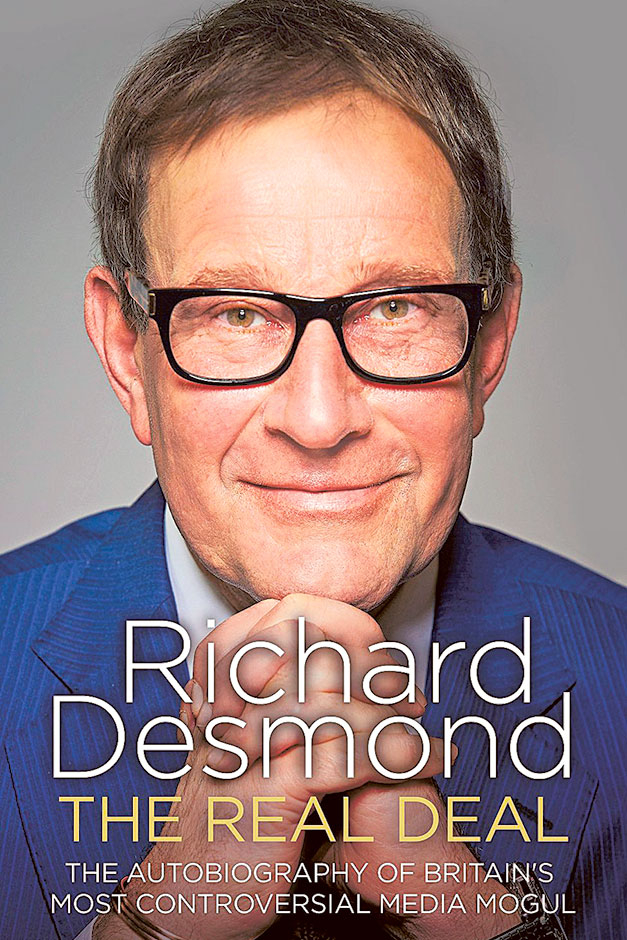

The Real Deal: The Autobiography of Britain’s Most Controversial Media Mogul

By Richard Desmond, Random House UK, 352 pages, $35

The conventional wisdom among most of the candidates who want to succeed Ed Miliband as Labour leader is that he just wasn’t business-friendly enough. What can that phrase mean? Even the candidates themselves seem hard-pressed to know how friendly the party needed to be and to what kind of business. Are there to be limits? Blairite precedent suggests not, especially when the business is the media.

Let the witness here be Richard Desmond, who by November 2000 had made enough money from specialist periodicals, seedy publications and “OK!” magazine to buy Express Newspapers for £125 million (Dh715.5 million); or, to be more exact, enough assets to secure a loan from Commerzbank in Frankfurt that enabled the purchase.

Moments after he walked into the Express building for the first time as its owner, he took a call from Tony Blair inviting him to come to Downing Street that evening “to celebrate”. Desmond demurred — he wanted to meet his staff — but went round the following night to find Blair “very relaxed, very hospitable and very charming”.

Desmond, who thought of himself as a Tory, found himself disarmed by a prime minister who could chat about rock and pop music of an earlier period, when Blair was a student guitarist and Desmond an aspiring young drummer. He was also flattered by Blair’s keen interest in his seedy magazines.

Then, as he was leaving, Blair put the question: which party did he think he (meaning his newspapers) would support in the next general election. Desmond replied that he hadn’t thought about it. So far as he was concerned, he said, “you’re all [expletive] mad. I mean, who would do this [the prime minister’s] job for a hundred grand a year and a free rundown house?”

But quite soon he did think about it when the Labour Party asked him for a contribution to the party and Desmond, who was short of ready cash, suggested £100,000 worth of free advertising in the “Daily Express” instead. The negotiation that followed involved Alastair Campbell, who used to write for Desmond’s “Forum” magazine.

Like most other deals described in the book, Desmond came out on top. He gave Labour £100,000 and later charged the party for the six pages of advertising that he’d originally offered for free. The bill came to £105,000. An act of apparent philanthropy had made him £5,000. (A few years later he confessed the truth of this to Gordon Brown, who could say only “tut, tut, tut”.)

Still, when the 2001 election came around, the Express papers supported Labour. Desmond might well have been ennobled in return — he thinks Blair “would have liked to recognise my achievement” — had it not been for his first wife, Janet, who, when asked by Tony and Cherie how she would like being Lady Desmond, said that she and Richard “didn’t hold with all that kind of thing”.

In this and other events, the trustworthiness of the account is hard to measure — dialogue so immaculately remembered is often invented. This book was ghostwritten by Martin Townsend, the former editor of “OK!” who now edits the “Sunday Express”.

But it contains enough self-disclosure of poor behaviour and sharp practice to give an impression of candour, even though Desmond has omitted one or two of the more notable incidents that helped to establish his reputation as a foul-mouthed bully, such as the out-of-court settlement, said to be in six figures, that was awarded to the newspaper executive who alleged Desmond had punched him.

“I have a strong suspicion that a third of my readers will like me and my story, a third will hate me and a third won’t care at all,” he writes in the introduction. Despite Townsend’s spit-and-polish on the anecdotes, however, it seems unlikely that Desmond will ever manage to endear himself much beyond the outskirts of his family.

And yet his story is not unsympathetic. Born into a prosperous Jewish family in north London, his comfortable childhood vanished when his father, who had a successful career as a senior executive with the cinema advertising agency Pearl & Dean, turned stone deaf and gambled away his savings.

Aged 13, he earned his first money running a cloakroom at jazz nights in pubs. Aged 15, he abandoned his drumming ambition and landed a job selling advertising for weeklies such as “Construction News” and “Hotel & Catering Times”, where he “turned out to be a bit of a superstar at telesales”.

Aged 18, he was earning £3,000 a year and another £3,000 in commission, which in 1970 amounted to about double the income of an average Fleet Street journalist.

Selling rather than journalism is what interests him — he compliments Blair by describing him as one of the best salesmen he has ever met. Clearly, he isn’t a fool. He bought Channel 5 for £103 million in 2010 and sold it for £450 million four years later. He may even have liberal instincts. He founded magazines devoted to the environment and alternative lifestyles, and eventually saw the latter make money.

It was ludicrous of him to tell David Beckham and Posh Spice that he was going to make them “the new king and queen of Britain”, but clever of him to have spent £1 million on exclusive rights to the Beckhams’ wedding, which sold 6 million copies of “OK!” at £2 each and for the first time pushed the magazine ahead of its rival and inspiration “Hello!”.

The Express group presented a different challenge. By 2000, the starry Beaverbrook years were long gone and the circulation was in steep decline — it was hard to see how the papers could be reinvented to capture new markets in what turned out to be the newspaper industry’s last fling.

But with ruthless cost cutting, Desmond has wrung a profit from his shrinking assets. Rather than trying to build sales, he has simply accepted that his papers are on their way out and that, in the medium term, the road to profit lies in them surrendering to their fate.

So no circulation stunts, no giveaways, no increased coverage of this or that: the Desmond recipe for success at the Express is to reinforce its ageing readers’ opinions, and give them occasional hope of increased mobility and pain relief with frequent front-page splashes that promise cures for arthritis. “Affirmation rather than information” is his motto. And affirmation comes cheap.

The sun has almost set on the great age of British newspaper proprietors. Desmond is certainly not the most dangerous man in this lineage, or the maddest, but he may well turn out to be the most repellent. On the evidence of his memoir, I found it difficult to know whether his odiousness was a performance — his shtick — or whether, naturally rather than deliberately, he was simply odious.

Certainly he seems lonely. “I suppose when you are an outsider, you will always be an outsider,” he writes. There speaks a man who devoted several pages of his own newspaper to his own book launch party, to which not enough famous people turned up, and those that did made an excuse and left early. A cut-price “Citizen Kane”.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd