André Butzer describes himself as "the famous artist without ideas". "Paintings based on ideas are just illustrations, not art. I do not need ideas to go on with my work, because art is not about ideas or ideals. It is about striving to attain something you do not know and you cannot do," he says.

The German artist did not complete his art education because he was expelled from the Hamburg Art School after the first year. He then went on to establish the Academie Isotrope, an independent art school run by a group of artists, and served as the editor of Isotrope magazine. He is well known for his vibrant, witty paintings that combine pop culture and art history, and the philosophical concept of a fictional unattainable place called Nasaheim to comment on contemporary society.

Butzer's bright, textured paintings feature cartoon characters, junk food and other images from popular culture. But the compositions are inspired by the work of great masters. For instance, in Favourite Painting of Cezanne, the artist has presented many of Cezanne's famous works in his own unique vocabulary. And Entombment of Winnie the Pooh draws from Titian's famous religious painting to suggest the end of pop art.

An interesting feature of his work is his creative use of a specially mixed flesh colour seen in religious Renaissance art. In a painting titled Hearing Aid, he has used the colour to create the feeling of a living ear membrane on his canvas, inviting viewers to tune in to sounds beyond.

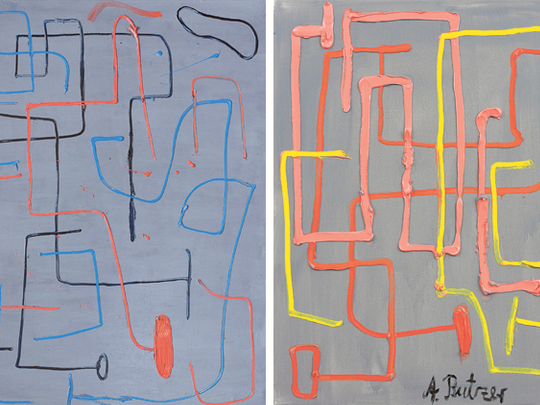

Butzer's mystical, symbolic concept of Nasaheim, or N, adds another dimension to his work and is what led to his style being described as "science fiction expressionism". But in the past few years his work has become more abstract and his palette more subdued.

His first exhibition in Dubai, organised in collaboration with Galerie Max Hetzler in Berlin, offers a retrospective of his work over the past decade. It includes his early Disney-inspired colourful paintings; several pencil drawings representing a transitional phase between figurative and abstract art; and his recent abstract works. We asked the artist about his journey, his concept of N and much more. And like his paintings, his answers were deceptively simple yet complex.

Excerpts:

You have said that ‘everything that is now is not interesting to me'. Why is that?

Because I believe in history, and history is about being in the past and the future but not in the present. I find the present difficult to deal with and hence not interesting for art. I prefer to go back or look forward. I believe in art as a historic model of the past and the future.

Why did you choose cartoon characters in your early works?

I am interested in the history of art and the works of artists such as Giotto, Titian, Cezanne, Rembrandt and Matisse. By using popular cartoon characters, I wanted to combine the history of art and that of mass media. An artist has to start with something figurative before he can move on to abstraction. So I chose the most recognisable images of our times and tried to possess them and make this famous cartoon brand my personal statement. As a play on the names of mass production pioneer Henry Ford and one of my favourite artists Henri Matisse, I called myself Henry Matisse. Gradually I moved from figurative to abstract art and sent these characters to abstraction — to N, where they disappear. I can't go back there and feel melancholic when I see these figures in my old paintings, because I cannot make them now.

Why did you use such vibrant colours and exaggerated textures in your early paintings?

Today we live in a world of virtual reality and I think painting is a medium that resists that. One part of my art is not visible, so I try to make the visible part as real, as tangible and as alive as possible.

Tell us about the flesh colour in your palette.

Renaissance artists used a blend of the three primary colours — blue, red and yellow — to create the look of flesh in religious paintings. I followed this old tradition and the flesh colour became the fourth primary colour in my palette to depict dead or living meat. But now I am getting rid of all colour and using one total colour, which is a fusion of silver, titanium, gold and platinum. The idea is to simplify by optimising my methods and realise my concepts to the maximum with a minimal look.

Please explain the concept of Nasaheim in your work?

The word is a combination of Nasa and Anaheim where Disneyland is located. Anaheim in California was originally a German settlement and this concept occurred to me when I went there in 2000. Initially I did not know what it was and tried to fill the concept with meaning. I said Nasaheim is a house on another planet where Matisse, Disney, Jackson Pollock and others live, or a place towards which paintings should travel but which we will never reach. But later I began to think of it as the philosophical or mathematical concept of a number N, which is a heavenly number or a cosmic law that is like a calculation for artists to find out where to put things in a painting so that the various parts of the composition can be related to the cosmic balances. In my paintings I often depict the N house as a symbol of this place. You cannot go inside because the house has no door. But it has two windows, through which you can see a projection of your own vision and maybe this is what Nasaheim is all about.

So what direction are your moving in now?

In German, hiking is a philosophical term, because we refer to the planets as hikers in heaven. So I am a hiker and I am getting closer to N — but I will never reach it. Beyond what is visible on my canvases is everything that you want to imagine. This has to do with N and is a projection that is connected to the canvas and to the cosmic laws. I began by tackling problematic issues such as genocide, socialism, consumerism and German and American history in my paintings, because you have to walk through these things before you can begin to get somewhere else. I am happy that I was able to explore these provocative topics in my work, and I realise that once you do this your art remains polluted by them. But now those images are gone and my task is to start cleaning and strive for work that is more pure and balanced.

How do you expect viewers to comprehend these concepts behind your paintings?

I do not expect anything. My art is very accessible and people can go wherever they want with it. People may love or hate my work but I am happy if it provokes them to think. I do not know if what I am saying is right but I feed myself with these concepts and need them for me to go on. For my first exhibition in Dubai I am displaying paintings from different stages of my career, because I want people to see that my art is not static, it is a work in progress but not yet realised.

What do you feel about your work being described as science fiction expressionism?

I like the science fiction part but I am not an expressionist. It was good to have been one but am proud not to be one any more.

You have said that the profession of art critic must be eradicated. Why?

I said this because I had had bad experiences with American critics, who think they are better than art itself. Their criticism hurt me but also made me stronger. But I believe art is not made for criticism, it is made to be embraced.

Jyoti Kalsi is a UAE-based art enthusiast.

The exhibition will run at Carbon 12 Gallery until April 20.