“Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy.” Martin Luther King’s voice crackles over the quiet gallery. “Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice.” When the young black artist Jean-Michel Basquiat rose to fame, two decades after that impassioned address, King’s dream was still far from a reality.

Subtitled “Now’s the Time”, Guggenheim Bilbao’s fine retrospective argues that the work of this pioneering painter, who tore through the white art world of 1980s New York with his barbed responses to injustice and police brutality, remains as relevant now as then, the recent deaths of Michael Brown, Freddie Gray and others having again shone a light on American race relations.

Basquiat’s star-studded life and early death from a drugs overdose in 1988, aged 27, have earned him a cult status, cemented by the huge prices his works fetch at auction. Born in Brooklyn to a Puerto Rican mother and a Haitian father, Basquiat had a middle-class upbringing full of books and museum visits.

He left home in 1978 a precocious teenager without a high-school diploma, but his poetic graffiti under the tag SAMO (“same old [expletive]”) caught the attention of SoHo residents. That he chose to inscribe his art on the walls of the gallery district indicates his ambitions.

Basquiat’s rise to fame was swift. He took part in the landmark “Times Square Show” and “New York/New Wave” exhibitions of 1980 and 1981, before selling out his first solo show at Annina Nosei the following year. He collaborated with Andy Warhol, DJed at fashionable clubs, partied with the likes of David Bowie and for a time dated Madonna.

But this show is, happily, light on biographical detail. Arranged thematically not chronologically, the focus is firmly on Basquiat’s artistic achievement. We get a sense of his development: he began painting scenes of urban life on to materials he found on the street, as in “Untitled” (1981), a cartoonish car spray-painted on foam, included in “New York/New Wave”, after which he could afford to work on canvas.

But Basquiat’s career does not follow a linear progression because he arrived, in a sense, fully formed. When Nosei met him, the dealer recalls: “He was particularly cultivated, even though he was [20]. He had read everything. He was way more sophisticated than all the others his age.”

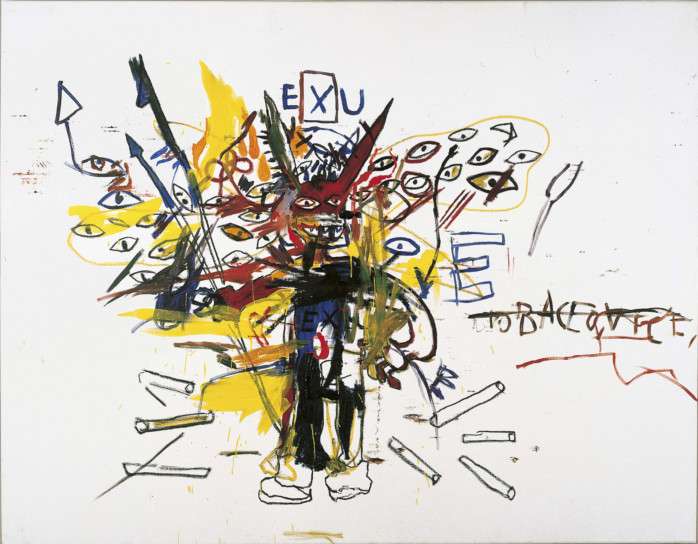

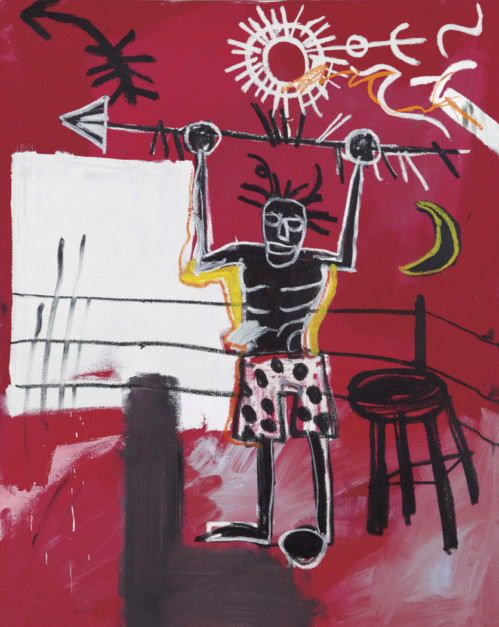

Basquiat once said that his subject matter was “royalty, heroism and the streets”. In his works black men are athletes and warriors, symbols of resistance and victory.

“Untitled” (1982) is a large, colourful, scratchy canvas depicting a masked boxer with a halo, or perhaps a crown of thorns. He is fresh from the fight, his headgear resembling a white gas mask. And though his crown suggests Christ, his arm is raised high: the stance of the victorious not the crucified. He is anonymous, a black everyman, but other works celebrate specific heroes — Jesse Owens, Charlie Parker, Cassius Clay — as if instating them in art history.

“The black person is the protagonist in most of my paintings,” Basquiat explained. “I realised that I didn’t see many paintings with black people in them.”

“The Death of Michael Stewart” is a tribute to the black graffiti artist beaten to death by the NYPD in 1983. Basquiat’s policemen are pointy-toothed cartoon villains wielding clubs and Stewart a black silhouette between them, a storm of red and blue raging around him. In a nearby self-portrait from the same year, Basquiat, too, becomes a silhouette — a nod to the 18th-century craze for such portraits, but with new political overtones. His identification with Stewart is clear: on hearing of his death, he said simply, “It could have been me.”

Basquiat uses colour with the sure instinct of a seasoned abstractionist, but it is never merely decorative. For him, colour is political. A photograph of “The Irony of a Negro Policeman” (1981) in the catalogue shows that Basquiat originally gave it an angry red background before painting over it in white, which is how it appears here, the red seeping through.

So often in Basquiat’s work, white is the colour of oppression, of “lesser” histories erased and obliterated. Here, black and white are anything but neutral.

The policeman is rendered ridiculous — as ridiculous as the paradoxical idea (to Basquiat) of a black policeman. He has the grotesquely simplified proportions of a child’s drawing, crowned with a wonky top hat. But such cack-handedness is, in fact, a studied affectation.

He treasured his childhood copy of “Gray’s Anatomy” and pored over Leonardo’s drawings. His cartoonish scribbles are not the result of a lack of skill, but rather they are a kind of visual shorthand — a riposte to the Modernist appropriation of “primitive” art.

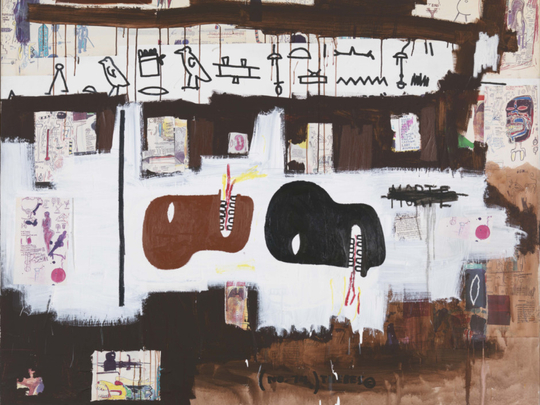

Symbols and words recur in his work: haloes, crowns, “MILK” (for whiteness), “SOAP” (whitewashing), “COTTON” (slavery). His obsessive crossing-out and overpainting can be read as a metaphor for the messy layering of history, for conquer and resistance. The resulting canvases brim with ideas and allusions. He often scratched into colourful, quick-drying acrylic with the end of his paintbrush, as much drawing as painting.

Borrowing from art history and everyday life, Basquiat was a true postmodernist. His lists recall the automatic writing of Surrealism, his appropriation of contemporary culture stems from Pop Art, while his gestural freedom and charged emotion is neo-expressionist.

Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time” plays in a room of the exhibition called “Sampling and Scratching”, and the reference to hip-hop is apt. Like a DJ, Basquiat mixed eclectic material — Beethoven, boxing, comics — to create something fresh.

In fact, his canvases are so littered with “samples” almost any of the works in the show could come under this category, and the selection sometimes feels arbitrary. But the curators are right to highlight his voracious consumption and cut-and-paste approach, which strikingly anticipate the internet era.

Basquiat’s visual signature was so well developed by the time he began collaborating with Warhol in 1984 that it is the younger artist who comes out on top. “Win $1,000,000” (1984) pits Warhol’s crisp silkscreen printing against Basquiat’s anarchic brushwork. While Warhol’s work is all about the clarity of the titular message, which is stamped across the canvas, Basquiat has mischievously blotted out his own line of text entirely. In “Ailing Ali in Fight of Life” from the same year, Basquiat pokes fun at Warhol’s neat Nike logo with a simple “CHEWING GUM TM”.

Warhol would begin each work and Basquiat would respond: again and again, the younger artist makes them his own — by turning a Warhol dollar sign into the anarchist snake symbol in “Don’t Tread on Me” (1985), for instance.

These paintings are more interesting for the artistic battle to which they play host than as works in their own right, and they received a critical drubbing at the time. But the critic who called Basquiat an “art-world mascot” was wrong: these pictures are a testament to his honed aesthetic and firm political convictions.

It is ironic that so many of Basquiat’s stridently anti-capitalist paintings now hang on the walls of private collectors, and it makes this exhibition a rare chance to see works not usually on public display. There are some omissions — including his early masterpiece “Untitled (Head)” from 1981 — but this is an engrossing look at an artist whose work resonates now as strongly as ever.

–Financial Times

“Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time” runs at Guggenheim, Bilbao, until November 1.