Despite the fact that almost six decades elapsed between 1952 and her death in 2011, most of the obituaries for the artist Helen Frankenthaler dwelt on the year 1952, as if this marked the sum of her achievements.

It was undeniably an important year. It is when Frankenthaler, aged 23, painted “Mountains and Sea” using a technique of her own invention that would pave the way for a new movement in art. She stained raw canvas with pigments that had been thinned out with turpentine so that pools of colour soaked directly into the fabric, rather than sitting on top.

Inspired by the abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock’s technique of pouring paint directly on to canvas laid on the floor, Frankenthaler had created a work that became “a bridge between Pollock and what was possible”, according to the artist Morris Louis. He saw “Mountains and Sea” while visiting Frankenthaler’s studio with fellow artist Kenneth Noland and the imperious critic Clement Greenberg, who was Frankenthaler’s lover at the time. (That the visit was undertaken in Frankenthaler’s absence speaks to the gendered hierarchy of the period). “Mountains and Sea” sparked the colour field movement, of which Frankenthaler, Noland and Morris were key protagonists.

Frankenthaler’s place in the art history books tends to stop here, largely ignoring her prolific output through the six decades that followed 1952. However, an exhibition that opened this month at the Gagosian gallery in Beverly Hills hopes to view her work through a broader lens. Entitled “Line into Color, Color into Line”, the show comprises 18 paintings created between 1962 and 1987.

“Art history gets written as a sequence of inventions. So, Helen is 1952 and less attention gets paid to what happened afterwards,” says John Elderfield, who has organised the exhibition. Elderfield was a friend of Frankenthaler’s, as well as the chief curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA in New York until his retirement (he is still curator emeritus).

This is his third Frankenthaler exhibition for the Gagosian. He hopes that it will lead to new readings of her work and demonstrate “that Helen continued to be an incredibly inventive artist. Some of the later pictures are just as extraordinary as the ones she was doing in the 1950s,” he says.

“Helen gets celebrated a lot as a painter of instinct, which she obviously is, but she’s also very calculating in what she does. The stress on the instinctive, while it’s absolutely there, is also a gendered reading of her work — this idea that women are instinctive and men are intelligent. Whereas in fact Helen was both — as all artists are, men and women,” he says.

Frankenthaler herself “didn’t want any discussion of her being a woman” or about her personal life (such as her marriage to Robert Motherwell), says Elderfield, who published one of the seminal books on the artist in 1989. “Things done in an artist’s lifetime involve a kind of compact with the artist about how it’s going to be done. The advantage is that you get to work closely with the artist, but there are certain things you won’t write about until after their death,” Elderfield says. “Helen didn’t really want discussion of her private life. She felt it had nothing to do with her work. Of course she was actually wrong — the work is not separate from the life. But she was of a generation where that’s what they wanted and that was the deal.”

The Gagosian exhibition focuses specifically on the relationship of drawing to painting in Frankenthaler’s work. “In the 1950s pictures there is a real sense of the hand and of a graphic impulse, which gets toned down a bit in the early 1960s but reappears soon thereafter,” Elderfield says. So, there are linear elements to the way pigment has been laid down in works such as “Pink Field” (1962) and “Parade” (1965), which resembles coloured icicles dripping from the roof of a cave.

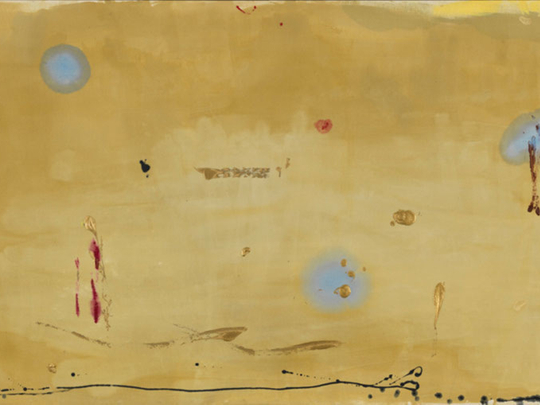

As she moves into the 1970s, Frankenthaler reintroduces more overt elements of drawing such as the spindly graphic lines intersecting the coloured contours of “Mornings” and “Barbizon”, both 1971.

Mid-decade, Frankenthaler turns drawing inside out with works such as “Blue Bellows” and “Sentry”, both 1976, in which she masks out strips of bare canvas so what appears to be drawn is, in fact, just the absence of ground.

After this, she begins to experiment with mark-making using squeegees to create works including “Mineral Kingdom” (1976). “I would go to the studio where Helen would show me with pleasure a new kind of squeegee she had found,” Elderfield says. “People would bring her these things — you knew that if Helen invited you for a drink, you wouldn’t take a bottle of wine, you’d take a squeegee. She loved materials.”

In the extraordinary “Grey Fireworks” (1982) Frankenthaler snakes drawn elements through the clumps, swathes and splotches of colour. Then, by the latter part of that decade, she was consolidating, pulling together various elements of previous work to create pictures such as “Syzygy” (1987).

The Gagosian exhibition folds into a revisionist trend centred on Frankenthaler’s work, seen also in last year’s “Pretty Raw: After and Around Helen Frankenthaler”, at the Rose Art Museum. It traced the tentacles of influence emanating from Frankenthaler’s process-driven art and her unleashing of colour through subsequent generations of artists as diverse as Andy Warhol, Judy Chicago, Carroll Dunham, Lynda Benglis, Sterling Ruby, Mark Bradford and Laura Owens. “The generosity of Helen’s work is one of the reasons why it has been so open to so many other artists — they can find their own way of looking at it,” Elderfield says. “There is enough in the work for anyone to engage with.”

Such diverse responses are testament to Frankenthaler’s art. “If a work can be wrapped up easily then it usually isn’t very good. Helen made the kind of art that gives you a lot of problems when you engage with it. That happens when the work is deep enough and rich enough,” Elderfield says. “Helen was a radical: she never stopped inventing.”

–Guardian News and Media Ltd

“Line into Color, Color into Line” runs at the Gagosian gallery in Beverly Hills until October 29.