Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy is a documentary filmmaker whose 2012 film about acid violence, “Saving Face”, made her the first Pakistani to win an Academy Award. This year, she is nominated again for “A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness”, which tells the story of 19-year-old Saba Qaiser, from the Pakistani province of Punjab, whose father and uncle shot her in the face and threw her in a river because she had married without her family’s consent.

Because she had tilted her head at the last minute, Saba survived the shooting and managed to get to a petrol station for help. But although her father and uncle were subsequently arrested, Saba came under pressure to forgive them, which under Pakistani law means they would escape further punishment.

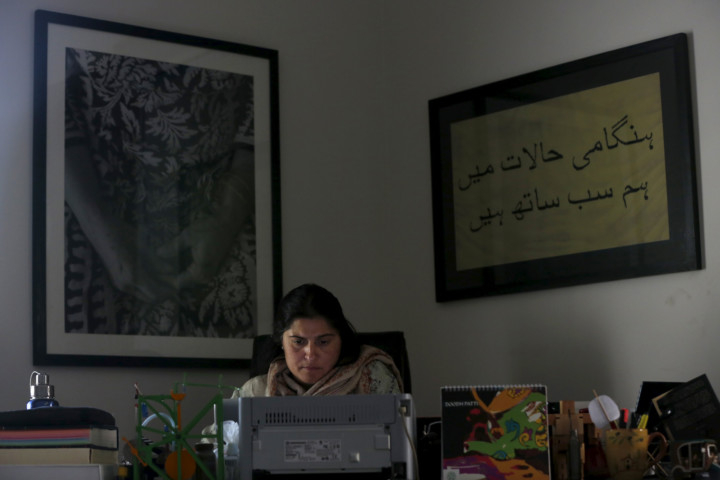

Excerpts from an interview with Obaid Chinoy:

How did you come across Saba’s case?

I wanted to tell a story about “honour” killings, from the perspective of somebody who had survived, because almost always victims of “honour” crime die, and it’s very hard then to tell the story. So I was searching for a survivor, and one day I read in the newspaper that a girl had been shot and put in a gunny bag and thrown in a river, and survived, and was in a hospital. So I went off to try and find that hospital.

And obviously you did...

Yes, I found her in hospital — it must have been about two days after she had been shot. We got permission from the hospital, and we spent a lot of time speaking to her; you know, she was very open to telling her story because she believed very strongly that she didn’t want anyone else to go through what she had.

She must have been in a great deal of pain, and shock?

She was. She had this extraordinary kind of will though — this defiant will about her, even on day one. And she just took to filming, as if she was born for the camera. But she never did anything extra, she was who she was; and you see that as the film progresses, you see her demeanour, the way she reacts, the way she laughs — it’s all very natural.

She was also facing the immensely painful reality of her own family having tried to kill her, and now ostracising her. How common is that situation?

It is a pretty common narrative, because about a thousand women are killed in “honour” crimes in Pakistan every year; and we think the number is much higher because many cases go unreported. The problem with “honour” killing is that it’s considered in the domain of the home.

People hush it up: a father kills a daughter, and nobody ever files a case. The victim remains nameless and faceless. People feel, “If we register a case, it will bring shame to the family.” So this [film] is a way for us to bring it out in the open, to have a national discourse, for us to say this is a crime, it has nothing to do with honour; it’s cold-blooded murder.

What has the reaction in Pakistan been like?

One of the most encouraging things was that the prime minister made a statement after the [Academy Award] nomination. He said that he would work on “honour” killings and he wanted to hold the first screening at his residence. Now, that is a very brave statement to make, it’s also very forward-thinking. And we are waiting to hear back from the government about a date for the screening; we are hopeful that he will follow through on his statement.

And your view is that a change in law is the fundamental aim?

The thing about “honour” crimes is that there are people who don’t think it is a crime because people don’t go to jail. If you have entire towns and villages where people have killed their daughters or wives or sisters and not been to jail, you will think it is not a crime. The minute people start going to jail, it will act as a deterrent. People will know that there are serious repercussions. We have to take that first step.

One of the most disturbing aspects of “A Girl in the River” is the way Saba’s father believes that his actions have served as a warning to his other daughters, and that his standing in the community will improve.

As you see at the end of the film, he feels that he has done something right, and that people grant him more respect, and he says that his other daughters are getting very good proposals [of marriage.] This is what happens: this grandstanding that takes place, people become huge in their community, they aren’t looked on as criminals. If he had gone to jail, the narrative would have been very different.

It’s also extraordinary to see how the female members of Saba’s family backed him up.

Well, you know, they’ve been brainwashed that this is something that would elicit this kind of response. His sister was the most shocking for me: she said, well, what she did expect? She ran away. She got married out of her choice. This was bound to happen.

Your work puts Pakistani society under the microscope — but how much do you think it is changing?

Pakistan is changing rapidly. Sixty per cent of the population is under the age of 25, you have a high use of cellphones, of the internet. How long will people be able to hold women back? More women are going to college and schools, and I see cracks in traditional society.

More women know their rights because of how interconnected they are; they’re no longer isolated. Even in the remotest villages you have cellphones, and of course this is going to shake the status quo in a patriarchal society ... Women now want a greater say, they want greater economic independence, they want a greater say in the kind of marriages they make, the kind of education they get, where they work.

How much do you see your role as enabling and pushing for change as well as simply documenting what you see around you?

I like to talk about the things that people don’t like to talk about. I like to have the difficult conversations. While society is changing rapidly, there are all of these issues that we’re not addressing. We think that by hiding them, they will go away. My documentation is not only of the issues, but also of the people who are fighting them, the heroes you don’t know, who risk their lives every day.

Have you encountered resistance?

The biggest criticism that I get is: “Why are you showcasing stories that make Pakistan look bad?” And my response is: “Why are you shooting the messenger? Why don’t you fix the problem?” How many filmmakers in Pakistan are making films about acid violence, about “honour” killings, about child marriage, about rape? Very few. I live in Pakistan, I want it to become a better country than it is, and I think that by having these discussions, by bringing these films out, we as a country are forced to acknowledge them.

Did you always know you wanted to tell these stories through film?

I was actually a print journalist — I started writing for newspapers when I was 14 years old. And I was writing in newspapers all through my teenage years, and then when I went off to college in America. Then 9/11 happened, and I wanted to move from print, because it was one-dimensional, to something that was visual. I didn’t even know what a documentary film was — I’d barely ever seen one. Don’t forget I grew up in Pakistan when there was only one television channel. But then I did a lot of research — did I want to go into news, or something that was long form? And that’s when I stumbled upon documentaries.

How much has being a female filmmaker affected issues such as access, or how people react to you?

I think that I’ve been fortunate to be a female filmmaker. It allows me greater access, greater sensitivity in some cases to some of the subjects. I can go into places that men cannot as easily. Being a woman has really been an asset for me, and I don’t think I’d be able to tell the kind of stories that I do if I was a man.

This Academy Award nomination comes in a year when diversity is a huge issue. What’s your feeling about that?

I think that the Academy is a reflection of Hollywood. I think that you cannot blame the academy, you have to begin making changes in Hollywood first. It’s only when you bring diversity into Hollywood that you can bring diversity into the Academy Awards.

Having said that, if you look closely this year, there are a number of filmmakers from around the world, outside of the foreign-language categories. When I’m looking at diversity, I’m not looking at the actors and actresses, I’m looking at my field — and in my field, there is diversity this year. There’s a film from Pakistan, a film about the Holocaust, a film about Vietnam, one about Ebola and Africa — the diversity’s immense, just in the subjects that are being tackled.

What’s happening in the documentary world? There are great practitioners, but is it sometimes a struggle to get films made?

Yes. But the good thing about documentary films is that you have some major players coming in. Netflix, Amazon, these will all change the way documentary filmmakers tell their stories — the experimentation is enormous.

How do you feel about your prospects on February 28?

This is a very competitive year — there are some fantastic films out there, and some fantastic filmmakers. You never know until that envelope is opened who’s going to be announced. So I am putting all my energy into getting the Pakistani prime minister to make good on his promise. To me, it will be a bigger win if we do manage to at least begin to send people to jail for “honour” killings. That’ll be a much bigger win.

And what news do you have of Saba?

Since the filming stopped, she’s had a son [with the man she chose to be with], and she’s basically hoping to educate him. A donor has come forward to give land to her, so she has land in her own name. She didn’t even have a birth certificate or an ID card, all of that has been processed. She finally has an identity of her own.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

The 88th Academy Awards ceremony is on February 28. “A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness” is nominated in the documentary (short subject) category. Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy hopes the film will be shown later this year in communities across the UK where “honour” crimes have occurred.