Thirty-seven years ago, Syrian sculptor and artist Rabea Alakhrass left behind fragments of his heart in the neighbourhood of Juret Al Shayah in Homs, Syria, and emigrated to Saudi Arabia.

When asked about the state of his hometown today, he replies in a tone filled with pain and heartache, “In my town today, there is not one stone left standing on top of the other.”

Alakhrass graduated from the College of Fine Arts in Damascus University in 1979. Among his first works is a sculpture named “The Detainee”, presented as part of his thesis in an exhibition held on the incidents that took place in Tel Al Zaatar Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon in 1976. After this exhibition, the Syrian artist left for Saudi Arabia, where he has been residing ever since.

Today, Alakhrass’s sculptures grace streets across the Arab world, including in Damascus, Amman, Cairo, Dubai and Sana. In Saudi Arabia, he has constructed 20 different sculptures, ones that have become iconic symbols and landmarks for Saudi citizens and residents.

The artist’s tryst with creativity began at a young age when, as a boy scout, he discovered the joy of playing with mud. Although oblivious to his passion at the time, he later realised that that was the beginning of a lifetime journey into the art of sculpting.

As for inspirations, he says he is not always sure where they come from — “an idea can spring from the smile of a child, or from an interview like this one, or perhaps after witnessing the death of a bird. However, with the death of a homeland, the wounds of a soul require a long time to heal; what is conceived as a consequence seems to be premature and defective where the products created are thousands of times smaller in size than the reality on ground.”

Syria’s condition today, he says, is much more appalling in intensity and strength than any creation possible. “What is happening is fatal. It does not create but kills.”

For Alakhrass, symbolism embodies the journey of an artist’s mind into the deep and profound. And he believes all symbols in life embody two faces, positive and negative “The eagle, for example, is a symbol for majesty and magnificence, and at the same time, as it is a bird of prey, it can embody predatory and ravenous characteristics.”

Asked about the women in his sculptures, Alakhrass expresses with the passion and charm of an artist, “A woman is a mother, a sister, a wife, and a beloved. A woman is fertility. A woman is a homeland. Women are mothers to our universe.”

In one of his exhibitions, titled “The Invisible”, the artist explores the unseen within the internal parts of our beings. He explains, “Our glass mirrors only reflect the external — that which is floating on the surface of things. But if we were to take a closer look at the invisible within our beings, we would find, much to our dismay, hollow cavities and dark abysses. We would see wounds and feel pain. So, I design the glass in my exhibition to explore the internal rather than the external.”

Referring to a sculpture in which a hand is separated from a human body by glass, Alakhrass explains, “The glass between the hand and the body embodies the barrier that needs to be permeated to see and touch the truth, the internal, and that which is invisible to the naked eye.”

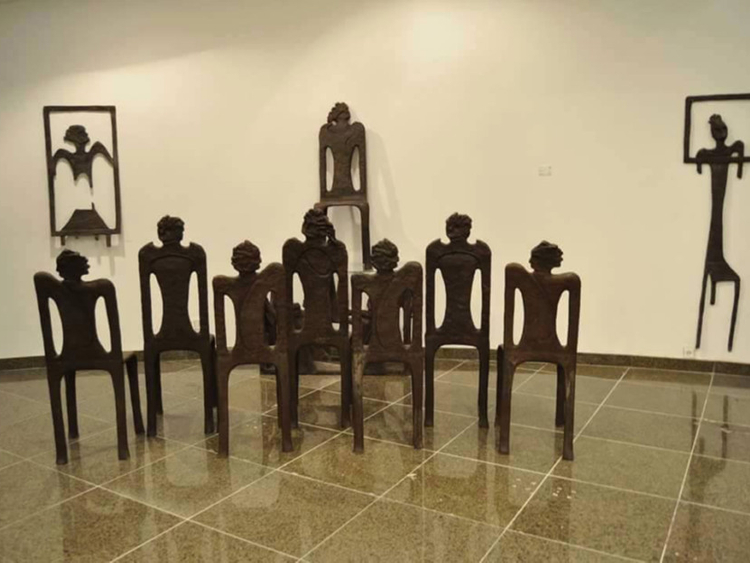

When asked about the significance of chairs in his works, he says they are a sacred symbol. “It was mentioned in the Quran. In today’s era, the chair has thousands of meanings, but predominately it represents the throne of power. Here, I take this notion a bit further in my works and I attach the figure of power to the chair itself, where the person and the chair become one. Accordingly, all other positions of power also become chairs of different sizes, positions, and functions. Within this space, one chair is surrounded by a number of smaller ones, some in front and some in the back, reflecting the imbalance found in places and positions of power.”

The artist goes on to say that he has also framed and hung some of his chairs on walls in an attempt to demonstrate the notion of eternalising and immortalising a figure of power within the borders of a frame.

The sculptor, who is also known to ;break his sculptures into parts, says that is his way of breathing life into his works. “A sculpture is like a dead body, inanimate and lifeless. In order to give it liveliness, I divide it into separate parts so that the eye sees it differently from different corners. This creates an illusion and adds an element of life to the bodies of my sculptures.”

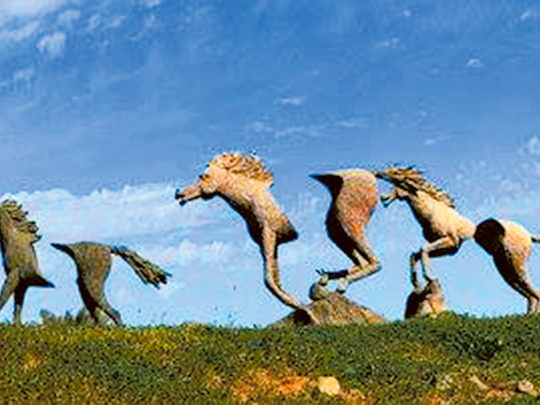

One example that powerfully captures Alakhrass’s idea of adding animation to a sculpture is found in a herd of horses he sculpted on the way to Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport. In this scene, the bodies of the horses look as if moving and racing the passing cars.

As for a piece dearest to his heart, Alakhrass expresses the answer fluctuates depending on time, and also on his personal progress within time. “When he looks at his past works, he says he finds himself evaluating his progress, “and perhaps even discovering some flaws. In short, the collage of my works represents who I am and who I was at different times and places in the journey of my life.

“One of the first works I constructed in Jeddah is a 12-metre-high horse. Although I do not often visit it, I do love it because it represents my accomplishment during the beginning of my journey,” he says. “You see, the more time passes on a work, the more value it gains in that place.”

And so too, is it for memories of his homeland. “Even though my hometown is Homs, I love Damascus just as much because that was where I developed my identity, and social and political consciousness,” he says.

Then Syria began to regress. “Our civil society began to wither, as well as our theatre and arts. Education began to take on one face and one front. Everything looked the same; this was even reflected in our arts where there was no longer any individual characteristic. Everyone had to walk the same line. We began to resemble one another, and, we were not attractive any longer, stripped of colour and beauty.”

After a few moments of silence, he adds, “You see, this kind of repression does not create a homeland. It creates copies and slaves. This was Syria. Security in Syria was made up of lies. It was a result of fear; but fear does not embody the true essence of security. Perhaps there was a sense of security amongst family and friends — average people like us — but we were always frightened of the Other. After many dark years, we had no other choice but to call for change. Sadly our dream of change was also shattered.”

Yet hope remains alive in the Alakhrass’s heart. With great conviction, he says, “There must be hope! Perhaps Syria will never be what it once was. There is a whole lost generation of Syrians today, a defected generation that has been denied a childhood, a home, an education, and one that has been stripped of its dignity. Syrians have been humiliated whether on borders or in their homeland; they are not welcomed anywhere in the world. There seems to be a war against the Syrian people today, against thousands of years of civilisation. My hope is that this war is defeated.”

Ghada Alatrash is a Syrian writer and poet based in British Colombia, Canada.