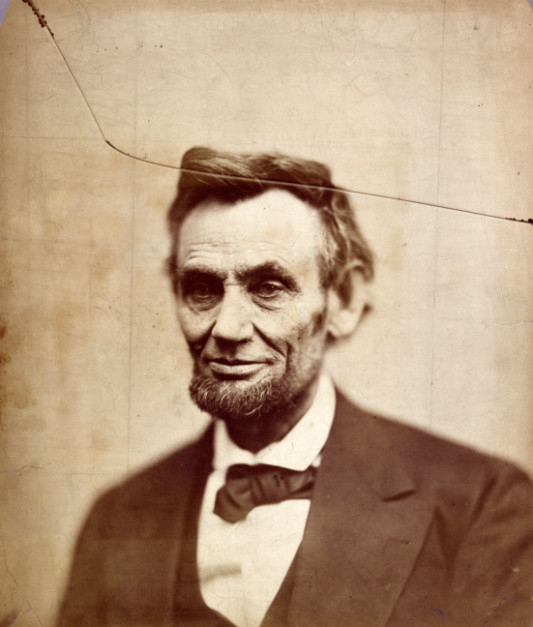

The crack in the famous “cracked plate” photograph of Abraham Lincoln appears to be a fissure in the paper on which it is printed, a detail not apparent when one looks at reproductions of what is one of the most famous and evocative portraits of the 16th president.

Alexander Gardner made the image only weeks before Lincoln was assassinated, but before the photographer could make multiple prints from the fragile negative, it broke, so only a single photograph was made before the glass original was discarded.

Photographs of this period are highly sensitive to light, so this powerful Lincoln portrait is rarely shown. But the National Portrait Gallery has made the cracked-plate Lincoln the centrepiece of a new exhibition devoted to Gardner, “Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872”.

Those with an interest in the Civil War, and Lincoln, will find the show thoroughly absorbing, but it is far more than a Civil War exhibition.

Curator David Ward is sketching a larger picture of America in the late 19th century, a country transformed by war, disillusioned yet ambitious, moving seamlessly from internecine strife to genocidal violence against its native population.

Gardner, he argues, witnessed and recorded “the great historical moment in American history” when the country moved from an Arcadian sense of self to a more modern self-conception: transcontinental, increasingly industrial, self-aware in a historical sense, even perhaps cynical. “What like a bullet can undeceive?” asked Herman Melville in his “Shiloh Requiem”.

George Steiner noticed something similar in Europe in the wake of the French Revolution and Napoleon: “Henceforth, in Western Culture, each day was to bring news — a perpetuity of crisis, a break with the pastoral silences and uniformities of the eighteenth century.” A half-century later, America was shocked by war into a new age of perpetual busyness.

Gardner, a Scottish-born photographer who was working in the Washington studio of Mathew Brady when the Civil War broke out, followed the action as closely as a photographer encumbered by large equipment and a complicated photochemical process could at the time.

Like Roger Fenton, the English gentleman who fitted up a wagon to document the Crimean War in 1855, Gardner created a travelling studio to bring the battle home to ordinary civilians. But unlike Fenton, who considered corpses distasteful and didn’t photograph them, Gardner (steeped in the progressive, working-man’s political issues of the day) turned his lens on the remains of young men.

Hidden realities

This was new and deeply shocking, and it brought one of the hidden realities of war home to people who were inclined to indulge a more romantic and heroic conception of armed conflict.

Far more gruesome and graphic images of war are now available to anyone with an internet connection, and by contrast Gardner’s photographs seem rather tame. But he was pioneering a field of representation that had no real precedent, and that, according to Ward, may explain one of the most notorious episodes of Gardner’s career.

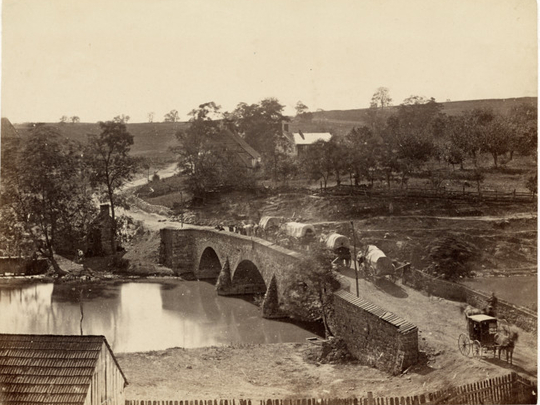

After galvanising audiences with images from the Battle of Antietam, Gardner went to Gettysburg in 1863, where he apparently moved a corpse and positioned a rifle nearby to create a more dramatic image of a “Rebel Sharpshooter”. This fabrication, Ward argues, was a response to the enormity of the thing Gardner was trying to capture, a lapse not just into dishonesty but sentiment. “Caught at a transitional moment, Gardner did not trust the images his camera captured,” reads the wall text. “That this photographic construction would be more marketable to a public still steeped in Victorian sentimentality only adds to Gardner’s malfeasance.”

Gardner not only photographed the carnage of war but was a popular maker of portraits, and the walls of the exhibition are filled with a who’s who of the power brokers, political and military leaders, and celebrities of the day. By one estimate, more than 100,000 images of the Civil War were made by photographers such as Gardner, and millions of these images circulated via engravings in the popular press and directly through the sale of photographs, particularly popular stereographic images.

The appetite for news of the war was insatiable, and one sees in Gardner’s work the emergence of notoriety as a public phenomenon. Famous or notorious people, such as the Southern spy Rose O’Neal Greenhow, enjoyed a new kind of celebrity, as did famous places associated with important historical events, such as the otherwise unprepossessing Marshall House, ann Alexandria, hotel that was the site of Col. Elmer Ellsworth’s death — considered the first Union casualty of the war.

Gardner was Lincoln’s favourite photographer, and the exhibition displays several of the iconic portraits he made of the president. Perhaps that encouraged others to have their images made by the photographer, including five Union officers who are seen poring over what appears to be a map spread on a table. Among them are Philip Sheridan and George Custer, and this image becomes central to Ward’s argument about the continuity between the Civil War and the Indian Wars that would follow. Photographed in 1865, these men would go on to leading roles in the lopsided, brutal “wars” against Native American tribes in the West.

Gardner took his camera to the site of these traumas, too, photographing forts and treaty signings. But perhaps most moving are the studio portraits he made of Native American leaders who came to Washington for negotiations. Throughout the exhibition, one gets tiny clues about the architecture and decoration of Gardner’s studio (at Seventh and D streets NW): a rug, a room with windows on two sides, a distinctive baseboard. These details give the otherwise de-contextualised, seemingly objective portraits a moving specificity, grounding them in a place, a room, that connects the subjects to each other in a web of significance and interrelation.

The recurrence of these small markers somehow makes the photographic act feel more intimate, and intrusive. Detail is the essence of photography, especially photographs of historical events and personages. Detail is what makes us stare and look into the image for truth, even when the images are staged or conventional. Detail can unravel almost any photograph, leaving us with a sense that we have penetrated time and seen through the veils of propaganda, myth and ideology.

Gardner’s images of tribal leaders in his Washington studio unravel the myth of the West as a faraway land of noble Indians fighting equally noble cowboys. It places Native American leaders in the same spot where American military figures were photographed, giving them visual if not actual equality.

The centrality of the cracked-plate image in the well-designed and beautifully installed exhibition is related in part to this sense of detail. The physicality of the crack invites a similar passion to look into the image, a similar illusion that reality is somehow lurking inside it. The cracked-plate portrait is a powerful exception to the usual dynamics of photography, which is an essentially industrial, reiterative process. The single print made from the faulty plate is more like a painting: There is only one, and it has the status, even the aura, of a solitary piece of art made by human hands.

It captures Lincoln in a slightly fuzzy focus, softening his features, and, unlike many portraits, it doesn’t depict him facing the viewer straight on. Rather, his shoulders are turned, and at slightly different levels; he stares not at the viewer (as in a penetrating 1863 Gardner portrait) but beyond and slightly to our left.

It distils all of the tragedy of Lincoln’s death — the loss of compassionate leadership at one of the most critical moments in world history — into a single, comprehensible and deeply tragic picture.

That’s myth, too, a retrospective reading of a man who, on February 5, 1865, had no inkling of what would soon befall him at Ford’s Theatre. Nor should the crack itself be idly accepted as a metaphor for what the nation had experienced, and for the ongoing decades of racial oppression that would follow. But it’s futile to try to be objective about these things.

We know little about Gardner himself and why he gave up photography in 1872. We don’t know how canny he was about images and public opinion. But this exhibition demonstrates that he was a quintessential figure in the emergence of a modern image culture, with its enormous power to make us feel participants in history and its still vital though illusory promise that the mechanical image can trump the fluidity of time and arrest for a moment the forces that shape our world.

–Washington Post

Dark Fields of the Republic: Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-1872 is on view at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington until March 13.