“J’aime les panoramas” says the banner on the J4 pier in Marseille’s Vieux Port. The panorama is indeed magnificent: the honey-hued 17th-century Fort Saint Jean gleams against a scintillating sea, the domes of the striped neo-Byzantine Cathédrale La Major rise silhouetted against crystalline skies.

The J4 pier is one of France’s most historically loaded sites. To millions of migrants and refugees — Algerian arrivals since the 1960s, fugitives from Nazism in 1940 — the J4 offered a first or last sight of Europe.

The quay is no longer an embarkation point, but its surrounding buildings remain a palimpsest of French military, civil and religious authority in a city rooted in a multicultural past and present: today a third of the population is Muslim. No panorama here can be innocent.

The impressive winter exhibition about political and cultural appropriation of landscape at MuCEM (the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, sited on the J4 esplanade) opens with Michel Hazanavicius’s exquisitely evoked 1950s pastiche “OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies (2006)”.

A Closer Grand Canyon by David Hockney, 1988

Its crass/charming hero Jean Dujardin, a young Sean Connery lookalike agent, assures his Muslim contacts of Islam that “you’ll grow tired of it ... it won’t last long” as he comically misunderstands his Egyptian mission.

Viewing the bright Suez vista with juvenile insouciance, Dujardin’s comment “I love panoramas” gives MuCEM’s show its faux-naive title, and encapsulates its feel-good yet edgy tone.

Every work here invites multiple readings or perspectives. Juan Muñoz’s “Balcon/nes” is an isolated balcony railing incongruously mounted to transform a bland white wall into a space for contemplation.

Jeff Wall’s lightbox transparency “Restoration”, featuring actors playing conservators placed inside a vintage Alpine panorama, emphasises the tensions of the medium: is a panorama architecture, painting, game of illusion? David Hockney’s vertiginous 60-part gold, crimson, scarlet, orange, purple canvas “A Closer Grand Canyon” defies photographic renderings with the “closer” approach of painterly geometric patterning.

Hybrid culture

The panorama is a perfect subject for MuCEM. Marseille’s flagship museum, inaugurated in 2013, was designed by Algerian-born Rudy Ricciotti and at once delights, bewilders and imaginatively embodies Marseille’s hybrid culture.

Clad in a lacy concrete mesh reflected as ripples in the sea, and filtering ever-changing dramas of light and shade into the interior, Ricciotti’s half-veiled building is the show’s star exhibit.

Its rooftop spectacle of coast and harbour ranks among the best museum panoramas in the world, yet MuCEM’s slippery, shifting styles underplay any triumphalism.

Accessed via bold ziggurat ramps and shiny black bridges connecting it to the Fort and expressing industrial modernity, the building is dominated in contrast by its latticework screen alluding to the filigree mashrabiyas of traditional Arab housing.

Many of the conceptual works here convey similar ambivalence of appearance, some resonating intensely with the terrorist attack in Paris.

Renaud Auguste-Dormeuil’s “Hotels des transmissions — jusqu’a un certain point” (2007) are urban panoramas reclaiming the graphic vocabulary of orientation tables, though indicating not places of beauty but security risks: military, industrial, commercial infrastructure as potential bomb targets.

Der Wanderer 2 by Elina Brotherus, 2004

Alexis Cordesse’s monumental saturated photograph “Mur de Séparation” looks like a busy, casual, multicultural street scene but is a montage of superimposed close-up images of Jews and Arabs in occupied Jerusalem and the occupied territories whose paths would rarely cross: metaphor for invisible as well as visible political frontiers, for nervous juxtapositions of faces anywhere.

Panoramas, as this show traces brilliantly, were almost from the start about domination, persuasion, playing to the crowd. Irish painter Robert Barker invented a circular construction displaying a continuous landscape in specific lighting in 1787.

Immersive wall-papers such as Jean-Gabriel Charvet’s 11-metre “Les Sauvages de la mer Pacifique” followed: illusionary devices prompting dreams of the mythological elsewhere yet flaunting European control — aesthetic as well as colonial — over “primitive” territories.

In the early 19th century, Pierre Prévost’s vast cityscapes such as “Panorama de Constantinople” (1818) rapidly became popular.

In 1822, Prévost’s pupil Daguerre built a diorama theatre, a cylindrical room showing a large translucent atmospheric canvas — the brooding “Effet de neige et de brouillard à travers une colonnade gothique en ruine” (1826) is an example here — illuminated from different angles and changing with the effects of light: a precursor to the daguerreotype.

Audiences were awed, and the propaganda value of panoramas was soon grasped: Napoleon III commissioned Jean-Charles Langlois’s multi-part turbulent painting of victory and destruction “Sebastopol”, shown a few years after the battle in a rotunda on the Champs-Elysées to 400,000 people.

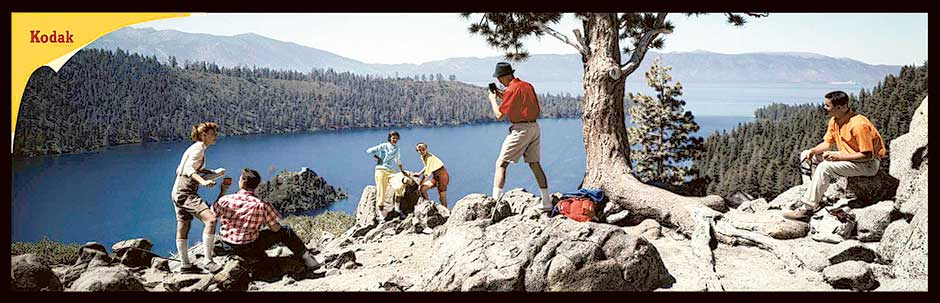

Love of illusion, the desire to suspend disbelief, is timeless, as the more eclectic exhibits here demonstrate: stereoscopic “View Master” cards devoted to different countries; “Colorama” photographs of campers, skiers, cowboys in Lake Placid, Aspen, Wyoming, displayed as monumental backlit transparencies inside New York’s Grand Central Station, which began as Kodak advertisements but developed into kitsch, sentimental yet enduring promotions of American values, running from 1950 to — extraordinarily — 1990.

But the real successor to 19th-century panoramas was cinema, which Stalin called “the greatest medium of mass agitation”.

The range of films showing here is superb. Sergei Eisenstein stages Soviet-German relations as 13th-century epic in “Alexander Nevsky” (1938). Jean-Luc Godard’s meta-picture “Le Mépris” (1963), about a producer trying to adapt “The Odyssey”, plays on yet undermines Hollywood tropes of Mediterranean scenography. Wim Wenders’ road movie “Paris, Texas” (1984) views the romance of America through a windshield of highways, canyons, billboards.

We all see the world through a screen today; landscape art as a result is increasingly experiential.

MuCEM traces the northern sublime through two centuries, from Norwegian romantic painter Johan Christian Dahl’s “Vue depuis Bastei” (1819) to Olafur Eliasson’s immersive “360 degree Room for All Colours” (2002), a round light sculpture enveloping us in a fluorescent rainbow cavalcade whose computer-generated shifts distort space and perspective.

Conceptual balance

Eliasson’s installation gives a northern, conceptual balance to the Mediterranean theatre of MuCEM itself.

Ricciotti says he designed the museum “under the pressure of that metaphysical horizon that is the Mediterranean, of that cobalt blue that becomes Klein blue then ultramarine, that drives you mad after a while and turns silver when the wind gets up. It’s violent.”

No exhibition until now has lived up to this building, but MuCEM is now on a roll: an exploration of Algerian history and a Picasso show follow the thoughtful dovetailing of politics and art which makes “J’aime les panoramas” such provocative pleasure.

–Financial Times

“J’aime les panoramas” will run at MuCEM, Marseille, until February 29, 2016.