Elihu Yale, the enterprising and corrupt colonial governor who gave a modest bequest and lent his name to Yale College, made much of his wealth trading diamonds from mines on the Deccan Plateau of south-central India.

Yale’s name is a fascinating footnote to a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which examines the artistic production of the small but culturally robust sultanates of Deccan India. Yale, who exemplifies the reach of Deccan treasure, becomes one prism through which to see a show that is ultimately an exploration of cultural porosity, full of the material remnants of trade and colonialism, dynastic intrigue, war, and religion.

Consider the term “West” in the context of this exhibition. Even as European powers were establishing fortified entry points along the coasts of India during the period explored here — the 16th and 17th centuries — the local meaning of “Western influence” was all about Persia and the empires that spread Persian culture throughout the region. It meant the Safavids and, closer and more menacingly, the Moguls, who eventually subsumed the Deccan sultanates into their expanding realm.

A basic conflict between “Western” and local populations influenced the production of imagery and art in the region. But, so too, did other conflicts and tensions, including the Sunni-Shiite divide, and political strife with neighbours to both north and south.

Among the most gifted of Deccan political leaders was Malik Ambar, prime minister of one of the sultanates, who was born in Ethiopia. Among the exports of the region is the kind of carpet that can be seen draped over a table in Vermeer’s “Young Woman with a Water Pitcher”, painted in the early 1660s.

And among the most fascinating objects in the exhibition is a watercolour and ink painting on paper, probably made around the time of Vermeer’s painting, which shows an oversized parrot looming in a mango tree above a white ram. The bird is clearly based on an image by the Dutch artist Adriaen Collaert, which circulated in print form; but the scale is strange, with the plump and colourful parrot filling at least half the tree, dwarfing the fruit that grows thereon.

Games with scale turn out to be one of the distinguishing eccentricities of Deccan art. Flowers, butterflies and other insects may be wonderfully enlarged in relation to the human figures nearby; often it’s not clear if this was the result of misreading an earlier or foreign source, such as the Collaert drawing, or a whimsy that needs no other explanation than pure inspiration.

Clouds, skies and background landscape are also sometimes shocking in their loose, expressive execution, as if the meticulous figures of Mogul or Persian art have wandered into a Van Gogh painting.

And there are works such as a series of marbled drawings, in which the long-established practice of using dyes and inks floating on a liquid bath to create elaborate, abstract “marbling” effects was combined with representational imagery. And so a woman wears a marbled dress, an elephant fights with a horse against a dramatically marbled backdrop, and a religious ascetic rides an emaciated marbled horse.

This last image, which appears in two different versions, is particularly striking. Both the horse and the man riding it are skeletal, the effect both tragic and comic; to Western eyes it suggests famous allegories of death on a horse by Drer, and as the catalogue authors point out, the expression of the horse, especially the hangdog angle of its neck and head, is close to an image by Bruegel the Elder. Don Quixote’s steed, Rocinante, will also come to mind.

Those connections, especially to Cervantes, are fanciful, but one can never be quite sure. The dates line up for these 17th-century images to have some possible relationship to the earlier images by Drer and Bruegel.

At this point, however, the visitor should pause. Filtering the art through Western referents is too tempting, and too facile. One can see the legacy of that in how many of the painters are named: the Paris Painter, the Dublin Painter, the Bodleian Painter.

Naming anonymous artists for institutions or locations of where their work is preserved is a convenient shorthand for Western scholars, but symptomatic of a reflexive mental habit of appropriation and classification. Perhaps it is a useful habit, and an unavoidable one, but the pleasure of the exhibition is its invitation to see without naming, sort without using borrowed categories, connect without trivialising.

Often, when exploring the art of this period, the viewer feels obliged to be seduced by detail. Mogul art and many of the works in this exhibition are exceptionally detailed and delicate, and the museum helpfully provides magnifying glasses to let visitors dig into the miraculous refinement of line that sometimes defies detection by the unaided eye. It is worth using the glasses, but it’s also possible that the meaning of the art isn’t located in the mere virtuosity of details.

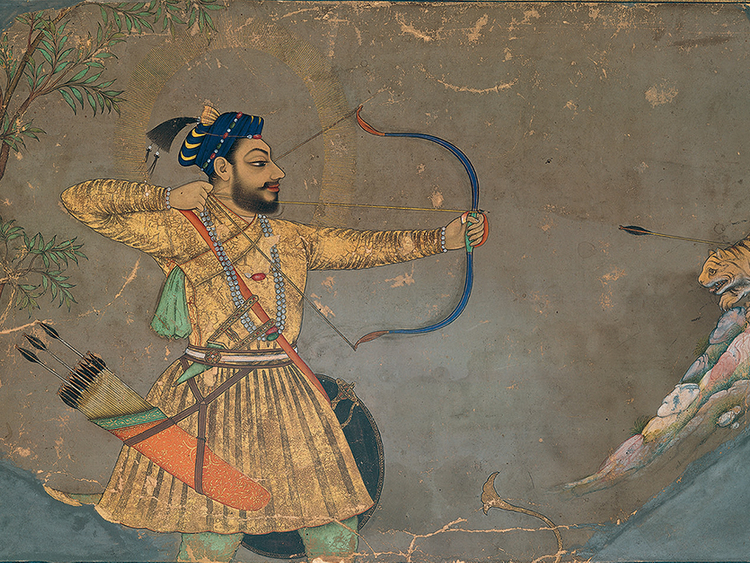

One particularly powerful work, attributed to the “Bombay Painter”, shows a prominent sultan of Bijapur drawing his bow and aiming an arrow at a tiger, who menaces him from the opposite side of the fragmentary work. There is astonishing precision to be discovered in the sultan’s beard, and hidden fancies in the rocks beneath the tiger. But it is the open space, the blankness of the gulf between man and animal, hunter and prey, that gives this painting its emotional force.

And while it may seem that the tiny drop of gore drawn forth by the arrow striking the tiger sums up the painting and its virtues, it’s also worth spending time with the peculiar, lightly smiling impassivity of the sultan’s expression. If there is a recurring tone that links many of the disparate works in this exhibition, it is seen here: A lightness of affect, an almost amused acceptance of the world, including its many dangers.

Art doesn’t register social currents like a seismograph. Societies that enjoy peace and abundance may, in their art, seem preoccupied with death and the loss of those boons; and societies, such as the Deccan sultanates, that lived surrounded by dangers, may through worldly sophistication convey a genial condescension to those threats.

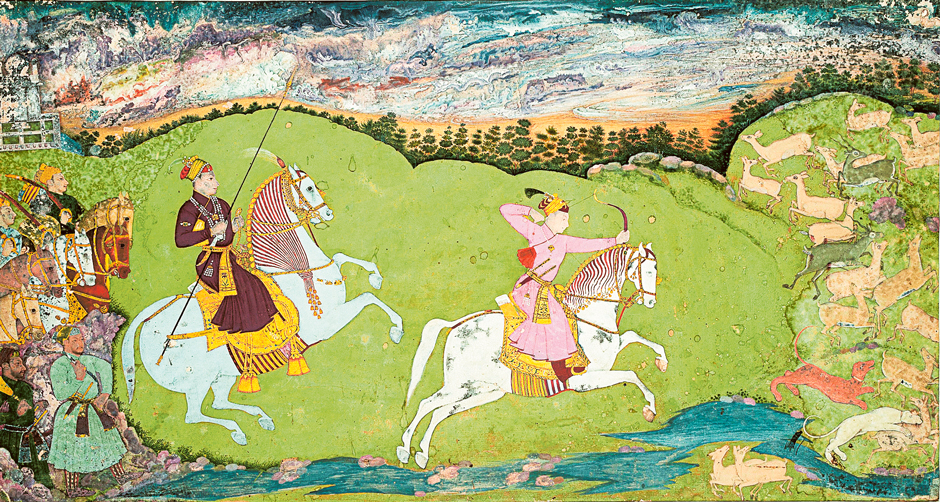

Here and there throughout the exhibition, you detect the telltale signs of the kind of playfulness that an anxious people use to mask what unnerves them. In another image of the same sultan, also attributed to the Bombay Painter, a blue- and gold-flecked curtain is apparently drawn back to reveal a garden beyond. But the curtain is also remarkably like the night sky itself, as if the mantle of a starry night has been drawn back to reveal a layer of cultivated nature beyond.

A similar game may be happening in a curious painting of a musician, or ruler, seen in profile, with a prominent curtain drawn to reveal what may be the night sky, or just another swath of nocturnal fabric behind it.

These are complex games, with the suggestion that perhaps it’s folly to believe that drawing back the curtain is akin to discovering the truth. The world, both natural and man-made, both cultivated and wild, both within us and without, is always a scrim; going into this illusion yields only more scrims behind it.

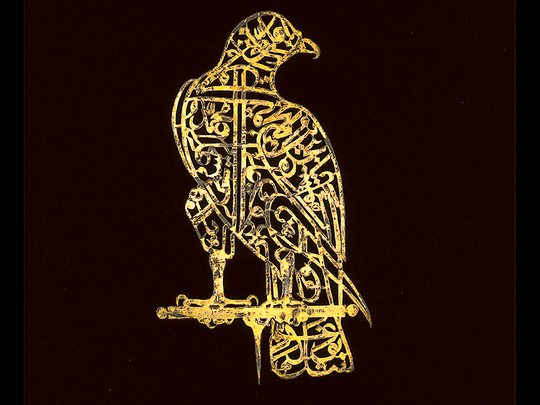

If we believe this art is operating at this level of richness and subterfuge, the other objects on display — the breathtaking gold illumination on dark paper, the “bidri” metal works with glistening silver and brass against a matte black background and “kalamkari” dyed fabric paintings with their array of European and local figures — complete the picture of a society that articulated refinement to the last degree of subtlety.

Perhaps at that point — the full emotional and intellectual realisation that the Western viewer is out of his element and beyond his depth — it’s safe to indulge analogies to art of the West.

And they will flood in: A painting by Ali Riza of a prominent sultan, with its majestic figure in a sumptuous cream-coloured robe set against a dark, architectural background, feels rather Dutch, like a painting by ter Borch or Vermeer; an image from the early 17th century showing a legendary talking tree from the Alexander Legend reminds one of the composite figures of Arcimboldo.

A palpable tension between the naive and the sophisticated runs through many of the works, which unleashes (as it so often does in Western art), conflicted feelings about the true wellsprings of innovation and the tendency to decadence.

The exhibition opens with diamonds, but don’t let that deter you. Jewels are to art what celebrities are to society, at best an ornament, more commonly an excrescence. But also: a commodity and a form of exchange. They have a Pavlovian effect on many visitors, inducing hypnotic billing and cooing as people encounter what seems the purest concentration of the gulf between the magnificence of wealth and art, and the insignificance of our own lowly selves, alienated by history and status from these concentrated markers of power.

But something, and somebody, has to pay for cultural expression, and these magnificent diamonds remind us of the concentrated magic and mystification it takes to support an hierarchical, artistically sophisticated society. They may flash intoxicating beams of light at the eye, but it’s best to think of them as the dung on which everything else in this endlessly absorbing exhibition grows.

–Washington Post

“Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy” is on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York through July 26.