The Mamounia hotel in Marrakech is a work of art. Trickling fountains, 20,000 square metres of fabulous mosaic tiling, intricately carved stucco, delicate cedar fretwork. In short, an aesthetic wonder which inspired a character in Paul Bowles’ 1952 novel Let It Come Down to declare: “Mamounia is just a little harder to get into than heaven.’

On February 24, this particular heaven opens its exotic doors to the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the first time the event has been held on the continent for, despite its title, the fair has been held for five years in London and last year in New York. Only now has burgeoning talent coincided with the hope of commercial success.

Why so long?

Founder Touria El Glaoui explains: “The mission was always to get international visibility for artists from the African continent and the diaspora and finding ways of getting them into different international connections and institutions and become included in the discourse. International recognition was very, very, low here so we had to be in London or New York, that was the strategy because there were not enough collectors on the continent.

“We wanted to show African artists in Africa but we are also a commercial venture and have to rely on the success of the galleries to make sure there is an outcome for all the art that is being presented.”

Now she is confident that the fair is established as a brand and has accumulated sufficient followers. As well as collectors from London and Paris, about 20 per cent of the 100 collectors who are expected to attend the fair are Moroccan and there are a strong gathering of international buyers from Dubai as well as French speaking countries such as Côte D’Ivoire and Gabon.

There are 17 galleries, of which three are from Morocco, showing the works of more than 60 artists and it is a statement of Africa’s growing impact on the international art scene and, Marrakech in particular, that the launch of The Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) is on the same weekend with an exhibition of photography.

In recognition of the growth in interest, British auction house Bonhams started specialising in contemporary African art in 2007 and saw average prices increase five-fold by 2016 and Sotheby’s first-ever Modern and Contemporary Art Sale took place in London in May 2017 and totalled £2,794,750.

But what is African art? How to define such a vast diaspora of talent particularly as so many artists have left their home countries to work and find inspiration abroad?

The veteran Ibrahim El Salahi, who is probably the oldest contributor at 88 and certainly the most esteemed for his reflective, socially aware works, says of his native Sudan: “It’s many countries, not just one. There are something like 200 languages but it is part of that same mixture of people from North Africa — Egyptians, Moroccans, Algerians and Libyans.”

So if one country is that disparate what to make of the vast continent?

El Glaoui, daughter of Hassan El Glaoui, one of Morocco’s leading figurative painters in the 20th century, points out that the clue to African identity, or perhaps its very diversity, lies in the fair’s title, 1-54.

“One continent, 54 countries,” she explains patiently. “We chose the title to emphasise that not everyone was the same but there was a common denominator. The title underlines the diversity and the multiplicity you can find on the continent. We are only touching the tip of the iceberg with the fair.

“It is unfair to define the art in a certain way,” she argues. “We do not represent every country because there are different influences, there are different cultures, and that is the beauty of Africa. It is such a beautiful world but it’s not a single country so there is no definition about what you can find.”

There is some common ground, however slight it might seem, such as the use of recycled material by many artists. El Glaoui says: “This has nothing to do being African per se but to do with the reality of life and a context in which countries suffer from pollution, where they have become the garbage of the world. You see a lot of artists working with textiles because it belongs to the culture of where they are from.

“There are also strong themes of gender rights and sex, migration and trade which are as relevant to global audiences as they are to African.”

As El Salahi says in his thoughtful way: “There are so many influences but what you see and what you know and how you mature with age affects a number attitudes and methods in your own work. My work is that of an individual. That’s the most important thing.”

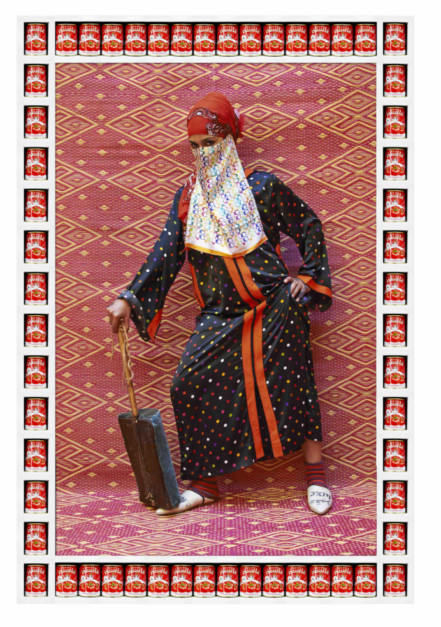

If one can make a generalisation about the works on display it is that many are forceful, dramatic images, often in bright colours, jumping off the walls with their energy. Few more than Hassan Hajjaj, who shares London’s Vigo Gallery with El Salahi —though there could hardly be more of a contrast between the two.

Moroccon-born Hajjaj, who is based in London and Marrakech was picked out for a prominent display at London’s Annual Royal Academy Summer Show last year by Yinka Sonibare, is perhaps best known for his photographic portraits, including the Kesh Angels series, which shows motorcycle gangs of Morocco in what is a bold mix of fashion shoot and rebellious street culture. Light-heartedly in your face they challenge Western perceptions of the hijab and female disempowerment.

Hajjaj owns a riad [a traditional Moroccan house] in Marrakech which he has allowed to be used by some of the younger talents of the region, few more original than the photographer Yoriyas who has captured street scenes in “Casablanca not the Movie” which attempts to set the record straight for those who see the city only through the glamorous prism of the film Casablanca with scenes of children playing football, market goers, party goers and quirky poses of bald men and playful girls.

Hajjaj has also taken over Les Comptoir des Mines, an Art Deco art space which once housed a mining company and curated a programme entitled “Mi Casa e tu Casa” (“My house is your House”) in which several young Moroccan artists have been given a free hand to show their works.

Tunisian Slimen El Kamel is a figurative artist who feels liberated enough in his series “L’Espace du Jeu” (“A Place to Play”) to ignore the strictures of Muslim teaching and portray figures, some lightly clad, in what appears to be a world of innocence and happiness.

“The work is very labour intensive,” says London gallerist Christian Sulger-Buel whose pieces range from £1,000 to £10,000. “He paints using a kind of pointilism and frames the paintings in the textile which Tunisian women use to protect their hair. Look more closely and you see in the background that there are weapons and wolves and an undercurrent of violence which contrasts with the dreamy atmosphere of the work.”

Nothing dreamy, nothing nuanced, about the works of Senegalese Soly Cissé whose tryptich, almost 14 feet by seven, is a chaos of grotesque and twisted figures. Powerful though it is, his most telling work is a series he drew when in hospital after major surgery.

Cissé is the son of a radiologist who as a boy started to draw on the X-ray sheets his father had dispensed with. In hospital for many months he expressed his inevitable psychological and physical trauma with the dark and brooding “Black Book Project”, taking images from magazines and scrawling over them before sticking them in a collage on pages of black paper and then immersing them with oils, leaving untouched the black edges as if to reference the X-ray paper he had used as a boy.

“You can feel the pain,” says Sulger-Buel.

If Cissé’s work is visceral, difficult to look at, the world of Walid Layadi-Marfouk has a formal, staged quality.

He is one of the artists being shown by London’s Tiwani Contemporary which was founded only seven years ago and benefited from the interest being generated in African art at the time — not least in the London auction houses and the formation of the 1-54 fair itself. Now they can charge prices that range from £1,000 to £10,000.

Only 22, Layadi-Marfouk is based in New York and Marrakech and has produced a surreal counter to what he feels are the false representations of the Muslim world by photographing his aunt and cousins in his great-grandfather’s riad in Marrakech.

In an oddly formal pose a woman stands on stairs lit by many coloured skylights in a long robe, another shows a woman prostrate in a bourgeois living room, apparently in prayer, kneeling underneath an elaborate framed mirror and before a blank TV.

Gallery owner Maria Varanava, of Greek-Cypriot birth but brought up in Nigeria, says: “He is investigating what it is to be Muslim. At first glance it seems to be an expression of nostalgia but really he is representing a world which is not seen and not portrayed by the media . He feels the media often misrepresent Muslims and he is avoiding any stereotyping. As Walid says: “There is no single Muslim reality.”

In stark contrast, in one of the special shows at the fair, veteran US-based Ouattara Watts, who has shown at the Whitney Museum in New York and Venice Biennials, features 18 new paintings bursting with colour and layered in fabrics and objects in his version of Neo-Expressionism. Some have likened its anarchic exuberance to that of Jean-Michel Basquiat who he became close to in Paris and who persuaded him to move to New York.

To complement 1-54 and further enhance the city’s artistic reputation, The Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden also opens on February 24 with “L’Afrique n’est pas une Ile” (“Africa Is No Island”), an exhibition of work by 40 contemporary photographers capturing the continent’s traditions and spirituality and the individual’s families and their surroundings.

Highlights here include the images of Benin-based Ishola Akpo who explores his family history and Maïmouna Guerresi, whose strikingly beautiful cloaked figures The New Yorker magazine judged to be ‘mystical.’

More overtly political, an exposé of the scandal of waste and exploitation in Accra, Ghana, won Nyaba Léon Ouedraogo a runner up spot in the prestigious Prix Pictet photograph competition in 2012 for his series “The Hell of Copper.” In “The Phantoms of the River Congo” which was inspired by Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness set in the colonial era, he captures a compelling vision of the river today.

A reminder too of Africa’s history of colonial domination is reflected in the talks at the fair whose theme is “Always Decolonise!” which examines the perception that colonialism is not a historical event which is over and done with but needs constant evaluation and action.

As El Glaoui says: “We are still dealing with a lot of history and its impact on what is happening to day. It is not just about those who lived through colonial times but all this history, the past, has a subtle effect on people today — the way the country is structured, the way the government is structured, go back to colonial times so even if people have not experienced those days they will be aware of them.

“It shows itself in what might seem small ways. For example one of our artists finds it hard to travel because there is a lack of infrastructure, there is no consulate and it is difficult to get a visa. That’s a residue of colonial times.”

As Sulger-Buel says: “In their ways the artists I am showing are children of decolonisation whether they lived through it or born after but the challenge for Africans today is to survive in an African city.”

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London.

1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair will be held at the La Mamounia hotel in Marrakech on February 24 and 25.