Everyone knows that Vincent van Gogh cut off his left ear. But since that fateful event nearly 128 years ago, there has been continuing debate among scholars about the severity of that mutilation, which took place in Arles, France, in December 1888. Did he simply slice off a little chunk of his ear, or did he lop off the entire lobe?

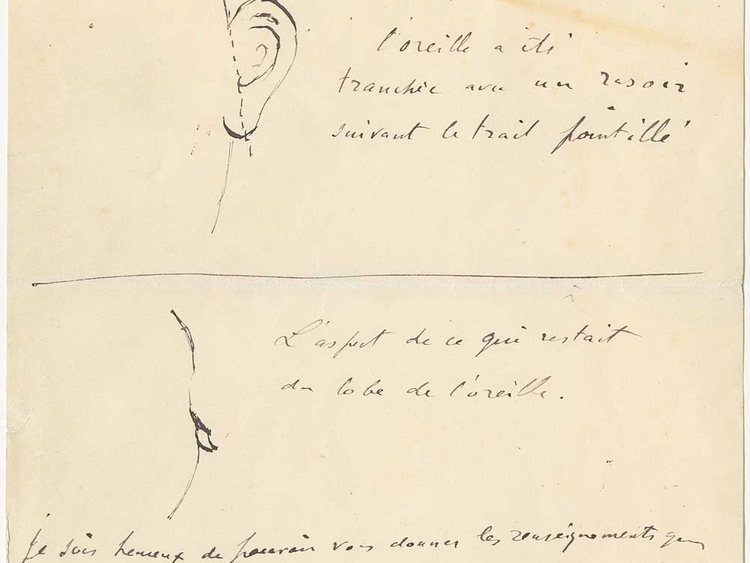

Author and amateur historian Bernadette Murphy, while researching the last period of that Dutch Post Impressionist’s life for a new book, discovered a document in an American archive that may help resolve the issue. A note written by Felix Rey, a doctor who treated van Gogh at the Arles hospital, contains a drawing of the mangled ear showing that the artist indeed cut off the whole thing.

The letter and drawing will be displayed for the first time at the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition “On the Verge of Insanity” along with previously unexhibited documents and artefacts that try to provide more detailed evidence about van Gogh’s mental illness.

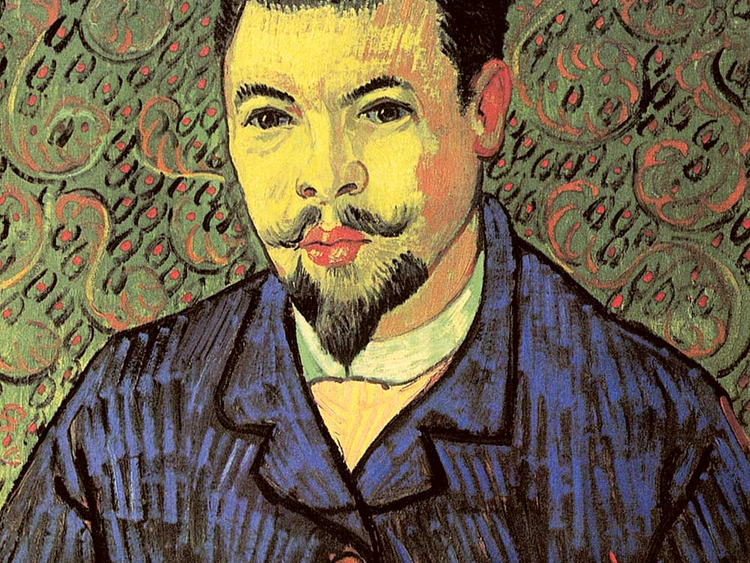

Portrait of Dr Felix Rey by Vincent van Gogh, 1889

The exhibition will also include about 25 paintings and other objects, such as a corroded revolver that van Gogh may have used to kill himself, museum officials say. These will try to explore, in particular, the final stretch of his life while his troubles escalated, from the ear-cutting incident to July 29, 1890, when he apparently committed suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise, France.

The subject of the artist’s mental state has always fascinated people who admire his art, but until now the Van Gogh Museum, which contains the largest collection of his work in the world, has not directly addressed the subject. Until recently, the museum has focused on van Gogh’s aesthetic and technical progression, but interest in his biography is driving a different approach to exhibitions.

“This is really the start of a new series of small, focused exhibitions, which will only take one floor of the building but will enable us to give the visitors more information about van Gogh’s life,” said Nienke Bakker, curator of paintings for the Van Gogh Museum and curator of this exhibition. “This seemed for us to be the perfect subject to start with.”

Bakker said that most museum visitors wanted to know the details of van Gogh’s life: “The three most frequently asked questions are: What happened with his ear? What kind of illness did he have? and, Why did he commit suicide?”

A sketch and notes by Dr Felix Rey who treated van Gogh AP

The exhibition coincides with the release of the book, “Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story”, by Murphy.

Steven Naifeh, an American historian who co-authored the 2011 “Van Gogh: The Life”, with Gregory White Smith said in an e-mail after looking at the new document, “I was willing to give them the benefit of the doubt, that they had indeed found new information from Rey, but it is not new, and it is not credible.”

In his biography, Naifeh argues that witnesses who saw van Gogh after Rey, including his brother Theo’s wife, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, the artist Paul Signac and van Gogh’s doctor in Auvers-sur-Oise, Dr Paul Gachet, said that the entire ear was not missing.

They all “saw a portion of the mutilated ear remaining — so much, in fact, that, when Vincent was seen from face-on, the damage could go unnoticed,” Naifeh wrote. “Dr Gachet, who saw Vincent in Auvers in 1890, made a very detailed etching of the artist’s mutilated ear at that time showing that the entire pinna (outer portion) of the ear was not taken off, but the missing portion was more than just a lobe.”

Various reasons for van Gogh’s self-harm have been given in the past. In Paul Gauguin’s autobiographical novel, “Avant et Apres”, he describes a disagreement between him and van Gogh in Arles after Gauguin decided to leave. Gauguin wrote that van Gogh chased him with a razor until Gauguin stopped him, and then van Gogh went home and wounded himself.

In her research, Murphy, who was born in Ireland and has lived in Provence, just outside Arles, for many years, was also able to identify the woman to whom van Gogh gave his ear. She said her name was Gabrielle, a young maid who worked in a brothel. She suffered for many years, Murphy said, with being called a prostitute because of the contact with van Gogh. According to a local newspaper report, he told her, “Keep this object carefully,” and she immediately fainted.

“There’s something semi-religious to the way he offers a part of his body to repair a part of her body,” Murphy said at a preview of the exhibition. “She had a nasty scar on her body, and it’s as if he’s giving her fresh flesh.”

Bakker now says she thinks this was the delirious, unconscious behaviour that became characteristic of van Gogh’s series of mental breakdowns. Van Gogh had no recollection of the events surrounding the ear episode, and said his memories of his actions during breakdowns were usually vague. In the hospital after the ear episode, he was ashamed to learn what he had done, and immediately put himself in the care of Rey, the Arles doctor.

Van Gogh’s fame has always been linked to his complicated biography, and particularly to his madness.

“The fact that 5-year-old children know who Vincent van Gogh is is partly because of this mangling of his ear,” Naifeh said in a phone interview. “If you were going to cite just a few facts about his life, this would be one of them.”

Many have tried to guess what kind of mental illness van Gogh had. Some suppose he may have had temporal lobe epilepsy, which can lead to seizures, erratic behaviour and loss of consciousness, while others believe his symptoms were more similar to bipolar disorder. Murphy said she thought it might have been a combination of the two. During the exhibition, the museum will host a symposium with doctors weighing in on the matter.

“We’ve been studying all these diagnoses that have been put forward in the 126 years since his death,” Bakker said. “Of course, it’s very hard to diagnose a person who is dead and has been dead a long time. We know what the symptoms were, because he was describing them in his own letters. He says he has hallucinations, that he’s speaking incoherently, that he doesn’t know what he’s doing.”

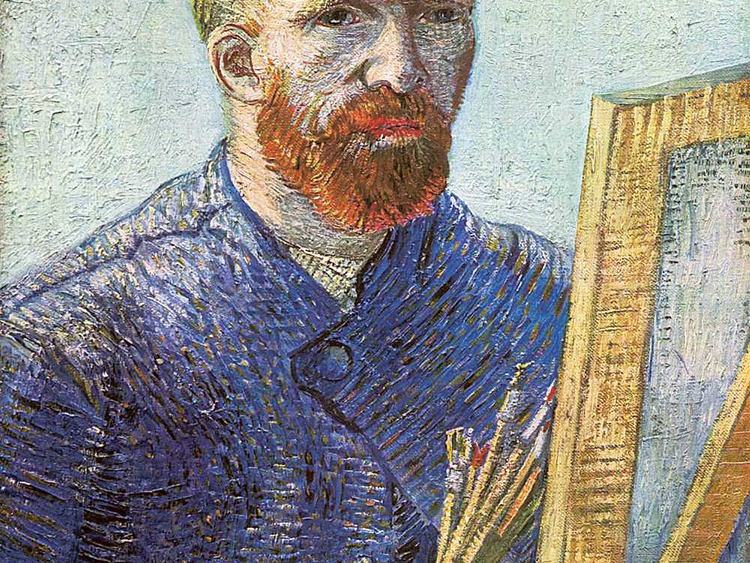

Exhibited for the first time are a police report on van Gogh’s incident in Arles, and a petition by van Gogh’s neighbours there in 1889, which asked the city’s mayor to institutionalise the artist. Rey’s letter and drawing of van Gogh’s severed ear will be displayed next to the artist’s portrait of Rey, painted in January 1889 and given to the doctor as thanks for his care.

The goal of the exhibition is not to link the artwork to his mental state but rather to make clear that van Gogh was struggling to work despite a debilitating illness.

“It’s not the case that he was having these hallucinations and painting them,” Bakker said. “A lot of people still think that. It’s amazing the amount of art he was able to create, especially considering that there were sometimes quite long periods when he wasn’t able to work.”

–New York Times News Service

“On the Verge of Insanity” runs at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until September 25.