The camera, a ubiquitous part of our life today, apparently got its name from the word Al Qumra coined by none other than the Arab scientist Al Hazen. Also known as Ibn Al Haytham, Al Hazen is credited with significant contributions to the invention of the pinhole camera, otherwise known as camera obscura, between AD1015 and 1021.

Thus it is appropriate for a museum dedicated to the moving image to take shape on Middle Eastern soil. Located in Tecom, the Dubai Moving Image Museum is the only of its kind in the region, the third in the world. Through the 300 unique artefacts on display visitors can experience the history of the moving image and all the incredible inventions that led to the advent of the cinema in the modern world.

At a time when the popularity of cinema is growing rapidly, most movie lovers are oblivious of its evolution and history. In the era of selfies and YouTube, visitors to the museum will get a remarkable insights into the gradual progression of visual entertainment from 1730s to the 20th century.

Featuring the private collection of Lebanon-born Bahrain national Akram Miknas, the museum is the culmination of his efforts that started nearly 40 years ago. “My idea simply was to share the history of film-making, the discoveries and the inventions that led to the films we watch today, with as many people as possible,” says Miknas, who is also chairman of Dubai-based Middle East Communication Network (MCN).

The journey through the museum begins with the play of shadows as the first example of moving images. It is said that cavemen used their hands and light to make shapes with shadows. Later, shadows were used artistically in storytelling and the art developed first in China and reached Europe in mid-18th century. The museum exhibits a few specimens of shadow theatre sets from 19th-century Germany and France. Metal figurines of people, horsemen and animals used in the shows presented against scenic backgrounds on paper are also preserved here.

“These shadow theatres sets were a form of popular entertainment for affluent families. Later, professional mechanical shadow sets were used in theatres. We have one such rare piece from a Parisian theatre dating 1860,” says museum manager Alizee Sarazin during a guided tour.

The museum is designed in a way that both adults and children will enjoy and understand the exhibits. All the artefacts are displayed chronologically according to concepts and inventions that contributed to the evolution of movies.

After shadow theatres came camera obscuras. They are an important development in the history of cinema as they eventually led to the birth of photography and the camera.

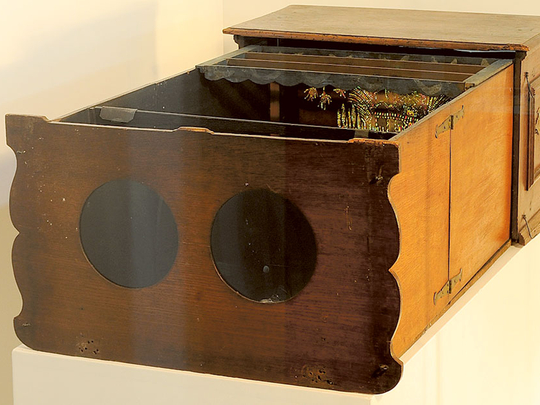

The camera obscura, a box with a tiny hole on one side, makes use of the law of optics. When rays of light pass through the box’s hole, they form an upside down image on the surface opposite the hole. Al Hazen wrote about this principle in his celebrated “Book of Optics”.

The combination of camera obscura, which only actually shows an inverted picture, and the property of silver nitrate led to the creation of the first photograph in 1827. The museum houses several such cameras, including some portable models from Russia and the United States.

The guided tour by Sarazin is peppered with interesting nuggets of information about each concept. Several of her visitors are school children brought to the museum as part of outside-the-classroom learning activities. “Children as young as five are able to enjoy and understand the exhibits,” she adds, wiping away tiny hand stains from the glass cabinet of a peep show box. These boxes were the next significant developments after camera obscuras.

In fact, the oldest piece in the museum is a Dutch peep show viewer dating back to 1750. This large box with image slides that can be viewed through a magnifying glass has images with small holes. When a source of light is placed behind these images, a day-and-night view is created.

“Across Europe showmen used to carry peep show boxes entertaining people at fairs and markets. Accompanied by musicians, they used to create stories and enthral viewers with scenes of battles, faraway lands and historical events,” says Sarazin.

In 1867, Carlo Ponti of Venice invented the megalethoscope, which took the peep show to another level. The megalethoscope had a large lens which created the optical illusion of depth and perspective when viewing photographs. It also used light to depict changes between day and night. The megalethoscope signified the early beginnings of 3D imagery.

At the museum visitors can see several versions of peep show boxes, megalethoscopes, zograscopes and stereoscopes. Both zograscope and stereoscope enhance the depth in illusion of images. “The stereoscope became very popular and several models were created. We have many hand-held models on display here. Through the 19th and 20th centuries as printing photographs became more affordable stereoscopes too gained popularity due to their ability to produce 3D images,” says Sarazin.

One of the impressive forms of stereoscopic entertainment, the Kaiserpanorama occupies centre stage at the museum. Invented by the German physicist August Fuhrmann in 1880, the Kaiserpanorama was typically placed in public spaces. This large machine allowed 12 people to view rotating slides with scenic images.

Yet another era in the world of images and visual entertainment began with the invention of magic lanterns in the late 17th century. An early form of image projectors, magic lanterns had pictures on sheets of glass and a concave mirror inside. With the use of a source of light, such as a candle or an oil lamp, the magic lantern artists wove tales around the scenes they showcased to their audiences.

“Magic lanterns were also in a way a social phenomenon as people gathered together to watch the shows. They were a precursor to cinema and film projectors,” says Sarazin. The 19th century saw an enormous development of lanterns for use in homes as ornate toys for children. Among several lanterns, the museum also houses a 1001 Nacht toy magic lantern from Germany. This lantern had hand-painted images on glass slides, which could be projected on a wall. Its top is in the shape of as a mosque and represents the popular Middle Eastern tales “One Thousand and One Nights”.

Animating and transforming images were the next important milestones that led to the birth of cinema. Thaumatropes, phenakistiscope and zoetropes were a series of innovations related to animation that later helped in developing cinema projectors. In 1877 Charles Emile Reynaud, a Frenchman, patented a new type of zoetrope using mirrors and called it the praxinoscope.

The praxinoscope has a spinning drum with a strip of pictures placed around its inner surface that also has a circle of mirrors in its centre. When a person spins the drum the reflection of the pictures in the mirror produces an illusion of motion.

“Walt Disney and the Lumiere brothers, who are credited as the first filmmakers, were inspired by the praxinoscope,” says Sarazin, as she gave a demonstration of a praxinoscope and a thaumatrope. The museum tour ends where cinema begins with the Lumiere brothers since the focus is on the story of its evolution.

All these items were collected by Miknas during his travels around the world. Only a part of his huge collection has been displayed in the museum. “The subject of the moving image and its related items are extremely difficult to find. There are very few collectors world over. We all buy and share from each other’s collections,” he says.

His passion for collecting unique items started as early as the age of 13 when he asked his father for a family owned antique tea set as a present. Later his interest in photography and his career in advertising led him to understand the importance of visual communication. It made him discover the origins of moving imagery.

“The most cherished item from my collection, which also happens to be the first one I bought, is the Kinora,” says Miknas. Kinora is a motion picture device that creates images from a reel of printed moving papers, similar to a flip book. It was difficult for Miknas to find reels for his “Kinora” and this search led him to unearth related antiques that eventually gave birth to a moving images collection.

A recipient of the Shaikh Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Patrons of the Arts award in 2013, Miknas is a visionary whose obsession with images is now making the public see cinema in a new light.

Tessy Koshy is an independent writer based in Dubai.