The National Museum at Janpath, in New Delhi, has opened a “jewellery gallery” called Alamkara (the beauty of ornament) that has hundreds of visitors trudging in to admire India’s traditional designs, which reflect its glorious past. While most foreign tourists gape at the glitter of the outstanding designs belonging to different states, Indians shriek with delight as they marvel at the creativity of the designers.

The museum has the country’s largest repository of jewels and the gallery can astound both fashion students and historians. The glittering pieces exhibited at the gallery offer a glimpse of India’s rich tradition in the decorative arts.

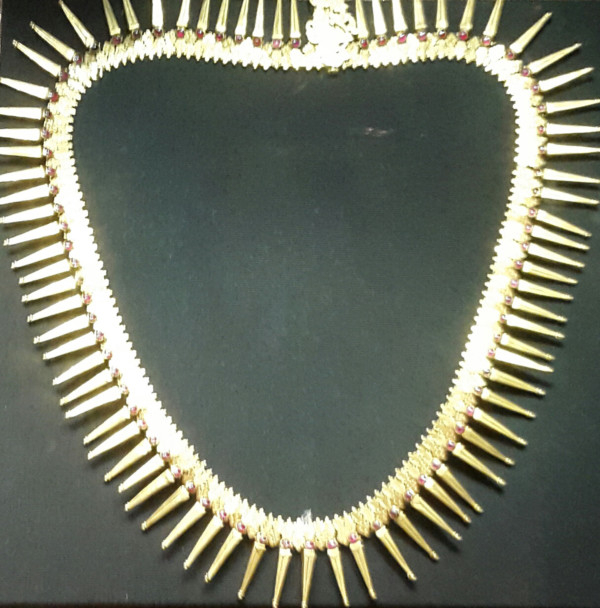

More than 250 items, displayed nuder 15 categories, convey the story of Indian jewellery — from the beautifully tumbled agate bead necklaces of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa to the fabulous jewels adorned with images of gods and goddesses. The collection spanning important periods in Indian history also has magnificent jewellery pieces that once formed a part of the treasures of the Mughal emperors and the maharajas.

Curated by Usha Balakrishnan, these include everyday wear items and grand creations made for ceremonial occasions. Strikingly stylized forms of the peasants and tribals’ jewellery vie with the extraordinary items that were made for the rich and the famous.

From items fashioned from shell, ivory, bone and silver to those made from gold and encrusted with gemstones and from pieces made to adorn, enhance and beautify to those worn to protect, heal and energise, the jewels of India are a lesson in Indian aesthetics.

A museum official said, “For more than 2,000 years, India was the sole supplier of gemstones to the world. Golconda diamonds were coveted and drew merchants across land and sea routes to India. Emeralds from Colombia, rubies and spinels from Burma and Sri Lanka, sapphires from Kashmir and pearls from the Gulf of Manar and Bahrain, poured into gem bazaars scattered across the length and breadth of the country. That’s why India was at that time known as the Golden Bird.”

However, the small number of jewels that have survived from different periods and different parts of the country provide evidence of a tradition without any parallel in the world. Interestingly, the items kept in glass cases, are open to be photographed, enabling some visitors to click and rush to the jeweller with their choice of piece to be reproduced.

Jewels from the Indus Valley Civilisation and Sirkap in Taxila are two of the most intriguing categories in the collection. These are the oldest pieces found anywhere in India.

“Excavations carried out in Mohenjo-daro, Harappa and other cities had reportedly brought a treasure trove of jewellery, which is now exhibited in the gallery. The ornaments were usually made of gold, bones or stones. Though these materials are chemically inert and last for thousands of years, the conservation department of the Museum has made special efforts to ensure they do not get damaged,” the official briefed.

A sophisticated bead-making industry existed in olden times, which is evident in the incredible variety of raw material, knowledge of metallurgy, technology of fabrication and range of forms and styles that existed more than 4000 years ago.

The exhibition begins from pieces relating to the Indus Valley Civilisation. The necklace of steatite and gold beads is capped with gold on both sides. It has three pendants of banded agate beads decorated with bright red bands in the middle with five pendants of jade beads on one side and four pendants of jade beads on the other.

Then there’s the flat gold brooch formed from three thick gold wires laid on a sheet of silver and bent to form concentric rows in the form of the figure 8. The spaces in between the wires are inlaid with tiny cylindrical steatite beads having gold ends.

The Sirkap jewels are distinguished by imaginative designs, rich decorative details and intricate craftsmanship. Quite prominent are the gold, orthoclase and feldspar hairpins from 1st century CE Sirkap.

Sirkap, in the Punjab province of Pakistan, was the capital city of the Bactrian Greeks. In the early 20th century, British archeologist Sir John Marshall excavated the site and discovered a well laid out city and unearthed a huge collection of gold jewellery. The jewels of Sirkap are Indo-Greek — classically Greco-Roman in design and workmanship, but manifest elements of indigenous idioms.

There are also some fabulous earrings crafted from sheet gold and decorated with micro-granules, no larger than grains of sand, and elaborate neck pieces decorated with wire and arranged in floral designs inlaid with coloured stones and turquoise paste. Strikingly sophisticated bangles and bracelets too are crafted from sheet gold.

The official remarked, “From the jewels, it is evident that the people of Sirkap decorated their hair with fillets and pins, wrapped elaborate girdles of rows of fish around their waist and adorned their fingers with exquisitely crafted rings.”

The section has a beautiful gold bracelet from 1st century CE and the earrings combine sheet gold and granulation of crescent. The piece is hollow, with an inverted bud-shaped pendant suspended from it and attached to a ring embossed with gold granules. The hollow crescent forms are filled with a solid lac or pitch.

Other interesting sections include the Mughal heritage, amulets and marriage pendants. The jewellery from the Mughal period is a unique combination of metals, gemstones and polychrome metal. While amulets were believed to ward off the evil eye, tiger claws and elephant tusks were fashioned into ornaments, symbolising power.

The Sartorial Splendour category includes ornaments once owned by the maharajas. And many of the earliest pieces were donated to the museum by kings. “The 19th century was a period of magnificent splendour and ostentatious display in the native courts that were scattered around India. Maharajas, nawabs and the nizams emulated the style of the Mughal emperors and jewels were quintessential accessories to court life and aristocratic privilege,” the museum official informed.

The attire of maharajas was a mixture of traditional and modern, Indian and Western. They wore Indian turbans and decorated them with diamonds and jewels or with European tiaras and hairpins. Most of them wore heavily embroidered Western style jackets, over which they tied beautiful armbands and hung elaborate necklaces around the neck. The ornaments were a way to display power and wealth and also made a style statement, he added.

The gods and goddesses category reflects the custom of idol worship prevalent in several parts of India. Ornaments include mukuts (head gear), inspired from temple bells, featuring popular gods and goddesses on necklaces and headgears.

Another section termed Head To Toe depicts how women adorned themselves with jewels from top to toes. Jewels were accessories of allure; they functioned as symbols of marital status, were an insurance against hard times and served as protective talismans. The section features necklaces such as Kolhapur’s thushi, Rajasthan’s timania and hansli; hair accessories from South India — tika from Punjab and Rajasthan, choti and borla from Rajasthan, jhumar from Lucknow, chak from Himachal Pradesh, jadavihu from Karnataka; and bangles from various parts of India.

Also included is a super-sized gold mangalsutra from the 19th century Chettinad and a one-diamond enamel and pearl encrusted neckpiece from Rajasthan. Then there are the more delicately crafted pieces that still appeal across the ages, including the gold, white sapphire and pearl nose rings from 19th-century Maharashtra, and the pearl, diamond and gold jhumar from late 19th-century Lucknow.

Several other pieces of artistic significance find a place in the gallery, which disseminates knowledge about the significance of the jewellery items in respect of history, culture and artistic excellence and achievements of Indian craftsmen.

The National Museum, as it is seen today, has an interesting beginning. The blueprint for establishing it in Delhi was prepared by the Maurice Gwyer Committee in 1946. An exhibition of Indian art, consisting of selected artefacts from various museums of India was organised by the Royal Academy, London, with the cooperation of the Government of India and Britain. The exhibition went on display in the galleries of Burlington House, London, during 1947-1948.

It was then decided to display the same collection in Delhi, before the return of exhibits to their respective museums. Thereafter, in 1949, an exhibition was organised at the President’s House. It proved a huge success and led to the creation of the National Museum. Taking a cue from exhibits at other museums, advantage was taken of the magnificent collection to build up the nucleus collection of the museum.

While the museum continued to grow its collection through gifts that were sought painstakingly, artefacts were collected through its Arts Purchase Committee. The Museum at present holds approximately 2,00,000 objects of diverse nature and its holdings cover a time span of more than five thousand years of Indian cultural heritage.

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.