Marina Abramovic is on a Skype call from Madrid, showing off her custom-made red sweater, which says “Love conquers all.”

“I’ve been wearing it all the time,” she says in her husky, Serbian accent. “It’s like my pyjamas.”

This lighter side of Abramovic — a Skype pyjama party from Spain — is not what we’re used to seeing from the trailblazing performance artist. Now, an even different version of her is on view in a solo show at the Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. Early Works features 12 historical performances from 1970 to 1975 — a time when the now multimillionaire artist was penniless and living out of a car with a backpack full of film negatives.

“I lived in cars and trucks, I’m amazed the negatives survived,” said Abramovic, who recently turned 71-years-old. “To appreciate the present, we should really look to the past.”

Female artists had a tough time breaking into the art world in the 1970s, when performance art wasn’t taken seriously by a male-dominated majority. “I have a 50 year career right now and for the past 40 years, performance art wasn’t considered art,” said Abramovic. “I had incredible trust in my own intuition to survive and I believed in performance art so strongly. You can never give up, but when you don’t give up for 50 years? Wow, that’s a long stretch. I never stopped working.”

Abramovic, whose collaborators include Jay-Z and Lady Gaga, had her acclaimed Museum of Modern Art retrospective, The Artist is Present, where she sat in the museum for over 700 hours, in 2010. Her recent retrospective at the Louisiana Museum in Denmark called The Cleaner was about cleaning past memories, while those same memories have been rehashed in her recent memoir, Walk Through Walls.

But 40 years ago, she was just a struggling artist on the European festival circuit getting ripped off by galleries who still haven’t paid her.

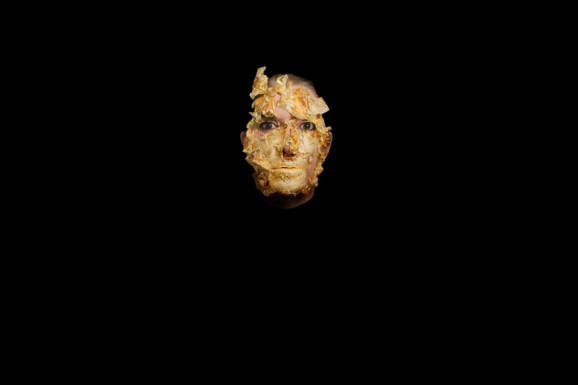

Her art from that time reflects her struggle. In this exhibition, some of the early performance pieces on view include Lips of Thomas, where she cuts a five-pointed star on her stomach with a razor blade, then whips herself and lies down on a cross made of ice blocks.

Another piece is Rhythm 0, where Abramovic placed 72 objects on a table — including a loaded gun and razor blades — and invited the audience to do as they please with her. They cut her clothes off with razor blades, touched her intimately, slashed her throat, sucked her blood and pointed the gun to her head with her own finger on the trigger.

“It was related to the idea of how far the public can go, whether they will kill the performer or not,” she said. “I really think they can.”

It wasn’t about being taken advantage of as a woman, says the artist. “I never take the gender into consideration for the artwork,” she said. “Art doesn’t have a gender — there are only two categories to me, good art and bad art.”

But with the #MeToo movement and the sexual assault allegations against Harvey Weinstein, sexual misconduct and harassment allegations have surfaced in the art world, from Artforum magazine publisher Knight Landesman to New York artist Chuck Close and photographers Mario Testino and Bruce Weber.

“I think it’s terrible and it’s so sad these people didn’t have the courage to say something in the moment when it was happening,” said Abramovic. “I would not wait 20 years to say such a thing. If I could say something to all these people, don’t wait. It’s very important to have courage in your life; otherwise you have a supressed life, which is terrible.”

While her own performance work is linked with shamanistic rituals, the far right have misunderstood her art as Satanism. Her work surfaced during the Pizzagate scandal of 2016, where one of Abramovicc’s emails to Democratic lobbyist Tony Podesta (brother of Hillary Clinton campaign chair John Podesta) refers to a “Spirit Cooking”, which is the name of an artwork she made in 1996. It was assumed to be an occult ritual.

“People can so easily put labels, we are afraid of everything,” she said. “I talk openly on every single subject in my work, it’s very important to understand it and put it in the right context.”

One spiritual leader she does admire is the Dalai Lama, whose lectures have taught her to forgive. “It’s the only way we can stop the wars in the world,” she said, “if we learn to forgive.”

But looking back on her old self, the Abramovic of the 1970s, she sees someone totally different. “I look back and think ‘wow, this kid had a really big vision,’ bigger than I have now,” she said. “I don’t look back much but I try to connect points to answer the same question, ‘what is my function in this world?’”

It ties into the Abramovic Method, a series of meditative exercises she created, which attempts to test physical agility and answer philosophical questions around life and death. “I am not interested in small questions,” she says. “The Dalai Lama helped me so much.”

Serendipity also helped out, apparently, as it helped her forgive her former creative collaborator and romantic partner Ulay (born Frank Uwe Laysiepen), who she split with in 1988. He sued Abramovic in 2015 for $300,000 for art sales of their co-authored artworks and won. Unexpectedly, the artists found each other in India at a month-long artist’s retreat last year.

“It was so important for us that we really became friends and I learned the forgiveness,” she said. “All this [expletive], it was a learning process and we made important work and this is all that matters.”

Now, Abramovic and Ulay are good friends who text each other every day. “All the hate is gone,” she said. “I’ve never been there.”

Even at 71, she doesn’t show any signs of slowing down. “I am still performing,” she said. “It’s crazy because my generation is gone.”

With an exhibition schedule booked to 2024, she is working on new artwork for a solo show at the Royal Academy of Art in London in 2020. In the meantime, she is maintaining her roving project, the Marina Abramovic Institute, which hosts temporary projects across the globe.

But not without controversy. The plan was to build an institute in a converted theatre in Hudson, New York, which would be designed by architect Rem Koolhaas. But after crowdfunding $660,000 on Kickstarter — and refusing to return the funds to the backers, though they each got their promised pledge rewards — she backed out of the plan, as building costs were estimated at $31 million.

“I don’t want to spend the time to fundraise because it’s more important to make projects around the world,” said Abramovic. “More than a million people are participating at my institute and this is our function, the institute is alive more than ever but not based to one building.”

Since its conception, the institute has travelled to Athens, Kiev and Sao Paulo. It will visit for the inaugural Bangkok Biennial later this year.

From an artist who has cut herself and made videos where she has screamed for hours, one wouldn’t expect Abramovic to be so focused on love. But after confronting her fears, her approach has changed.

“You know what?” asks Abramovic in her red pyjamas. “In life, honestly, love is the first thing. Not to just love the work but to love yourself, and the moment you’re in love — the world is such a great place.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Marina Abramovic: Early Works is at Sean Kelly gallery, New York, until March 17.