If you are standing in a cinema foyer and see a group of people filing out of a screening while wringing invisible moisture from their hands and sniffing their clothing uneasily, chances are they have been watching a David Fincher film. Fincher’s work doesn’t just stay with you. It clings.

In “Seven”, two detectives wander a nameless, rain-lashed city while a serial killer slips through the shadows, 15 steps ahead. In “The Social Network”, a brilliant young misanthrope builds walls around himself, first emotional, then digital, and finally legal, until he finds himself trapped in a gated community of one.

“Zodiac”, Fincher’s masterpiece, features another serial killer, although the film is not about the sudden, violent snuffing-out of life so much as the slow, creeping loss of it to nightmares and obsessions.

Darkness in Fincher is a palpable, animal presence, with its own warmth and weight and stink. To call it another character in the film is to sell it short. It sits next to you in the cinema, its wet breath fluttering on your cheek.

Perhaps Fincher’s defining skill is the deftness with which he balances the competing interests of the corrosive and the commercial. He makes big, Friday-night films, but each one is laced with Monday-morning dread. To find his equal in that regard, you have to look back to Alfred Hitchcock and Otto Preminger — although even the directors of “Frenzy” and “Laura” might have balked at the exhilarated malice of “Seven”. As a child, two experiences were responsible for placing a camera in his hands, though neither explains the source of the winter chill that runs through his work.

Aged 7, he watched “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”, and realised that making films could be fun. Aged 12, he was aware that the man who lived down the road from his family in Marin County, California, was George Lucas, the director of “American Graffiti”, and realised that making films was within reach. At 18, he took a job with Lucas at his special effects company, Industrial Light & Magic, and worked as an effects technician on “Return of the Jedi”.

Perhaps inevitably, the Imperial Walker that shoots an Ewok dead was his. From Lucasfilm, Fincher joined the Eighties music-video gold rush, and has made 55 to date, the majority of them between 1984 and 1990. His two most famous, both made with Madonna, were drenched in vintage cinema. “Express Yourself” (1989) peoples Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” with Tom of Finland beefcakes, while “Vogue” (1990) recreated classic publicity portraits of Golden Age beauties such as Katharine Hepburn, Veronica Lake and Greta Garbo. He liked the work because it allowed him to hone his craft in relative anonymity: budgets were generous and anything was possible, but when a video turned out badly, blame was generally apportioned to the act.

In the early Nineties, during the making of his first feature, “Alien 3”, Fincher became the act. Fox approached him to direct in 1991, with $7 million (Dh26 million) of the budget already spent. He was a 28-year-old rising star, and, he soon suspected, one of the few people on set to care that the film wasn’t simply a commercial success, but an artistic one. He micromanaged every aspect of the production, pushed back against every compromise, and drove the studio half-mad. One of the producers, David Giler, who had seemingly been unmoved by Fincher’s recent work for Nike and adidas, called him, among other things, “a shoe salesman”. “Alien 3” made money, but was mostly unloved, and Fincher went back to selling shoes — until, almost two years later, the script for a biblically themed serial-killer film called “Seven” arrived in the post. It was an old draft — one with an unwatchably bleak and long-since rewritten finale, in which a mysterious box is delivered to its young detective hero in the middle of the desert — but Fincher liked what he read, and New Line gave him $33 million to make the film. He only had one proviso. He was going to make it with the old ending.

Almost 20 years after opening the box, Fincher is thriving. He is 52 years old, and wears a tailored jacket and smart dark jeans. His eyes are small, blue and boyish, and a silver goatee adds gravitas. His tenth film, an adaptation of the bestselling thriller novel “Gone Girl”, had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival last month. “Gone Girl” has allowed this great technician of darkness a chance to lighten up, within acceptable parameters, which means it is a film that wants to show you the best bad time it can whip up.

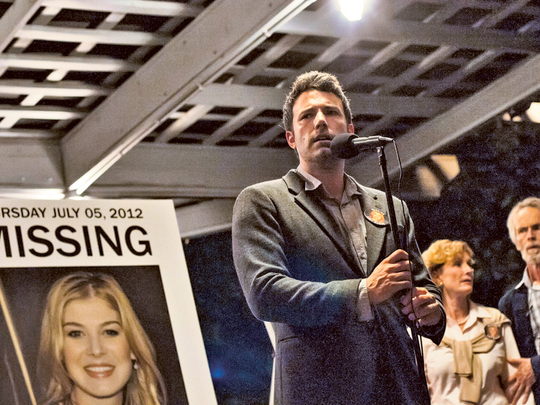

It was adapted by Gillian Flynn, the writer of the original novel, and stars Rosamund Pike and Ben Affleck as Amy and Nick Dunne, two married writers whose relationship, which began in a blaze of romance, is now hopelessly bogged down in bitterness. When Amy goes missing, the police start eyeing Nick with suspicion, and we, along with the TV news crews that descend on the town, soon realise he has something to hide. “This is the kind of stuff it’s very hard to make a cinema audience engage with,” says Fincher, sadly shaking his head, “because we’ve got this whole ‘likeability’ thing that people are so concerned with. They reserve their empathy because they don’t want to fall in love with someone whose body is going to end up in a 50-gallon oil drum. They don’t want to be charmed by someone who might have hacked his wife up and put her in the crawl space.”

In a Fincher film, both outcomes are highly possible. I ask him who the hero of “Gone Girl” is, and he looks momentarily confused, as if I’m trying to catch him out. “No one,” he says. There was no pressing need for Fincher to make another film in which police scrub blood from kitchen floors, but the appeal of “Gone Girl”, as he saw it, ran deeper than that.

“The thing in this story that I had never seen articulated before,” he says, “was this idea that we create these narcissistic projections of ourselves in order to get people to like us, and in some cases to seduce them. And yet we remain completely oblivious that other people are doing the same thing to us.”

Sure enough, the early stages of the couple’s courtship are seen in luxurious flashback, and like many Fincher pictures, these scenes slip past with the silken menace of a bad dream. In “The Game”, Michael Douglas plays an investment banker who participates, somewhat reluctantly, in a role-play exercise that puts his career and, later, his safety at risk. Masked gunmen chase him down wet alleys, and the danger is somehow both true and false at once. “The Game” is a film about the ontological con-job of filmmaking: it is Synecdoche, New York, with nachos and a jumbo Coke. Then came “Fight Club”, a film narrated by a chronic insomniac who can barely tell the difference between what is inside his head and out of it: his mentor, Tyler Durden, once worked in a cinema projection booth, splicing single frames of pornography into family films, and we are invited to wonder if he might be projecting the very film we are watching.

Adapting “Fight Club” from Chuck Palahniuk’s novel appealed to Fincher “because I couldn’t work out how to make the movie,” he shrugs. “When I was reading the book I was in tears, because the same person that had been talking in my dreams and telling me to do things had now written a novel.”

The breakthrough was packing all of the book’s fury and scorn into a voice-over, which was pre-recorded by Edward Norton and played back on set, ensuring the cast’s performances were in sync to the nearest millisecond. “I kept telling the studio, ‘It has to be like the internet, with pop-up windows,’” he says. “Here’s what you need to know: shew, shew, shew” — he mimes lines whistling past his ears like daggers — “and here’s how fast you need to know it.” “Fight Club” premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1999, where Fincher realised his voice-over brainwave had a downside.

“When we saw the Italian subtitles for the first time, you could barely see the people behind them,” he says. “There were paragraphs and paragraphs. I flipped out and I told my wife, ‘We’re doomed.’ It looked like some kind of graphic art project.” As things turned out, this was the least of his concerns: “Fight Club” was a controversy bomb, albeit one that almost no one went to see. (In cinemas, at least: it later found an enormous, appreciative audience on DVD.)

Many critics were outraged — writing in the London Evening Standard, Alexander Walker called it “an inadmissible assault on personal decency” and “a paradigm of the Hitler state” — while Fox marketed the film primarily to fans of premium cable wrestling; a move not unlike plastering Wall Street with posters for “American Psycho”.

After “Fight Club” came something simpler: “Panic Room”, a claustrophobic thriller in which a mother and daughter, played by Jodie Foster and Kristen Stewart, take refuge from three burglars in a reinforced security chamber. Fincher took on the project partly because someone advised him not to but also because he had not yet made a film in which the characters and viewers were in lock-step. “I’d made three movies where the narrative was ahead of the audience, and everything was revealed in the end,” he says. “But I’d never made something with the ‘Oh no! Don’t open the door!’ kind of dramatic irony. So I wanted to try that.”

Scanning her bank of security monitors, Foster’s character was like a modern-day Jimmy Stewart in “Rear Window” — and in Fincher’s films, the camera mostly hangs back, a passive observer rather than active participant. He is notorious among actors for insisting on take after take after take: Stellan Skarsgard, who worked with Fincher on “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo”, described the process thus: “any pretension and preparation you’ve done, all the square, intellectual work, you can’t keep that up for 40 takes. It breaks down, and new things start popping up ... that’s when the film comes alive.”

The opening scene of “The Social Network”, Fincher’s brilliant, Oscar-winning drama about the invention of Facebook, was shot in 99 takes, and the final version was assembled from snippets, some just a syllable in length, from almost all of them. Watch it again and you realise just how much care has been taken over its construction: the background noise of the bar is turned up just too loud, so that we, like Erica Albright, have to crane in to keep pace with Mark Zuckerberg’s runaway train of thought.

Fincher had been underwhelmed by the experience of making “Panic Room”, and five years passed before he released another film: then he made four on the hoof, at a rate of one per year, as well as producing and directing episodes of the television drama “House of Cards”. “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button”, “The Social Network” and “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” showed off his range — a magic-realist epic, a state-of-the-nation drama and a gourmet potboiler. But it was “Zodiac”, his 2007 comeback film, that proved his mastery.

The film is a scrupulous recounting of the real-life manhunt for the Zodiac serial killer in San Francisco in the Sixties and Seventies. It may also be Fincher’s most personal. One of the director’s earliest memories was travelling to school with a police escort in 1969, when he was 7 years old. In a letter to the San Francisco Chronicle, the killer had threatened to target a school bus: “Just shoot out the frunt tire [sic] + then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out,” he wrote.

“Zodiac” is perhaps the great Seventies paranoid thriller: the fact it was made 30 years after its contemporaries — the likes of “All the President’s Men” and “The Parallax View” — is neither here nor there. It centres on three men, Jake Gyllenhaal’s amateur sleuth, Robert Downey Jr’s newspaper reporter and Mark Ruffalo’s police detective, each of whom sets out to unmask the killer.

Over 158 minutes, the years, clues and suspects tumble past. But we know from history that Zodiac was never caught: “closure”, an entirely un-Fincheresque concept, is not, and could never be, on the table. Instead, the men are swallowed by the quest, and life, as in “The Game”, becomes a perpetual nightmare from which they can’t jolt themselves awake. The deliberate denial of satisfaction — a technique Fincher also uses to delicious, albeit less profound, effect in “Gone Girl” — is precisely what keeps his films rolling around your head long after they end. And it is clearly a point of personal pride: as soon as I say the word “unsatisfying”, he rubs his hands together gleefully. “Where’s my satisfaction? Where’s my satisfaction?” he says in a fake-panicked tone, looking under his chair and behind a cushion. Then he chuckles. “You know I don’t try to p*** people off, right?” Fincher says. “It’s just always been the right thing to do.”

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2014