For more than three decades, a home in Gurugram — a city in the Indian state of Haryana — has housed a priceless, yet little-known collection of Indian tribal and folk art. The collection is the work of painter and art historian Kishan Chand Aryan. A great visionary, he foresaw long ago the fate these artefacts would meet and began preserving them for posterity. Many of the objects are now extinct. Some in the collection are nearly 2500 years old! This one-man collection, comprising countless artefacts, is being taken care of by his son Baij Nath Aryan and daughter Subhasini Aryan, after the death of Aryan in 2002.

Every corner and wall space of the rooms in the artistically designed house is crammed with artefacts — precious, old and of exquisite craftsmanship. The place is called Museum of Folk, Tribal & Neglected Art. Baij Nath explains the ‘neglected’ part in the name of the museum. “When my father began collecting and preserving artefacts, many objects did not receive proper attention or place of respect by any museum, collector or art connoisseurs. Hence the word ‘neglected’. Also, numerous items are not being created anymore and their traditions have become extinct. These can now be seen only in our museum,” he says.

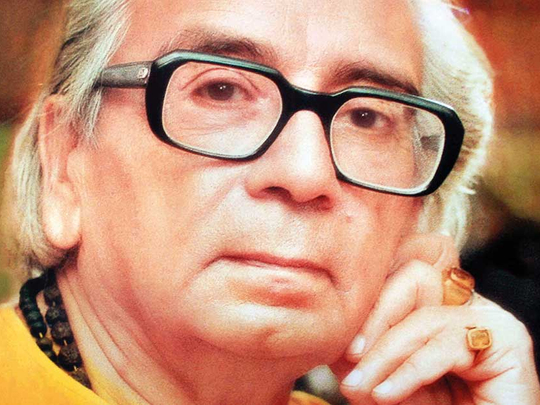

Born in Amritsar into a family of painters in 1919, Aryan was not only a painter, but also an accomplished sculptor, calligrapher, illustrator and art collector. His father Lala Harnam Dass was a well-known painter and Aryan was greatly influenced by his work. As a child, Aryan would spend hours sitting next to him dabbing colours on bits of paper. Exposed to various kinds of art forms, he carved out a niche for himself, even though his father dissuaded him from following a profession that would indulge his passion but leave him penniless. Sans any formal training, he mastered the skills and techniques merely by observation and practice.

Baij Nath says, “At the young age of 20, my father was the first person in undivided India to introduce book jacket illustrations when photography was not in vogue. Around the same time, he was gripped with a strong urge to salvage the artworks for posterity and wished to accord them the status they deserved. This happened after he noticed the gradual disappearance of many ordinary-looking, but very important from historical and aesthetic point of view, everyday objects from Indus Valley Civilisation.”

In the early 1940s, he travelled extensively to the remotest parts of India, especially the regions of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan, to collect countless photographs of art and craft objects including mud wall paintings, temple murals, wood carvings, toys, pottery and jewellery. His drew the attention of art aficionados to the ‘bazaar school’ of paintings from Punjab. These can now be seen only in museums in London or in the Aryans’ collection. He had realised that the millennia-old folk and tribal tradition would not last long as it was already in a miserable condition.

“My father witnessed charkhas and wood carvings being used for burning, exquisite embroideries converted into rags and vibrant folk bronzes being reshaped into door handles. Sensing that in the coming few decades there would be no trace or record of such artwork, he began on a rescue mission. Each piece was handpicked by him with a different perspective,” Baij Nath says

After the Partition of India in 1947, Aryan migrated to India along with his wife and two children, from Lahore, Pakistan. “Using his imagination, my father had painted the horrors of incidents that took place in Thohakhalsa, near Rawalpindi and the British forces were after him. He had to flee overnight and reached Himachal Pradesh, where he hid for over a year. Later, he shifted to Old Delhi. Painting was his hobby and profession and he became a renowned modern painter of the country,” Baij Nath recalls.

“He travelled in Europe and the Middle East in 1958 and it resulted in experimentation in diverse media and pioneering work in collages, mesh-wire and metal assemblages. In 1963, an associate of Le Corbusier, upon seeing my father’s work commented, ‘Indians will not be able to understand it for another 50 years!’ But as things stand today, even now people are unable to comprehend the works he undertook,” he adds.

In 1964, Aryan was awarded the Lalit Kala Akademi National Award. In 1966, he moved into a rented apartment in Greater Kailash, which back then was not considered a posh neighbourhood in New Delhi. He had already abandoned his art practice to systematically preserve, promote and disseminate Indian folk, tribal and neglected arts and wrote 23 scholarly books and started documenting and segregating his vast collection in order to eventually set up a museum, which can be considered the finest in the world.

“However, the sad fact is that even though not many Indians are aware of the existence of this private museum, ambassadors and diplomats often visit the place, which is known to them through word-of-mouth. The collection is so diverse, comprehensive and large that more than half-a-dozen dedicated museums can be built to showcase the items. Unfortunately, we do not have the resources to build even one museum at a centrally located place for the benefit of art connoisseurs,” he rues.

Aryan amassed rare and mostly extinct folk, tribal and neglected objects d’art, including vast number of images of the Hindu deity Hanuman. In fact, the Hanuman images are found in all mediums — from fragile paper to invincible bronze. Collected from all over India, Nepal and South-East Asia, it is probably the largest in the world. A figurine of the Mother Goddess is datable to the 4th century BC and some bronze icons of Hindu deities go back to the 10th century AD, but many do not go beyond the early 18th century and wide numbers of artefacts have no history.

Despite the dearth of space and lack of financial resources, Aryan spent all his time, energy and money in building the enormous collection. Based on his experiences and collection, he wrote many books, including: Folk Bronzes of North Western India, Cultural Heritage of Punjab and Hanuman in Art and Mythology.

In one of his books, Aryan wrote: “Had it not been for these artisans living and working in the rural and tribal pockets, our precious artistic and cultural heritage would not have survived. The dynastic or courtly arts relied upon royal patronage, and lasted as long as the political fortunes of the rajas ebbed and flowed, the rural and tribal art forms continued to be shaped by the artisans in an unbroken continuity, flowing on and on unhindered like a stream. The peaceful living conditions in the rural and tribal pockets remained unaffected by the political upheavals and invasions. Besides, the rural tribal craftsmen enjoyed complete social-economic security.”

Aryan moved to Gurugram in 1984 and set up the museum at his 500 square yard residence. On entering, one finds a wooden marriage post from Bastar in Chhattisgarh. A brown wooden door, engraved with folk motifs and designed by Aryan in collaboration with a Rajasthani artist, leads to the next room, wherein a temple door from Himachal Pradesh is placed prominently. Baij Nath points out that several such important pieces were simply left in villages and towns, with no one to value or take care of the items.

The collection of mukhalingas occupies a large portion of one of the floors of the two-storeyed house. Hundreds of statuettes and toys are stored in glass-paned panels on the staircase and in the rooms. There’s no end to the wonders in the house of the Aryans. Overflowing with works of art, even a bathroom is used to stack catalogues and research material.

It is a rich repertoire of the rare folk bronzes, tribal wood carvings, functional iron artefacts from various socio-cultural locales, antique terracotta figurines and toys, myriad schools of folk and bazaar paintings, rare book covers and fabulous folk embroideries from Himachal Pradesh. Exquisite Punjab phulkaris, pahari rumals from Himachal Pradesh, kanthas from Bengal and rare Swat shawls together with a plethora of folk textiles from other regions. The lithographs from Amritsar dating from the early British period are other unique feature — the only other such pieces are found in the Archer Collection at Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The collection also includes various ritualistic and religious art objects like tantric drawings and yantras, patakas depicting devis and yoginis — the only one of their kind preserved in any museum. Then there are some stunning pataka paintings from Jodhpur, Rajasthan. The priests, for their ritual use, painted these. Other items include silver pendants, armlets, stone images, metal horns, dramatic masks of various shapes and sizes, a large collection of life-size Shiva heads or Mukjalingams from Karnataka, originally used as phallic covers, Bhuta images from South Karnataka and an imposing collection of Durga Mahishasura mardinis. Amongst other highlights are Ganjifa, the traditional playing cards and the exquisitely worked card puppets — the only ones of the type from the 17th century Jaisalmer, Rajasthan.

Baij Nath says, “The most enterprising aspect of the museum is that the arts and crafts of Punjab, Himachal and Haryana have been exhibited for the first time in the form of a gallery. In my father’s unflinching zeal for art collection lies a worthwhile lesson for art historians, collectors, critics and practitioners. The message being: contemplation of art and its appreciation is a question of conscience and not commercial expediency.

“He has brought to the fore the cultural achievements of millions of anonymous artists and craftsmen living in far off villages and secluded areas. The mindless modernisation has wiped off our cultural traditions, sounding the death-knell of even the possibility of retrieving and recording these precious heritages.”

Even though Baij Nath has added a sizeable number of vibrant items, he prefers to downplay his role in expanding the colection. “What is important is the entire collection, not who gathered it,” he says.

Considering that he has dedicated over four decades in buying some items, the passion cannot be undermined. He has bought some of the textiles from private collections in Europe and America. Each piece could be worth a fortune and he claims people tempt him to part with these, but for him they are all priceless and very close to his heart. Asked how he manages to carry forward his father’s legacy, Baij Nath says, “I often travel in India and abroad to deliver lectures, which ensures some income, which is all spent on the upkeep of the treasures.”

He mentions that in some time massive thematic exhibitions would take place in New Delhi with the collaboration of the Indian government. The first one being on Hanuman in various forms, from the collection of Aryan’s museum.

So, what special plans he has until then? Baij Nath points to the dictum on the door: ‘Think like a genius, work like a giant and live like a saint.’

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.