What should an emperor do to still the voices of those disturbed by his ruthless seizure of the throne? How to reassure the people that the Mongol hosts that lurked on the steppes had been quelled?

The answer: to play a round of golf or a game of football. Maybe a chukka of polo.

As the British Museum exhibition, “Ming: 50 years that changed China”, demonstrates, these manly distractions were pursued by the Yongle emperor (1403-1424) to enhance his legitimacy. He had indeed usurped the throne; the Mongols were a threat, so while the games ostensibly served as training exercises for the infantry and cavalry, they also proved to his people that he was in control.

Craig Clunas, professor of the History of Art at Oxford University and one of the show’s curators, explains: “By taking part — as a player and a spectator — the emperor shows there is no need to dash about getting involved in frantic crisis management. He’s on top of the situation. He can kick back. As British Prime Minister David Cameron would say: he can ‘chillax’.”

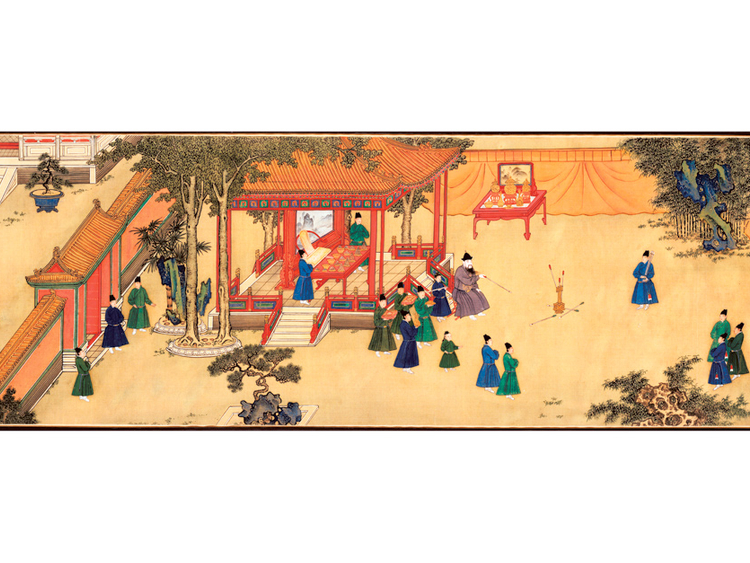

These habits and hobbies are revealed in a scroll 7 metres long, which gives us a snapshot of a society under the rule of five emperors between the years 1400 to 1450 — in which the Ming dynasty was characterised by sound government, a stable, creative, society and enhanced prosperity thanks to trade with overseas contacts. It was during this time that the capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing where the building of the Forbidden City began.

China during the Ming dynasty, which lasted from 1368 to 1644 — Ming can be translated as “brightness” — extended over more territory than its contemporaries such as the Timurids, then ruling in west and central Asia, the Ottomans or the Holy Roman Empire, let alone the French and English kingdoms or the Aztec and Inca empires of the western hemisphere.

As the catalogue lists: “It had bigger cities [and more big cities], bigger armies, bigger ships, bigger palaces, bigger bells, more literate people, more religious professionals; and it produced more books, ceramic dishes, textiles and spears than any other state on Earth at that time.”

Needless to say this required military might and considerable organisation. And the kind of good PR we see on the scroll. It was drawn in ink on silk between 1426 and 1435 during the reign of the Xuande emperor, and it is as fresh and bright as on the day it was conceived because it is only shown every five years to avoid damage by light and handling.

The detail is entrancing. Spare balls hang in nets on either side of the emperor as he watches the action, the polo players use a sling rather like dog walkers today use to hurl the ball, on the golf course a helper holds up a flag like the caddie at the green. The emperor enjoys a 14-course dinner, by himself, using one pair of chopsticks, before seven eunuchs carry him off in his sedan chair, groaning under the weight.

Ironically, many of the players were the palace eunuchs — less than manly men — captured and castrated when young and chosen to make the emperor’s meals, dress him, deliver his messages, sign his documents and serve his every whim.

Their typical subservient role is illustrated in the painting of the Xuande emperor (1426-1435) watching quails fighting, a game they still play in Afghanistan. The job of the eunuchs — readily recognised by their beardless faces — would be to coat the feathers in oil to strengthen them and then place the birds in a small sand tray where they fought over pieces of grain.

It is a task as humdrum as holding the golf flag, but with time being a eunuch became a career choice and as the exhibition shows, they rose to run key offices of state and to command armadas and armies.

As Jessica Harrison-Hall, curator of Chinese Ceramics at the British Museum, says: “They were able to exploit the fact that they were close to the emperor, they answered only to him and inevitably came to have his ear on important matters. As they became better educated, they were allowed to take over many of the court duties and became influential in the twelve agencies which were developed to handle all affairs of state.”

One of the agencies, the Directorate for Imperial Accoutrements, would have been responsible for much of the furnishings of the imperial palaces, such as the stoneware flower pots, gold ewers and basins with semi-precious stones, and cobalt blue porcelain wine vessels. The show stealer though is a jar in cloisonné style, made from metal and covered in bright enamel sections, which is fantastically decorated with rampant dragons in gold, black and red on a backdrop of swirling colours. About two feet high and wide it would have been used to brighten up the vast interiors of the Forbidden City.

Another eunuch agency published the imperial books and compiled the Yongle encyclopedia — a compilation of ancient texts on philosophy, poetry and science, while one of the most striking documents from 1447 describes the five classic human relationships which served as a template for correct behaviour — from father to son, brother to brother, husband to wife, friend to friend, ruler to subject.

It is in the world of trade and commerce that the eunuchs had the greatest impact. The eunuch Zheng He (1371-1433) worked his way through the ranks of court officials to become a bodyguard to Yongle emperor and was ultimately entrusted with the command of seven armadas — mighty fleets of up to 600 ships which kept the trade routes open and demonstrated China’s power.

The vessels were heavily armed and loaded with soldiers but they did not invade. Instead, the show of force was enough to persuade the rulers of states as far away as Java, Sri Lanka, the Arabian peninsula and south to Zanzibar, that China was a power to reckon with and to trade with — exchanging woods and spices, gold and jewels for luxury goods. (On September 16, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for the creation of a “21st-century silk road” which would roughly coincide with the ancient trade routes.)

There are no pictures of Zhen He or writings by him — though mythology says he was 9 feet tall — but there is a bronze bell, 32 inches high, which he offered to a temple in 1431 while he was waiting for the winter to pass before he could set out on what was to be his last expedition. It went missing for many years and was used as a school bell in the early 20th century before being discarded in the 1970s and re-discovered in 1981.

This “fantastic” object, as the curators enthusiastically describe it, is inscribed with Zhen He’s name and has a prayer written around the upper part which reads: “May the country prosper and the people be at peace. May the winds be regular and the rains fall in season.”

Something less obviously fantastic but the cause of just as much curatorial delight is a nondescript object which looks like a small prehistoric axe head. It is a solid gold ingot which could have been brought from Africa or India or some other trading partner on the Indian Ocean.

There is no suggestion that Zhen He brought back the ingot but other examples of trade with distant countries is there to see — an exotic gold belt set with rubies which might have come from Sri Lanka or northern Burma (rubies were not found in China) and textiles from Egypt, a graceful green-glazed stoneware bottle found in India and dishes from Borneo and Thailand.

If the appearance of Zhen He is open to exaggeration, we know exactly what another prominent eunuch, Wang Zhen, looked like. He was director of the Directorate of Ceremonial for the Zhentong emperor (1436-1449), and a modern rubbing of a stone carving made in 1443 and kept in the Temple of Attained Wisdom, the only Ming building still standing in Beijing, shows us the real man, not some genre representation. He seems to have a rather quizzical, amused look with wrinkles around his eyes and is dressed in dragon robes with his biography inscribed above his head.

In 1449 he encouraged the Zhengtong emperor to lead his troops against the Mongol armies but the expedition ended in defeat at Tumu Fort, less than 97 kilometres northwest of Beijing. Many soldiers, including Wang Zhen himself, were killed and the emperor was taken prisoner.

If the story of these 50 years is about eunuchs and emperors, it is also, says Jessica Harrison-Hall, about elite culture — as testified by the portraits of the emperors in their ponderous dignity; the obvious power of the general, Zhenwu, The Perfected Warrior; and more subtly the calligraphy, the porcelain, and the representations of Beijing and the Imperial Palace, which at the time was the world’s largest walled complex.

But the story of the exhibition is also about gods and slaves, rogues and victims. A selection of 139 paintings — drawn in about 1450 for a monastery as part of a Buddhist appeasement ritual for “hungry ghosts”, which aimed to calm the spirits of those men, women and children who died alone or with a grievance — depicts in vivid detail a world of monks and shamans and ordinary folk.

We see a woman being dragged off by attackers while her baby desperately reaches out to her for help. Her husband is stabbed in the eye while their assailants rob them of their goods, their lacquer boxes, paintings, jewellery and coins.

In another painting we meet an actor in a lion costume, a tattooed strong man, an eye doctor with an eye in his hat and an actor with a white face, black eyebrows and a false moustache.

There are relatively few representations of women in the exhibition — a reflection perhaps of their status in Ming society — but one of the “hungry ghost” paintings depicts the “Assembly of deities, saintly mother of the Earth, Empress of the Nine Heavens”. Female figures dressed like court ladies, wearing gold ornaments in their hair, float in the air like gorgeous attired spirits — their immortal status confirmed by the clouds upon which they walk.

Another, the “Assembly of forlorn souls of sold and pawned bond maids, and abandoned wives of former times” shows three young female slaves with ropes tied around their necks and bound hands, dressed in rags who are being led away by armed men, while in the background the men barter over the value of their “property”.

There are some endearing paintings of women at court; the emperor looks on benignly while the womenfolk pick his chrysanthemums and princesses play on a lacquer swing. There are dazzling examples of jewellery such as gold-encrusted hairpins, spiral bangles, and gold and turquoise earrings, but they only remind the onlooker of the low status women endured in court.

One searing account tells of women who had refused to remarry after their men had died young. They were awarded honours by the court for their adherence to strict Confucian notions of proper womanly conduct but one of them, when urged by her dying husband to marry again, replied: “What are you saying? When the husband dies all die; if you don’t believe me, let me go first,” and promptly hanged herself. This was not unusual. Sixteen of the Yongle emperor’s concubines were buried with him.

There is one woman, however, who has the last word. The exhibition ends with “Adoration of the Magi by Andrea Mantegna” (1431-1506). The Virgin Mary looks on as one of the Three Wise Men proffers a Ming blue and white porcelain bowl filled with gold. A rarity indeed in 15th-century Europe but proof perhaps that armadas like those commanded by Zhen He transported the glories of the Ming court far beyond the walls of the Forbidden City.

Richard Holledge is a writer based in London

“Ming: 50 years that changed China” will run at the British Museum until January 5, 2015