Painted in 1907, the Tate gallery’s version of Edvard Munch’s “The Sick Child” is one of the Norwegian’s most emotionally charged images. In it, a pale and feverish little girl turns towards a woman in black grasping her tiny hand. As the child rises from her pillow as if to look death in the face, her nurse or mother drops her head to her breast, bowed down in grief. All hope is lost.

As Oscar Wilde said of the death of Little Nell, it would take a heart of stone not to laugh. Painted at a time when pictures of sick children were very popular, the best that can be said of “The Sick Child” is that it shares some of the delicate sentimentality you find in Picasso’s Blue and Rose periods.

But you aren’t supposed to say that about Munch. Our response to this work has been profoundly affected by the knowledge that it was inspired by actual experience — in this case by the early death of the artist’s older sister Sophie in 1877. Talk about loading the dice. How can you look at a picture such as “The Sick Child” objectively when Munch had this to say about his art? “I was born dying. Sickness, insanity and death were the dark angels standing guard at my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life.”

Yes, yes, I know. His childhood was dreadful and his life lurid enough, but does that really mean that the act of painting was for him a way of revisiting painful memories dredged from the deepest recesses of the soul? This is the question at the heart of Tate Modern’s wonderfully revisionist “Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye”. In it, the 1907 version of “The Sick Child” hangs opposite a more freely painted replica of the same picture painted 18 years later. Both pictures duplicate the original image, which Munch painted as early as 1885. Since Sophie’s death took place eight years earlier, and since the child in the picture looks nothing like his sister by any stretch of the imagination, can any of these versions be described as an expressionist struggle to describe subjective truth or capture the immediacy of a personal tragedy?

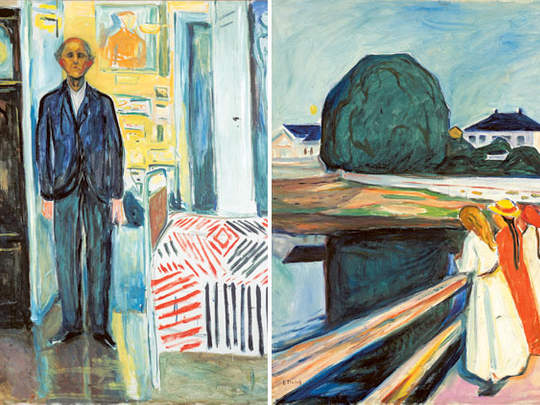

When it comes to Munch, we have become lazy. Because he often used violent colour and linear distortion, he has come to be seen as a proto –expressionist, a forerunner of Kokoschka, say, or Otto Dix. But Munch always had more to do with the controlled sensuality you find in Post-Impressionism or Symbolism than anything else, and any idea that “The Sick Child” represents a morbidly expressionist cry of anguish is dispelled by the very existence of the numerous replicas Munch was willing to paint to order or knew he could sell.

What is more, Munch’s style of painting changed with the times — or as a cynic might say, with fashion. The agitation of the brushwork in “The Sick Child” tends to increase with each version, for Munch clearly understood that the apparent urgency of the painting technique is one reason why the image tugs at the heartstrings.

To look at Munch again, this time asking whether the emotional and psychological interpretations with which his paintings are routinely burdened are fully justified, liberates his work from the stranglehold of psychodrama. As a result, he looks to me like a far greater artist — a man of his own time working in a way that his contemporaries would have recognised as modern.

Born in 1863 (the same year as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec), Munch did not die until 1944. Set aside the Nordic gloom and place him side by side with artists whose work he actually knew, and look what happens. Because “The Scream” is so famous, whenever Munch places a human figure close to the foreground of a picture or exaggerates spatial recession, there is an unexamined assumption that such expressive devices are freighted with psychological meaning. But Munch spent the winter of 1897 in Paris and returned in the two following years. He must have known the plunging perspectives in the works of contemporaries such as Gustave Caillebotte and Edgar Degas, and like them been aware of the perspectival tricks employed by the great Japanese print makers. I am not saying there isn’t disquiet in a picture such as “Red Virginia Creeper” of 1898-1900, but I am arguing that in works such as these Munch is bringing his own sensibility to pictorial devices that were fairly ubiquitous in the late 19th century.

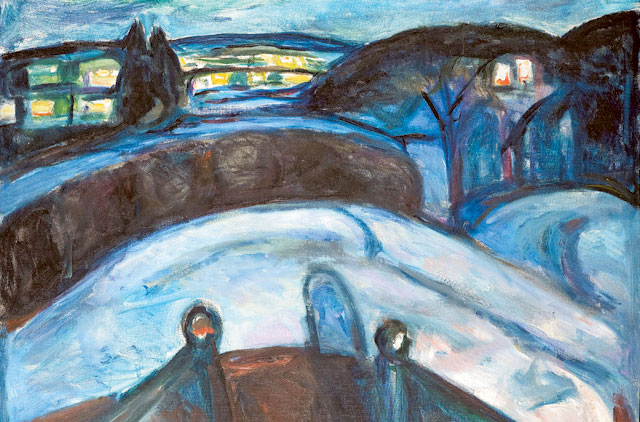

Often I think he uses these expressive devices to create visual excitement in pictures where it might otherwise have been lacking. The cartoon–like face drawn with a few swift strokes of the brush in the foreground of “Murder in the Road” and the dark smudge in the middle distance that we read as a corpse are used to animate a dull view of a road receding into the distance and leading to nowhere.

Such melodrama is one characteristic of Munch’s art that sets it apart from that of contemporaries such as Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Whether in the lurid symbolism of “Ashes” and “Vampire” or the more nuanced psychological relationship he explores in “Two Human Beings (Lonely Ones)”, a story or narrative is almost always implied in Munch’s work.

But it would be a mistake to assume that these stories necessarily have to do with the events in Munch’s life, however dramatic or damaging they may have been. Though the early death of his mother — who died when he was 4 — the religious mania of his father who raised him, the death of one sister, madness of another and his own fraught relationships with women are all well documented, so too is his close involvement with the theatre, particularly with the Berlin theatre director Max Reinhardt’s productions of Ibsen. Artists before Munch had designed stage sets and programmes for the theatre, but he is the first to be used as an artistic adviser responsible for using colour and space to establish the atmosphere in plays such as “Ghosts”. Munch’s design for Reinhardt’s 1906 production of the play featured a huge black armchair that was turned away from the stage. Unmentioned by Ibsen, the chair becomes a menacing presence on stage, a dread symbol of approaching death.

In pictures such as “Jealousy” or “The Death of the Bohemian”, we could be looking at actors on stage, where every detail — the furniture and its placement, the wallpaper, the lighting — are placed precisely to create the maximum theatrical effect. Just in case we are tempted to interpret canvases such as “Galloping Horse” (1910) as a symbol of unbridled passion, or “Workers on Their Way Home” as evidence of his sympathy with the revolutionary left, clips from silent films screened in Norway in these years convincingly suggest that Munch was simply painting what he saw at the cinema.

I am not, of course, saying that Munch didn’t suffer. He became a heavy drinker who in 1899, and again in 1908, spent long periods is sanatoriums. But Munch is no different from any other artist in the way he draws on his own experience in his art. We need to take his life story into account when we look at his work, just as we do Gauguin’s or Van Gogh’s — but also remember that he was a working artist who engaged with the world around him just as with the art of his own time. In a way it is part of that message that the works in this large show are uneven in quality and that although Munch took photographs and made films, these are of little aesthetic importance. Somehow the real man who emerges from it is ten times more interesting than the suffering loner we thought we knew.

–The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2012