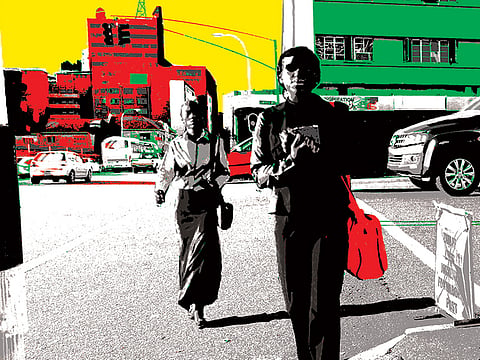

Buzzing with Zimbabwe life

From the hairdresser’s salon to the kombi bus, these short stories vividly capture ordinary lives and the tensions that call for the law

Rotten Row

By Petina Gappah, Faber & Faber, 352 pages, £13

It is the unfortunate burden of African writers that their work is often reduced to representation: as though they existed to describe and diagnose the state of their home countries, or worse, the entire continent. Yet this burden, in the hands of a brilliant writer, can be an opportunity. In “Rotten Row” Petina Gappah, who won the Guardian first book award in 2009 for her collection of stories “An Elegy for Easterly”, has produced a beautiful, sweeping collection that illuminates various aspects of contemporary Zimbabwean life. This is the country in what Gappah calls “its proper context” — that is, with character at its forefront, with humour and empathy and pathos, with the ordinary lives of everyone from hairdressers to a government executioner as its primary concern.

But “Rotten Row”’s real importance as a collection is that it does the purest work of fiction, and does it well. Gappah’s great gift is in writing the crowded scene: the interior of a kombi bus filled with the razor-sharp chatter of the driver and passengers; a hairdresser’s salon alive with gossip; a melee of relatives enjoying a punch-up at a wedding. “Rotten Row”’s vitality comes from what it tells us about people: its keen perceptiveness, humour, and above all, tenderness. Gappah has a Nabokovian delight in the inherent absurdity of human behaviour.

Even in those stories that explore more fantastical elements, such as “The Death of Wonder” (in which a police officer must deal with reports of the troublesome ghost of a boy murdered in election violence), it is the mundane moments of human weakness or folly, infused with Gappah’s wit, that shine.

Such moments can reach delicious heights, as in “Washington’s Wife Decides Enough is Enough”, where the eponymous wife defies her mother-in-law’s order not to sit in the front seat of Washington’s car on the way to a family wedding. Alongside the gathered relatives, and as eagerly excited as them by the unfolding drama, we watch as Washington’s wife sits in the passenger seat and obstinately holds a Barbara Taylor Bradford novel in front of her face, while her mother-in-law rails at her from outside the rolled-up window. The police are called, and the story ends with a tabloid headline: “Wedding party stunned by stripper Gran”.

These scenes, like the account of a kombi bus driver falling victim to the reckless justice of a mob in “Copacabana, Copacabana, Copacabana”, or the hairdressers of the Snow White Salon, with their identical Rihanna weaves, discussing the unexpected death of their colleague Kindness in “The News of Her Death”, are the bright lights of the collection.

Their excellence comes in part from Gappah’s sensitivity to dialogue; regional aspects of speech are mined for their beauty and inventiveness, fulfilling Chinua Achebe’s promise of the African writer writing in English: “Let no one be fooled by the fact that we might write in English, for we intend to do unheard of things with it.” Gappah’s facility with crowd scenes is so great that, perversely, it is to blame for the collection’s one flaw: we are not left to enjoy those moments long enough. She often arrives at the denouement of the story too early, or too explicitly leads us towards a conclusion about justice or conflict or human nature. Had we been a little more forgotten by the author — left to linger, for longer, in the back of the kombi bus or in the hairdresser’s chair — we might have reached these conclusions ourselves, left with what William Boyd calls the short story’s greatest gift, “a complexity of after-thought”: that lingering feeling after a story ends, the rumination it compels.

These sometimes premature denouements may be attributable to the collection’s stated theme, its relationship to law and justice. Gappah, a lawyer, explains in her introduction that all the stories are about “the kinds of strife, tension and conflicts that sometimes end up finding their only resolution at the courts”.

The collection is accordingly divided into two parts, “Capital” and “Criminal”, and while every story does involve a crime of some kind, the legal aspect seems less intriguing than presumably intended. The conflicts at the heart of each story are interesting and well drawn enough to stand on their own without any overt connection to law, particularly since we rarely see the court proceedings, and never in detail.

The exception, a brief moment in “A Kind of Justice”, is set in the special court for Sierra Leone. Yet even there, the searing moment in that story comes not in court, but rather when the main character, the lawyer Pepukai, is alone in bed at night, turning over in her mind a litany of the disturbing crimes the court will prosecute.

Gappah does extract engaging stylistic and narrative opportunities from the law. The collection plays with form with evident delight, and two of the most successful conceits occur in stories that mimic legal forms. “Anna, Boniface, Cecelia, Dickson” is presented like a problem question in a criminal law exam, as four people, from a security guard to a street seller of herbal cures, interact with one another in a nightmarish medley of causality and consequence. In “In the Matter Between Goto and Goto”, Gappah skilfully draws out the story beneath a judge’s statement of facts in a ruling, hinting at the muddled humanity that law’s orderliness seeks to contain.

These stories work because they exist at the most interesting intersection between law and storytelling, exploring how the elegance and exactitude of legal language belies the mayhem of human nature that it seeks to describe; how trials and hearings are really forms of cultivated narrative in which discord is made clean and presentable; how the real story — the kind that short fiction can entirely encompass — is to be found on the edges of a legal judgment, evident in legal understatement requiring us to read between the lines for the chaotic truth and squalor.

“Rotten Row” has quieter stories, too. In “The White Orphan” (a title reminiscent of Kipling’s “The White Seal”), a white British child, Jack, suffers that sudden fairytale loss of both parents, and finds himself adopted by the black half of his family in Zimbabwe. Jack, like Kipling’s white seal, feels he does not belong on account of his colour. A wise old man tells him his destiny, and he sets out on a journey to the British embassy.

The tale has a visceral, heartbreaking end, but the saddest, most tender story comes in near-biblical form, in “The Lament of Hester Muponda”, an account of a woman to whom justice and sympathy are denied. “A Short History of Zaka the Zulu”, recently published in the “New Yorker”, is the retrospective telling of the fate of a child in an elite boys’ boarding school. It is a story whose power lies in what is not said, whose loudest moments are found in its absences, and in what the reader must infer from them.

Not all the stories are equally successful, but reading them together is a heady experience. “Rotten Row” hums with life, and it delivers one of the keenest and simplest pleasures fiction has to offer: a feeling of true intimacy, of total immersion, in situations not our own, in the selves of others. In its strongest moments, we want to stay there.

Gappah has achieved the difficult task of rendering places some of her readers may never know or visit with such intimacy and aliveness that they feel instantly familiar. While this is an entrancing feature of the collection, its greatest achievements are due to her sensitivity to both human tragedy and the comedy inherent in existence. Gappah throws open the doors of a million lighted houses, and lets us look inside them. In each we find something wondrous and strange, not least a reflection of ourselves.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

F.T. Kola was a shortlistee for the 2015 Caine prize.