Framed in tragedy

An insight into the dark and convulsive story of 20th-century Hungary

Eyewitness, the Royal Academy's first foray into photography in almost a generation, is a revelation. The show presents nothing less than the dark and convulsive story of Hungary during the 20th century as experienced by its citizens and viewed by its artists, who happen to include five of the world's greatest photographers — Brassaï, Capa, Kertész, Moholy-Nagy and Munkácsi.

Nobody could fail to be struck by that fact, in room after room of famous images. That they were all Hungarians may even come as news. Each was Jewish and each changed his name at some stage, either at home or in exile. Brassaï (born Gyula Halsz), who was badly wounded fighting for Hungary in the First World War and nearly died of typhoid as a prisoner of the Romanians, left for Paris in 1924. His images of its streets and bars in rain and fog, and especially in the low glow of night, inflect our whole sense of that city.

Endre Ernö Friedmann, pioneer war photographer and co-founder of Magnum, chose the name Robert Capa to sound Italian-American in the United States. The photographs of Lászlo Moholy-Nagy (born Weisz), with their linear elegance and abstract forms, are profoundly associated with the German Bauhaus.

Martin Munkácsi (Marton Mermelstein) is the founding father of fashion photography. His 1933 shot of a tanned bather sprinting along a beach in the latest swimwear could be Lauren Hutton in the 1960s or Gisele Bündchen now. It is even titled The First Fashion Photo for Harper's Bazaar.

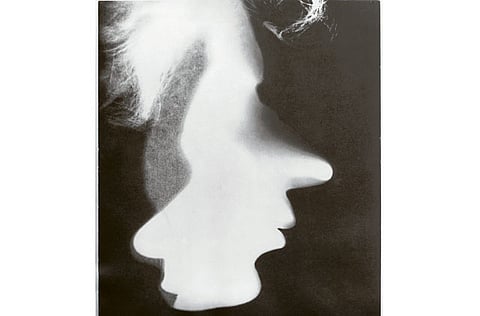

And the photographs of André Kertész, originally named Andor Kohn, are such a perfect combination of tenderness, concision and insight that he is well described as the poet of Modernism. The Royal Academy has his droll Chez Mondrian, in which the painter is fastidiously absent, represented only by the artificial tulip he kept in his hall and painted white to suppress nature's ebullient greens. Kertész's only alteration to the scene was to move the vase a fraction so that its shadow continues the trajectory of the staircase beyond. The rest is just patient framing. The masterworks are all here: Brassaï's streetwalkers, Capa's Spanish republicans, Moholy-Nagy's photograms, montages, solarisations. But here, too, is Kertész's Hungarian officer stripped of his badges at the beginning of the short-lived commune in 1919.

In Hungary, tragedy repeats itself as tragedy. There will be moments when the visitor comes upon a scene of persecution so riven with déjà vu that the eye searches for clues as to the politics of oppressor and oppressed, so often do they appear to shift.

Balogh's prints are beautiful, materialising on the paper like black-and-white watercolours. He merges two shots to get across the immense glowering sky and the smallest foreground details, each requiring different exposure times.

Eyewitness has Kroly Escher's Bank Manager at the Baths from 1938, fat and floating, stomach mountainous above the water. It has Ferenc Haar's indelible image of a labourer's bare feet. And it has Lászlo Fejes's shot of his sister and guests on the way to her wedding, which won a World Press Photo prize in 1965 but crippled his career because it showed bullet marks from the 1956 revolution on the wall of her building.

It would be hard to overstate the visual impact of the Royal Academy show. Two hundred and more images by several dozen photographers, all the way from swaying cornfields to Bauhaus architecture, and scarcely a single image that is not characterised by graphic clarity, profound empathy and a strikingly precise sense of form. Even without the five best-known names, it seems that Hungary is extraordinarily rich in its photographers.

One clue to this national gift is given in Colin Ford's essay in the catalogue. He quotes the Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler: "Hungarians are the only people in Europe without racial or linguistic relatives ... therefore they are the loneliest on this continent. This perhaps explains the peculiar intensity of their existence ... hopeless solitude feeds their creativity."