“Henri,” according to American photographer Willard Van Dike, “who was not only an intellectual but a maverick, used to go down to Wall Street so he could find a Rolls-Royce or a Cadillac to spit on.”

Yet in 1936, when the left-wing Front Populaire came to power in France, an anonymous worker-photographer took a (rather good) picture of the gates of the Cartier-Bresson textile factory at Pantin, closed by a strike. That picture was published in Regards, a magazine for which the young Henri Cartier-Bresson also worked sometimes. The embarrassment of being so obviously branded an heir to one of France’s larger industrial fortunes made the young communist activist sign himself plain Henri Cartier for many months to come.

Such is the careful scholarship deployed by Clément Chéroux, the curator of photographs at the Centre Pompidou, in establishing his monumental exhibition on Cartier-Bresson. His aim in assembling a show of some 500 artefacts (including a number of paintings and drawings) is to return nuance and detail to an image of the great man that has become stereotyped over the years.

We know that Cartier-Bresson invented the expression “the decisive moment”, which so neatly wraps up the laden immediacy of photography; we know he founded the Magnum agency. For most of us, that has been enough: quick reflexes and a vague impression of a social conscience. A photographer.

That is how he wanted it. From early on, Cartier-Bresson would have it that what he did, photography did. Like his near-contemporary, Jacques Henri Lartigue, a prosperous child connected to an industrial fortune, Cartier-Bresson dallied with an artistic career before forging a new path as a photographer from about 1930; shows in the United States and Mexico quickly followed. After the Second World War, in which Cartier-Bresson spent almost three years as a prisoner of war, came a triumphant 1947 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

But the troubled times of the 1930s had a deep effect. We forget that in 1934 there were right-wing riots in Paris, and serious fears that France might succumb to fascism. Cartier-Bresson was formed by the Popular Front too. Chéroux makes more of Cartier-Bresson’s communist sympathies than some previous scholars have. Where Lartigue chose to stay in the gilded zone where he was brought up, Cartier-Bresson chose the streets, and preferably the streets in which change was happening. In the early 1930s, in both Mexico and the US, he frequented overtly communist groups, and when he came back he worked for communist newspapers.

Cartier-Bresson had been a surrealist too, a pupil of the painter André Lhote, and Chéroux focuses on the tight formal strictures involved. He reproduces in the catalogue an eye-opening analysis from 1951 by the photographer Maurice Tabard, in which one of Cartier-Bresson’s famous pictures through a pierced wall in Seville in 1933 is shown almost in every detail to correspond to the golden mean.

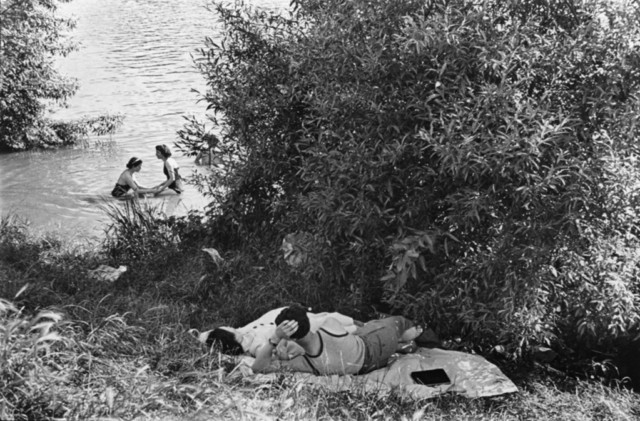

Cartier-Bresson’s method was often to position himself against a scene that had the right kind of interest, and then to wait until someone populated it. At its best, this method produced masterpieces: the bicycle whizzing past the foot of the stairs in “Hyères” (1932); the syncopated dance of the black-clad figures framed in iron railings in “Scanno” (1951). The formal perfection of Cartier-Bresson at his best is frequently seen again here. But it is not the only point of the exhibition.

To give a fully rounded picture, the curator has had to debunk a few myths. That is not so easy to do with a figure of the monolithic solidity of Cartier-Bresson. For many, Cartier-Bresson was photography, not only its presiding genius, but also its apologist and defender. It suited him to promulgate a few strong lines. He never used flash. He never cropped a frame. He never retouched. He stuck to the same trusty 50mm lens.

The myth of the pure photographer, in other words. Chéroux, curating with a light touch, has taken some of this apart. He has found evidence that Cartier-Bresson did own a flash, that he did carry a number of lenses, and so on. The simplified outline that Cartier-Bresson presented to the world was not false but nor did it tell the whole truth.

There emerges a thoroughly engaging version of Cartier-Bresson, an intellectual with a camera, reacting acutely to the world around him. By showing mainly vintage prints, in all their variety of size and chemistry, with all the range of densities of black, Chéroux gets us away from the rather routine exhibition-print sameness associated with Cartier-Bresson. Indeed, one revelation here is how much less exciting his pictures were after about 1950, once he had established himself as the grand roving reporter.

There are a number of highlights even in a show of such consistent interest. One is a study of a sweater drying on a line, no title, dated only c1931. The lightly kinked washing line looks like a taut pencil line, wobbling just a bit under tension. It is lovely. But for some reason Cartier-Bresson (remember, the myth is adamant that he never retouched) took against the clothes pegs and scraped them clumsily off. The point is unmissable: those little scratchings are the moment when Cartier-Bresson stopped being a photo-reporter and became an artist. He broke his own rules because he had to break them.

Oddly, a number of the great images in this huge show are drapery studies. Nothing “decisive moment” about those: just classic meditations. They are also, in their rumpled, lived-in way, as near as the rather prissy Cartier-Bresson ever got to the personal. Chéroux has been able to insert into this very full picture even a delicate hint of the photographer’s life. We meet his first wife, Ratna Mohini, a lissom Javanese dancer. We see a holiday in which he seems to have shared the attentions of Leonor Fini with his friend, the writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues. On a trip to Cuba, he seems to have noticed the women more than usual. Nothing coarse; just a touch of life.

In 1937, Cartier-Bresson made a series of pictures for the communist evening paper Ce Soir. Called “The Mystery of the Lost Child”, each is a study of a kid, outdoors, well wrapped up, usually photographed from the waist up. Great studies, as you’d expect. It was a promotion for the paper. If this is your kid, turn up and we’ll give you a prize. They weren’t really lost. It was a white lie. For a curator to show the morally impeccable Cartier-Bresson stretching a point like that is wonderfully daring. I don’t think they’ve been shown before.

There is also a little box showing a small selection of slides. It is backlit, and filled with the most magical colours. What is this? Cartier-Bresson in colour? He was so adamant that he didn’t, couldn’t do it, despised its realism ... Have a look at “Vanves” in that box. Nobody knows precisely when it was made. It shows a grey suburb with footballers, elegantly scattered, in the reddest shirts you could ever see. He may not have liked colour. But he could do that, too.

Something shifts with this show. It used to be that Cartier-Bresson was a figure of urgent relevance to working photographers. They situated their habits alongside his, for or against. There are still decisive moments, and still photographers who hunt them. But Cartier-Bresson’s time as the great yardstick of photography has passed. This massive show, so scrupulous in its rounded view, marks that passing. This is a study of a national monument but one whose great lessons have lost their urgency in the age of Instagram and of the citizen journalist with an iPhone.

–Financial Times

‘Henri Cartier-Bresson’, Centre Pompidou, Paris, until June 9, centrepompidou.fr. Then at the Fundación Mapfre, Madrid