‘The art market is nonsense’

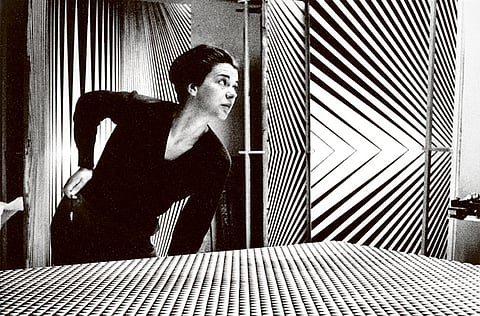

Bridget Riley, famous since the 1960s for her uncompromising lines, squares and circles, talks about abstraction, colour, freedom within strict limits and her pursuit of ‘looking’

Every one of the stucco-fronted houses in Bridget Riley’s west London terrace has a smart portico entrance with brightly painted door and shiny brass numerals — except for one, which is bare stripped wood and has the number “7” roughly stuck on with masking tape.

I ring the bell and Riley, small, energetic, 83 but looking 70, appears: tousled auburn hair, warm blue eyes, gnarled features creasing into a wide smile. “My dear girl, how kind of you to come!” she says in a tone redolent of postwar Holland Park bohemia.

She leads me through an interior where everything — walls, floorboards, stairs, banisters, fireplaces, window frames — is white. We settle in battered leather armchairs, looking into a large, high-ceilinged studio. Above us hangs a pink-orange depiction of a Tuscan plain, vast, arid, lit by a sun so fierce that it dissolves detail into throbbing dots: the only non-abstract work by this rigorous painter of lines, squares and circles that I have encountered.

“No one wanted it,” Riley laughs when I ask why she kept “Pink Landscape”. It recalls Seurat’s pointillism but dates from 1960 — in fact, it was her breakthrough. “Here I discovered the relationship between colours. My problem first of all was colour, that’s why I turned to Seurat. I found it so hard to get into colour. Difficulty is essential, something you have to probe into, find out about, unmask. You never ever stop finding out about it, ever.”

And then she shows me a canvas similarly dominated by hot, scintillating pinks and oranges, this time in regular, three-metre horizontal stripes. Just finished and leaning against a ladder, “About Yellow” was begun last year “when I found I was having a difficulty relating to yellow. Look,” she urges, “here the yellow is raised back, there it comes forward, changing the space. The yellow gives the viewer a key. If I can move this yellow — it’s a pale light colour, it’s naturally sympathetic down here, it’s at home — if it can go into the body of the red, it steps right forward. It’s a modelling of space, space made by colour.”

“About Yellow” belongs to a new large-scale series — “Red Modulation (Yellow and Orange)”, “Brioso (Orange)”, “Arioso (Blue)” — on display in “Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961-2014 at David Zwirner”.

Riley’s first major London survey in a decade, it is in effect a mini-retrospective centred on the virtuosity and surprises she achieves in the recurrent use of the stripe, changing colour, weight, density. Works range from the flashing black-and-white “Horizontal Vibrations” (1961) and the warm/cold colours rippling into pale dawn light in “Late Morning 1” (1967), to the strict diagonal diptych “Prairie” (1971), and on to the latest rhythmic, musically titled series — sonorous but still austerely ordered, brushstrokes anonymous, inexpressive.

Since the 1960s, assistants have painted Riley’s works from her preparatory notes and studies.

“Increasingly I work at a technical distance. For me the work is not physical. It has to be made, of course. Facility is important but it can also be a terrible trap. Many painters who had great facility did nothing else. So I put it aside. I give my hands to someone else. It drove me into digging into myself to find out what it was that I should do, getting a dialogue going between me and what I was doing.

Mondrian put it incredibly beautifully: ‘This is how I found this way of working.’”

As “The Stripe Paintings” demonstrate, Riley, like Mondrian, has spent a lifetime mining a very narrow field. “Mondrian came from a strict Protestant background, struggled with theosophy, which he found wanting, and he accounted for his feelings in that sphere by ordering, by his power to order what he did, to establish: red, yellow, blue, that’s going to be my discipline. That sort of ordering has an undertone of faith.”

Would she say it was the same for her? “Yes I would. ‘My freedom will be so much the greater and more meaningful the more narrowly I limit my field of action,’ Stravinsky said. ‘The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself of the chains that shackle the spirit.’”

But Mondrian’s abstraction was revenge on nature: he would change places at a table to avoid observing a tree. Riley, also a Utopian modernist, retains the luxuriance of nature. As we talk, next to the mantelpiece a panel of wavy lines, “Blithe”, ripples down like water, fizzing in the sunlight.

“I do recognise that there is a sensuality in quite a lot of my work, that’s part of what I feel,” Riley says. “I was walking past a hedge yesterday and the shine of a leaf was astonishing. It was a shiny leaf reflecting the sky, and the next leaves were matt, they were lit by light, but they did not reflect the sky.”

This sort of looking “started to happen in Cornwall”, where Riley spent the war in a primitive cottage with her mother and sister; her father “was away — we learnt that he was a prisoner but there was a long period when he was simply missing, so there was an all-enveloping climate of anxiety, the entire envelope of feeling was suspended time. The sea and cliffs and wind and little trees and flowers, what they offered, how they filled the time — the thing I discovered was the healing power of looking, in nature. My mother was an enormous influence, I not only loved her, I liked her, she would and could greet a beautiful day, see it, point it out. This would take her mind off her anxieties, and she in turn would take my mind off, into this world of looking. We were given sight. I knew that somehow I wanted to pursue this looking.”

She emerged after a “patchy” education (concluded, with a sympathetic art teacher, at Cheltenham Ladies College) to study at Goldsmiths in London; already a competent figure painter, she won her place with a copy of Van Eyck’s “Self-portrait”.

“The first thing I did was to draw a line down the middle, that’s how you start, that’s how he must have started”.

She “shared with a huge number of people the feeling that the years of austerity were over, now we could begin, we had the confidence to try”, and her dynamic early works, insistent that the illusion of movement on flat canvas is achieved by the viewer’s participation, ring with 1960s optimism for change and inclusiveness.

Unusual in the pop era, though, were her sources: convinced that “abstraction was the most significant challenge for 20th-century art; it’s grown out of the reinvention of painting”, she drew also on impressionism as a basis with which to disrupt ways of looking; she also heralded minimalism.

“I do think that the sort of beginning one makes is very important,” she says. “If one is fortunate or perspicacious enough to find a beginning which is like a piece of land that you can till, it’s worth taking the stones out and having crop rotation. Don’t get confused with a piece of bright shiny land that actually is sand, nothing will grow there.”

Thus she renounced her easy facility, “the direct depiction of people, which I had loved and enjoyed ... to find out about this new world, starting this dialogue, which I trusted, provided I could hear it and no one interrupted me, or interjected ideas of their own. What I love about this house,” she adds, “is that I can work here on my own [she has other studios in east London and France, where she works with assistants]. I get out of bed and go straight to the studio.” She has lived alone for decades, never married, has no children.

She has in her own writings quoted Proust’s painter Elstir: “It is only by renouncing it that one can recreate what one loves.” Perhaps, giving up depicting people directly, she conveys on canvas the vitality of human movement, emotion, responses to landscape, music. Or perhaps the renunciation is about art versus life. She has also mentioned how an artist — Mondrian and Proust are her examples — carries his own “text”, “his most precious possession ... source of his innermost happiness”. Does she have her own text?

“It’s pursuing this dialogue. It’s to do with a rapport, I’m tempted to say it’s to do with love, but I’m not sure. You want to show something either to a specific person or a group of people, to offer an experience that excited you, that gives you elation. The feelings you have when you love something: you can love a sea, you think this is so beautiful, how the sea moves.”

I think the complex currents of thought and feeling in Riley’s work are marvellously focused and made accessible in “The Stripe Paintings”. For, although a celebrity ever since her inclusion in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1965 “The Responsive Eye exhibition”, Riley remains a difficult artist.

“Warhol turned up at ‘The Responsive Eye’ in dark glasses and didn’t look at anything; he was a competitive artist. But the only way anyone can enter my painting is by looking; there’s no theory in them,” she says. “The very habit-ridden public, and I’m not blaming them, want something that looks like a painting. It’s market-orientated. The art market — what a lot of nonsense. I was lucky that I managed to sell always enough to support myself, I didn’t need much.” She turns to go back to work. “But if you think you’re doing well, you only have to go into the studio — the studio will show you, my dear girl!”

–Financial Times

‘Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961-2014’, David Zwirner, London, June 13 to July 25.

Extract from Bridget Riley’s ‘The Eye’s Mind’

In the foreword to her collected writings, Riley notes that she “particularly enjoys” talking and writing about other artists as a means of making her medium more accessible. In this provocative piece from 1983, she considers the past and future of abstract art.

[The 20th] century has been one of dramatic changes within the visual arts, and there is no reason to suppose that the pace will slacken. However, looking back on the past eight decades, the sources of change seem themselves to have shifted. In the earlier years they seemed to spring from a genuine desire within the artistic community for renewal. Latterly fashion has come to be a significant source of motivation.

I think it very probable that in the future there may be a divergence of paths: one tendency will come more and more to resemble the world of pop music, with group following group or movement following movement, supported by a vast promotional structure. Simultaneously, genuine development will tend to go underground. Thus the western world will produce an inversion of the effect of totalitarianism, with commercialism replacing party ideology as the dominant factor. Consequently, for each succeeding generation the task of disentangling the worthwhile from the ephemeral among recent as well as current painting will be increasingly difficult.

In my view the innovations of the second half of the 19th century and of the first half of our own [the 20th] have not yet been fully developed and still carry the seeds for the future. Alas, since the Second World War, this precious heritage has been plundered in such a damaging and superficial way that both artists and the interested public feel disillusioned and sense that modern art as a whole has somehow let them down or simply failed. Yet one has only to go back to the works of the great innovators to see their true stature and to regain access to the still imperfectly appreciated wealth which they bequeathed.

Great periods of artistic flowering are rare and short: only 30 years for the high point of classical Greek art, for instance. Valid insights, however, hold good, even if they are neglected during periods of decline and doldrum. Abstract painting, now some 75 years old, is still relatively in its infancy. If Mondrian was the Giotto of abstract painting, the High Renaissance is still to come.

In particular, the potential of what is called abstract colour painting, which places particular emphasis on the interplay between colours, has barely been touched. I would expect and hope that by the year 2020 abstract painters will be extracting from this endlessly rich seam a range of exciting work that will genuinely enlarge the vocabulary of art and our perception of the world around us.

From ‘The Eye’s Mind: Bridget Riley Collected Writings 1965-2009’, edited by Robert Kudielka, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox