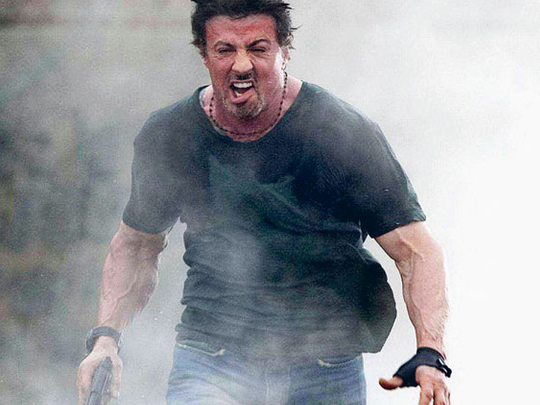

I worked a lot on my forearms because I knew there was going to be a lot of gripping, a lot of wrestling, a lot of holding." Sylvester Stallone holds up a pair of beefy fists to demonstrate the fine art of action-hero gripping. "I wasn't planning on taking my shirt off, so I decided to work on the lower part of the arms. Then I worked on my legs because I knew I was going to be doing a lot of running."

The star of six Rocky films and four Rambo films is giving me a guided tour of his physique to demonstrate how he got in shape for the making of his new action film, The Expendables. It is an impressively dispassionate tour. No bragging or vanity. Just an old pro explaining the workings of a splendid piece of machinery, albeit vintage machinery that is no longer quite so reliable. "They say, you should try and approach every film as if it's your last film. At my age, it's a reality." At 64, Stallone has mortality on his mind.

We meet in a suite at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills. The lights are dimmed and some pale linen curtains are being blown by a breeze. It is like a seance for Norma Desmond. Out of the gloom steps Sly, looking coiffed, crisp and tanned.

Ageing in style

He wears a fine beige suit, white linen shirt and mirror shades. On his wrist is an outsized chunk of silver wristwatch. It is, I learn later, a 60mm Panerai Egiziano, the largest model they have. Stallone fell in love with the watch's "star power" when travelling in Europe. He bought up a bunch and gave them to his action-hero friends such as Arnold Schwarzenegger. "Also, the large numerals are easier to read at my age." This sums up late-period Stallone: the unabashed use of celebrity wattage undercut with enough self-deprecating humour to keep him approachable.

Of the three big Eighties action heroes, the Planet Hollywood troika — Stallone was the relatable everyman, the otherwise absurd mass of muscle who was most like us. Schwarzenegger was the machine. Bruce Willis was the quipping idol.

Stallone was, dare one say it, the tragedian, the tortured underdog of macho melodrama. The story of Stallone's big break is as oft-told as Rocky itself and according to the studio PR department, no less fanciful. As the legend goes, Stallone got United Artists interested in his script about a washed-up boxer who gets a title shot but insisted he play the title role.

The studio kept offering him more money, intending to cast a big star but even when faced with an offer of $18,000, the broke unknown refused to budge. But Gabe Sumner, who was then head of marketing at United Artists, had concocted the whole thing for Stallone to ply to the press. "It worked. It promoted the whole underdog concept and kept on going," he said in 2006.

The truth, apparently, is even more bizarre. According to Rocky producer Robert Chartoff, Stallone was always approved by the producers for the role because the budget was so small; they had even helped him rewrite his script. And the studio had no problem approving Stallone after watching a screening of his 1974 film, The Lords of the Flatbush but only because they mistakenly assumed he was the lead, played by blond-haired, blue-eyed Perry King.

The film was a word-of-mouth sensation, a Cinderella success story off-screen and on, topping that year's box office and winning three Oscars.

Desperate not to be typecast as the inarticulate bum, Stallone went to great lengths to cultivate an image of intellectual action hero. He collected paintings, enthused about arcane artists, discussed Edgar Allen Poe in interviews. He posed as Rodin's Thinker for Annie Leibovitz. But it was a high-wire act that was increasingly toppled by his films; the grit of Rocky and First Blood gave way to a string of bloated mirthless cartoon violence in the late Eighties: Cobra, Lock Up, Over the Top, Judge Dredd.

Looking back, he is very clear-eyed about where he went wrong. "A lot of guys have muscles. I think it's important to show that even under all this strength, there is a fragile side. You've got to show your soul. Otherwise, you're just a piece of equipment."

He wrote the first draft of Rocky in a three-day frenzy after being so broke he had to sell his dog. When filming First Blood, Stallone is alleged to have violently clashed with the director, Ted Kotcheff, at one point breaking three of his ribs. And he objected so vehemently to the original ending where Rambo committed suicide, he was sued by the studio to ensure he would return to the set and film it.

"After the first screening in Las Vegas, I went out into the alley and threw up. It was all wrong. Artistically totally correct. Emotionally totally wrong." The ending was reshot with Rambo getting to live. "That's the difference. It's not naturalism. It's dramatic realism. The films are realistic fantasies. Bullets are easy. You can buy them. Emotions are not. They're priceless." So would he want to do another Rambo? "No. There's nothing left to kill!"

Popular character

While filming The Expendables on location in Brazil, Stallone would get mobbed even in the most remote village. "It's mind-boggling because I know it's not me. The image of Rocky or Rambo. Of course, it took me 30 years to find that out." He laughs his trademark lopsided yuk, yuk, yuk.

He says the adulation is different now. "It's more genuine. It was more of a sensual screaming rock-concert feel in the mid-Eighties. Because you're not hot any more. You can only be hot once, that's when you get discovered, that's your moment. This is the second or third generation, who've grown up watching the films on TV."

The Expendables, which he also co-wrote and directed, is an unabashed retro affair that brings his action career full circle. It is his farewell to "hellacious mayhem", an ultra-violent men-on-a-mission romp with an all-star cast of ageing baddies such as Mickey Rourke and Dolph Lundgren. It even features cameos from Willis and Schwarzenegger. "It's my homage to films such as The Professionals and The Wild Geese. It's a tried and true formula about male camaraderie: men behaving badly but in the end doing something worthwhile."

For midlife males (such as me), who grew up on Eighties action heroes, it is not just a return to form, it is a place called home. "Yeah," Stallone agrees.

Stallone's mercenary supergroup get to ride motorbikes, smoke stogies, strafe a waterfront from an old seaplane, depose a South American dictator and swap quips during hand-to-hand combat.

This isn't old school. This is the school they knocked down to make way for the old school. He says it is not self-consciously filmed in an old-school style. "It's just how I direct. You direct according to your generation. Clint Eastwood directs in a style he learnt in the Seventies. A guy like [A-Team director] Joe Carnahan, he directs like the Nineties, 2000. I wish I was that versatile. This is my Seventies style."

The key shift for Stallone was realising he no longer had to chase new younger fans; he could grow old gracefully with his original fans. "You have to be really loyal to the people that supported you when you were coming up. When you try to reach out and dress a certain way, like ‘Yeah, I'm hip', it's pathetic. Like I'm starring in the remake of Tron. I don't think so."

He is, nonetheless, uncannily well preserved for a man his age. He looks suspiciously taut, but not puffy as when he was fined by an Australian court in 2007 for importing 48 vials of Jintropin, a restricted human growth hormone product. "I got in shape for this film because I knew it would be destructive. I got hurt on Rambo IV, but I didn't have one physical altercation. I just shot people. Halfway though this film, I could barely get out of bed. There are these things called gravity, brick floors. It was like Valley Forge."

He lights up when I propose we tally up the injuries he incurred during filming. I have even drawn a body diagram for us to annotate.

"Hmm. Let me see," he muses like a connoisseur. "I injured both shoulders. I had a ruptured rotator cuff that had to be surgically attached. I got shingles on the neck. I got thrush. Bronchitis. I had both knees drained. I fractured my spine. Steve Austin [the wrestler] threw me against a wall and I got a hairline fracture in the spine. They had to insert a metal plate." So you beep when you go through airport security? "I do. I carry a pass."

Injuries to Stallone are like shoes to Imelda Marcos. "I got two stitches in the hand where I caught it on the firing pin. The doctor who patched me up repeatedly during filming, said: ‘If he was in the NFL, he'd be out for the season'."

And that's not all: "In Rocky II, I had 160 stitches under my right arm. I tore up the whole pec muscle and had to have it surgically attached. So in Rocky II, that's why he fights left-handed because I couldn't use my right.

"In Rocky IV I got a severe punch to the heart, which caused the pericardium sac around the heart to swell. I was flown from Canada to Los Angeles, to St John's hospital. I stayed there for seven days as they brought the swelling down around the heart because they were afraid it was going to swell and stop. Lloyds of London didn't believe it until they ran the footage and saw the altercation between me and Dolph Lundgren."

Stallone has decided that injuries are his lucky charm. "Whenever I don't get injured the film is a dud. I didn't bleed on Rhinestone. I didn't bleed on Stop! Or My Mom will Shoot. They hurt in other ways. Those ones hurt the soul." He gives a deep bassy chuckle — yuk, yuk, yuk.

Those two comedy flops were Stallone's belated attempt to switch gears. In the Nineties, he was out of date and out of favour. When he finally did a gritty low-key character piece, piling on 30 pounds for Copland, it was too late. Or so it seemed.

Just like his indestructible heroes, Stallone has come back swinging in the final round. In 2006, he co-wrote and directed Rocky Balboa, his coda to the series, which helped purge the awfulness of Rocky V, a film that featured a robot butler as comic relief. "The last one stank," Stallone agrees. "It was terrible. I couldn't let that be the last word on that character. He could just speak what was in his heart. When I say it, you won't believe it. But when Rocky says it you know it's the truth."

There is an awesomeness to his masculinity — the swirling gusts of aftershave, the shoulder-punching carousing. Stoicism is an essential part of his male code. In Rocky Balboa, the last of the series, Rocky tells his son: "It ain't about how hard you're hit. It's about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward; about how much you can take and keep moving forward."

Stallone's father, Frank, a retired polo player, is the glaring Freudian catalyst for his relentless capacity for punishment. According to Stallone's mother, Jacqueline, who runs her own psychic business, Frank was physically and verbally abusive when Sly was a child.

"It means I work well with chaos," is how Stallone prefers to reframe his childhood — a childhood that saw him expelled from school 12 times. "My life has always been chaotic — from the time I got dressed in the back of a deflated, flat-tyred, fish-smelling station wagon for Rocky. I am back to pretty much the way I was raised."

Stallone's family life in Beverly Hills is a carefully constructed opposite of his own fractured, testosterone-drenched upbringing. He lives with three daughters and his wife of 13 years, Jennifer Flavin. "Everything in the house is female. The toys, the housekeeper, all the dogs. The one dog I have that's male is neutered. I am next," he says, "I have my man cave, the garage, which is covered in crap and I love it."

He says the secret of peace of mind in a marriage is pre-emptive surrender. "It took me 19 years to realise she's always right. I realised that women have a knack, at least Jennifer, for making erudite, wise, smart decisions. I always leap without looking. She always looks and never leaps. She is incredibly safe. So now finally, I say: ‘Honey, you make all the decisions. Done, done, done. I trust you.' I never had that before. Ever."

Things weren't always so sane. In the Eighties, Stallone had a tumultuous marriage to Danish actress Brigitte Nielsen.

"I've concluded that love is a temporary form of insanity and we should cut each other some slack," he says.

We sit in the gloom with the billowing white curtains. "I consider my life 10 per cent on target, and 90 per cent mistakes." Stallone places his beefy hands in his lap. "But those 10 per cent counted."