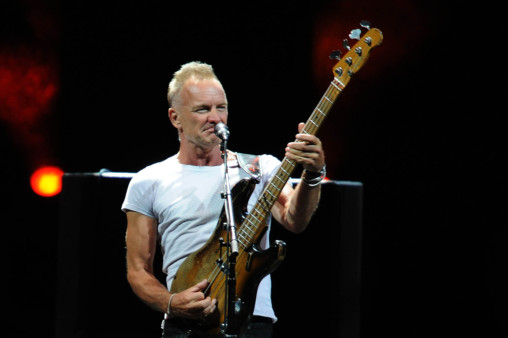

Sting’s ill-fated musical, The Last Ship, which closed on January 24, may not have ignited Broadway, but the show had some personal payoffs for the 63-year-old singer-songwriter who performs a sold-out show in Dubai at the Jazz Festival on February 27.

The $15 million (Dh55 million) show, a musical allegory set in Newcastle, the hardscrabble, post-industrial English seaside city of his youth, featuring a 29-member cast as little known as Sting is world famous, marked his first try at composing a musical, one that has taken on the proportions of an intensely emotional, deeply personal mission.

For one, writing the piece irrigated a creative desert for him, the longest dry songwriting spell of his career.

“What preceded the writing of this musical was an eight-year period of not writing songs. A fallow period,” says, still in possession of the sleek build of a rock sensation half his age, in an interview in New York before the show closed.

“I had them before but never to this extent, which began to worry me. I mean, songwriting is a kind of therapy anyway: You’re digging stuff up. I felt I needed some therapy. Regression therapy is what I landed on, going back to my childhood, which was not particularly happy, dredging up stuff that perhaps I would have kept suppressed if I’d had my druthers.

“But there wasn’t any choice. There was a compulsion to tell this story and once I decided to do it... it was as if the songs had been kind of stuck there for a long time, almost fully formed.”

After a lunch meeting with lead producer, Rent veteran Jeffrey Seller, Sting says, “I went back to my apartment on Central Park West, sat down with a notepad and wrote the names of the people I knew, people I went to school with.”

Verses poured out of him, and the basics of the show were laid out, “all in one afternoon. Reams and reams.”

Since the mixed reviews that arrived after its October 26, 2014, opening night, The Last Ship, with its 20 Sting songs, lost about $75,000 a week. Such a statistic is usually the death rattle for a Broadway production. To Sting, though, it was a call to action. Putting his star power further on the line, he took over the role earlier filled by his friend Jimmy Nail. Still, he departed in late January, committed to a concert tour of Australia and Europe with his friend Paul Simon, and the show closed on January 24.

“I enjoy having hits,” he says over the phone a couple of days after his starring gambit was announced. “I’d rather have a hit against the odds than a hit that obeys the formulaic rules. This is exactly the play I wanted to put on. It may be difficult, it may be ugly, but it’s the one I wanted to do.”

You do have to wonder why, at this comparatively advanced stage of his career, he needs what some might regard as the aggravation of a musical on Broadway, a complexly collaborative form in which so much is out of a musician’s control.

He will allude to his battle readiness again and again, although his genteel tone is absent the menace he projected as the sexually dangerous, platinum-haired frontman for The Police. The post-punk rock trio he created with Stewart Copeland catapulted him to wealth and fame in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, with hits like Roxanne and Every Breath You Take. He’s a father six times over and a granddad several times, too — “Grandpa Sting”? — with enough money and causes (notably, his Rainforest Foundation) to occupy a whole hive of Stings. He’s even got a CBE from the queen, for goodness sake — the precursor to knighthood. Plus he still gets a big kick out of the vagabond life of a rock star: “I enjoy the hurly-burly of it, the peripatetic nature of it,” says this onetime schoolteacher with the impressively posh vocabulary.

Though he sometimes strikes fans as aloof, his longtime aides say that no one is more loyal, or dependable. But this is also a labour occasioned by a lifelong sense of unfinished business.

Emotional impact

Inspired by his early memories — not the least of which are of Rodgers and Hammerstein albums as the background music of his childhood — the show and its evocations of wayward sons and tense households are linkages to a past he’s still grappling with. “I couldn’t have prophesied the emotional impact of this play both on myself and on audiences,” he says. “I think much more than perhaps I intended.”

Raised just outside Newcastle in Wallsend, a rough-hewn English town with ruins dating back to the Roman empire, Sting — Gordon Sumner — grew up the oldest of four children of Ernie Sumner, a stoic milkman, and his more vivacious but restless wife, Audrey. His ancestors worked in the shipyards, which loomed in his early life as places that were “toxic, dangerous, noisy, frightening.”

He said as much in Broken Music, his keenly observed 2003 coming-of-age memoir that presages the themes of his musical. “The ships leaving the river,” he wrote, “would in hindsight become a metaphor for my own meandering life, once out in the world never to return.”

It was the success of the Beatles, whose stories of working-class upbringings in Liverpool resembled his own; the gift at age 11 of an uncle’s hand-me-down guitar; and a copy of First Steps in Guitar Playing, by Jeffrey Sisley, that set him on a tuneful path. “This book will teach me how to tune the heirloom guitar and introduce me to the rudiments of strumming chords and reading music. I’m in heaven,” Sting recalled in his book. (He was given his famous nickname at age 21 by Gordon Solomon, leader of a group he was playing with at the time, the Phoenix Jazzmen, who decided a black and yellow sweater that Sting wore reminded him of a bee.)

“I had a dream about being a successful musician,” Sting says now. “Where that confidence came from, I do not know. But I had it for a long time. If you dream something hard enough, it will tend to happen. I think I got lucky. And then you have to get smart real quick.”

Sting was a tax clerk, a teacher or simply on the dole in the years he spent as a struggling singer and bass player, in bands doing gigs for pittances in the towns in the English north. In 1976, he took a chance, moving with his then wife, budding actress Frances Tomelty, and their baby, Joe, to London. (He’s been married to second wife Trudie Styler for 22 years.) Copeland, an American drummer living in London, had heard him play once, Sting recounts in the book, and told him to drop by if he ever was in the city. That contact would set in motion the creation in 1977 of The Police, with guitarist Andy Summers joining them soon after.

With Sting writing their songs, The Police became a global phenomenon, touring the world, winning awards and producing five studio albums and a slew of hits, among them Message in a Bottle and Don’t Stand So Close to Me. They were also growing apart, with Sting establishing a presence as an actor in movies such as Quadrophenia (1979) and Plenty (1985). By the mid-1980s, they had split, a dissolution so unpleasant that Rolling Stone magazine took note of it in an article last year titled “The 10 Messiest Band Breakups.”

On the way up, however, Sting had found his lyrical voice. The Police had charted a course, under the influences of musical sources as varied as rock ‘n’ roll and reggae, and guided, too, by Sting’s instincts for dark romance. One song that became a signature was inspired by a poster Sting saw one night in his Paris hotel, for a production of Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac. He’d come across it after walking by some ladies of the evening, and somehow the name of a character from the work became fixed in his mind and set his imagination alight.

“I will conjure her unpaid from the street below the hotel and cloak her in the romance and the sadness of Rostand’s play,” he wrote, “and her creation will change my life.”

The name, of course, was Roxanne.

“I like to create earworms,” Sting is declaring. “I like people sending me emails saying, ‘You bastard, I can’t get that [expletive] tune out of my head.’ Something’s working? Play it again!”