Clad in a red-and-silver outfit that looks part Iron Man, part Michael Jackson, Leehom Wang soars via high wires over a sea of frenzied fans and onto the stage of Beijing’s iconic Bird’s Nest stadium.

For the next two and a half hours, he rocks out on a dragon-shaped guitar, tickles the keys of a white piano, powers through hip-hop dance numbers, picks up his violin and even does a solo on the erhu, a traditional stringed Chinese instrument.

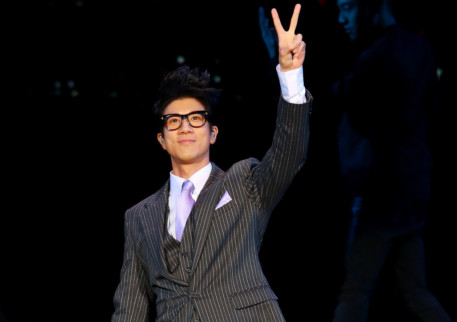

Women in the crowd swoon and sing along with Wang in Mandarin, a language the suave, 38-year-old native of Rochester, New York, didn’t really begin to speak until studying it at Williams College in the mid-1990s.

Wang might be the biggest American star America has never heard of.

He’s put out more than 20 albums and shared a stage with artists as diverse as Kenny G and Usher. During his last tour, spanning two and a half year and 56 cities, he’s performed for more than two million fans. On the final stop, in mid-June at the Bird’s Nest, few in the packed house seemed to know — or care — that Justin Timberlake had backed out as a special guest at the last minute.

“People always ask me, who’s that guy you play with in Asia and how big is he?” says Brendan Buckley, an LA-based drummer who has toured with Wang for the last several years. “I tell them, ‘Well, I fly over once a week to China and I play a soccer stadium.’ That’s how big he is — and he’s also an actor, a screenplay writer, a producer and he plays every instrument.”

Wang’s LA debut at the Bowl, however, hints at more stateside exposure to come. With a Hollywood movie, a 3-D concert film and a new album on the horizon, a tantalising question seems to be hanging in front of him: Could this son of the Empire State leverage his Chinese fame into a rare career that truly transcends Orient and Occident?

“Absolutely,” says director Michael Mann, who cast Wang alongside Thor star Chris Hemsworth in his cyber-thriller project due for release in 2015. “He’s in a perfect position to do it.”

Mann admits he had no idea of Wang’s star wattage until he was filming with him last year on Hong Kong’s Nathan Road and ran into an unusual problem: Wang has endorsed products including Nikon cameras and Coca-Cola, and his face was splashed across a giant billboard nearby.

“I couldn’t point the camera one direction, because there would be a two-storey-tall, half-block-wide poster of Leehom,” Mann says.

Ang Lee, who cast Wang in the supporting role of a patriotic young drama troupe leader in his 2007 Mandarin-language, 1940s wartime drama Lust, Caution, had a similar experience filming in Shanghai. Crowds of young girls would gather nearby, Lee says. “If they didn’t see him, there would be group hysteria, crying — I’ve never seen that before.”

Such celebrity is a far cry from Wang’s middle-class childhood as the son of Taiwanese immigrants in upstate New York. His father’s medical residency brought the family to Rochester. Wang studied violin and other instruments as a youth and performed in musicals in junior high.

“That’s where I learned to sing, dance and act,” Wang says in an interview from LA, where he’s spent the last several weeks collaborating with the DJ Avicii, among other projects.

The first album Wang bought as an adolescent was the Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill; his first concert was Heart, at the War Memorial in Rochester. As for Chinese pop music, though, Wang says he recalls hearing it only once as a youngster — when his singer uncle, Li Jian-fu, paid a visit in the 1980s and played his nationalistic-patriotic hit Descendants of the Dragon in Wang’s living room.

Torchbearer for 2008 Olympics

Wang didn’t know it then, but he would go on to remix Descendants of the Dragon for a new generation, adding new lyrics about his parents’ own immigrant experience. Over the last decade, Wang’s songs have frequently emphasised his dedication to and pride in his Chinese heritage — themes that reflect his personal journey and have a powerful commercial appeal, particularly on the mainland.

Wang’s embrace of his Chinese roots was so strong that Beijing authorities tapped him as a torchbearer for the 2008 Olympics, and he performed at the closing ceremony.

At the same time, Wang has demonstrated a strong interest in incorporating traditional Chinese music and instruments into his hip-hop and R&B-based tunes. He dubbed the style “chinked-out,” reclaiming and empowering an American slur for Asians.

It’s a profound progression for someone who describes his childhood beyond his front door as “not very Chinese.” But after working with him on Lust, Caution, Lee believes Wang’s parents instilled a deep sense of traditional manners and values that inform his artistry today.

“I found him lovely because he’s classical. That’s his upbringing — classical music, classical tradition, being isolated in Rochester. His parents are like me, and they insist on their idealised Chinese way, their traditional way,” says Lee, who was born in Taiwan. “It’s almost like he skipped a generation or two” of negative, modern influences.

Wang may owe much of his career to a summer trip he made to Taiwan to visit relatives while he was still in high school. One day, he was with his mother at a restaurant called the Ark — which he describes as sort of a Taiwanese Applebee’s — and saw a poster promoting the chain eatery’s singing contest.

“I was so bored. I knew no one; I didn’t speak Chinese. I was there to visit my grandmother,” he says. “But I had my guitar with me, so I was like, ‘I’ll do this.’ Then I did.”

Wang didn’t make it past the semifinals, but he later signed a deal for a Mandarin record with a scout who had seen him in the talent show. “I studied classical opera, so I was always singing in Italian and German and French,” Wang explains. “I was used to not knowing what I was saying. On my first album, that was what was going on. ... My producers were kind of teaching me phonetically.”

Wang’s Mandarin got better at Williams College, where he minored in Asian studies and majored in music. After graduating, he attended Berklee College of Music in Boston for further musical instruction before heading to Taiwan.

A number of American-born Chinese, or “ABCs,” have pursued music careers in Taiwan in the last 25 years, including the band LA Boyz from Orange County and Santa Monica-born Vanness Wu. Grace Wang, an associate professor at UC Davis who has studied the phenomenon, says such “reverse migration” of Asian American artists is fuelled in part by a desire to escape US racial stereotypes of Asians that “don’t align them with being cool pop stars” — ie that they’re diligent, academic and hardworking.

Preconceptions

Unlike Latino performers or African American hip-hop or rap artists, Grace Wang adds, Asian American pop artists are often branded as imitators. “There isn’t a pop genre that they can easily claim with racial authenticity,” she says. Moving to Asia can free Asian American performers like Leehom Wang from such preconceptions.

Now that he’s made it big in the Chinese-speaking singing world, though, Wang might find it difficult to cross over back to the American music market, the UC Davis professor says.

“If he is going to cross over into the US pop market, I would imagine it would be through a film venture or something like that, like an action star,” she says. If he were to stick only with music, “he’d have to change his style. His style has been to conform to the aesthetics of the Chinese pop music industry ... which is different than the US.”

In a speech at Oxford University last year, Wang conceded that the first time he heard Chinese pop music, he thought, “This stuff is lame. I don’t like it!” But later, witnessing some fans of a Taiwanese singer, he said he concluded that it wasn’t the music that was lacking, but rather his ability to “appreciate it and to hear it in the right way.”

Now, he says, he’s deconstructed and analysed it and is prepared to be an ambassador of Chinese music and movies.

“The relationship between East and West needs to be and can be fixed via pop culture,” he argued at Oxford. With the spread of technology and increasingly democratic platforms like YouTube, he said, a borderless “world pop” culture with global appeal is nigh.

Whether he’s the one to do it, or someone gets there first, Wang says it doesn’t much matter.

“It’s just important that somebody does,” Wang says from LA. “And I think that importance informs a lot of my professional decisions nowadays — what movies I take on, what songs I sing, what artists I collaborate with. ... I think it’s so important if you’re doing anything with pop culture that you want to have influence beyond your own culture.

“I think the time is right” for material with global resonance, he adds. “The content doesn’t yet exist, but the stage is set.”