As befits her groundbreaking, decades-long career, Barbara Walters gave colleagues, cohorts and fans a full year to emotionally prepare for her retirement on Friday from The View after 17 years, and full-time TV journalism after more than 60.

Having survived Oprah Winfrey’s 2011 multiweek Farewell Spectacular, we all knew the drill. The View dutifully created The Year of Barbara, which ramped up those final two weeks to include a daily toasting, complete with lots of photos and tearful praise from her former co-hosts and a constellation of A-list celebrities. ABC named a building after her, New York’s Second Street Deli named a sandwich after her, the White House press secretary gave her a shout-out, and ABC planned to air a two-hour special devoted to her life on Friday night.

But the real Barbara Walters send-off was planned on a much higher plane.

Last week, Monica Lewinsky suddenly showed up in the news, having written about her messed-up life for the June issue of Vanity Fair magazine. Subsequent coverage (including and especially on The View) seemed legally required to mention Walters’ famous 1999 interview, which is the Single Most Watched Television Interview Ever.

Then the universe offered up the ultimate parting gift: Donald Sterling.

Not only did the scandal grant the 84-year-old Walters two big “gets” — V. Stiviano, to whom the Los Angeles Clippers owner made his original damning comments, and Sterling’s estranged wife, Shelly, — but it also provided a pitch-perfect coda to the journalist’s extraordinary career.

Crosshatched with money, sex, power and socio-political implications, the Sterling scandal embodies the modern code of personal accountability in a public forum that Walters worked so tirelessly to establish. Donald Sterling broke no laws, committed no crime; he was undone by his own words. The things he feels have become synonymous with who he is.

And feelings did not a news event make until Barbara Walters came along.

Her legacy is certainly most easily defined as that of being a pioneer — she was the first female morning show co-host, the first female co-anchor of a network nightly news show, the first female anchor to make a million dollars — but the bigger, wider wall she helped tear down was the one between hard news and feature reporting, exposing the intimate relations between power and influence, personal and political.

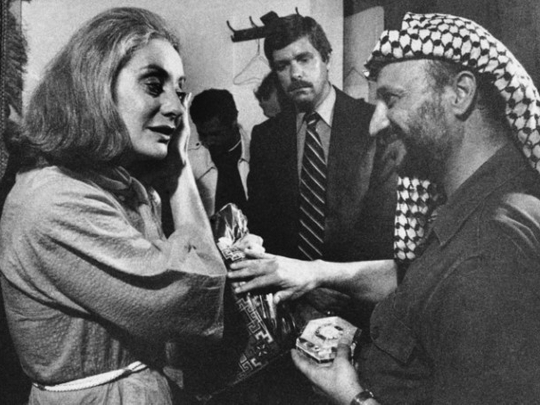

Though long lauded for her professional indefatigability, Walters was heavily criticised over the years for her brand of personality journalism. Her interviews were fashioned more as conversations, with Walters’ personality as identifiable as that of her subjects. More than that, her wide range of subjects often made her a target of derision. Walters insisted on conducting interviews with entertainers — Barbra Streisand, Michael Jackson, Anna Wintour — with the same mixture of empathetic sternness she used for heads of state.

For better and worse, the conversational interview, like the acknowledgment of the blur between power and popular culture, has become an industry standard.

When, more than 17 years ago, she announced creation of The View, it seemed to some a capitulation — news doesn’t get any softer than a morning talk show. But over the years, The View also confounded expectations and created a new template. Political and personal clashes between co-hosts (most notably Rosie O’Donnell and Elisabeth Hasselbeck) seemed to typify similar divides among Americans; during the 2008 presidential campaign, the show became a cultural touchstone and a required stop for candidates.

Politicians now regularly appear on morning talk shows, and the sight of cohosts offering their personal opinions on the headlines is all but ubiquitous.

So, as she faces down her last day on The View, Walters can be forgiven her long and self-indulgent victory lap. (Though it’s too bad the final-days festivities on Thursday could not have paused long enough for a discussion about Jill Abramson, the first female editor of the New York Times, who was fired, reportedly, for having a less than nurturing management style and for taking issue with the fact that her male predecessors allegedly made more money than she did.) Much of the criticism aimed at Walters over the years boiled down to the fact that she took herself quite seriously, which was, and remains, a revolutionary act in and of itself.

When Walters began her career, female journalists weren’t supposed to take themselves seriously enough to expect to cover big stories. When she hit midcareer, female anchors weren’t supposed to take themselves seriously enough to expect a salary on par with that of their male colleagues. As she entered her later years, female hosts weren’t supposed to take themselves seriously enough to stay in front of the camera just like their balding, sagging and wrinkling male peers.

And, most recently, many thought that an 84-year-old host days away from retirement shouldn’t take herself seriously enough to grab two big pieces of an even bigger story.

A story that, between the high emotions and revelatory TV interviews, had Walters written all over it.