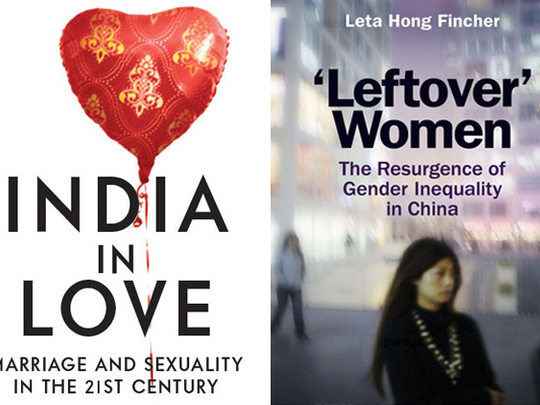

India in Love: Marriage and Sexuality in the 21st Century, by Ira Trivedi, Aleph, 424 pages, $45

Leftover Women: The Resurgence of Gender Inequality in China, by Leta Hong Fincher, Zed Books, 224 pages , $24.95

Mao Zedong said that women hold up half the sky. By the same token, between them, the women and men of just two countries, China and India, are shouldering more than one-third of the heavens. Together home to 2.6 billion of the world’s 7 billion people, both are undergoing epochal transformations that are profoundly altering the way women and men interact.

The 1949 Communist revolution in China and the more recent economic revolutions in both India and China have haltingly and unevenly improved the lot of women. Hundreds of millions of people have moved from conservative villages to anonymous cities where social mores are in what Ira Trivedi, author of “India in Love”, calls “a state of molten confusion”. That confusion ushers in the possibility of new freedoms, financial independence and forms of self-expression.

It also brings a “dark side” as old values clash with new ones, as aspirations go sour and “frustrations come alive”.

Two new books, Trivedi’s on India and Leta Hong Fincher’s “Leftover Women”, on China, describe these upheavals in important and interesting ways. Trivedi uses dozens of interviews of couples, marriage brokers, counsellors, parents, priests and prostitutes to paint a portrait of the changes, both invigorating and destabilising, that are sweeping India.

Fincher’s book, narrower in scope, argues counterintuitively that gender relations, in many ways so much more advanced in China than in India, are going backwards as traditions that were seemingly flattened by Mao re-emerge.

Trivedi, a Delhi-based novelist and journalist, writes with a fluid ease as she tussles with the contradictions of an India whose social norms are being upended by rapid urbanisation and technological change.

Like Indian roads, where cars and trucks share the same asphalt or dirt track with bullock carts and the odd dromedary, so Indian society accommodates the backwards and the modern as they jostle for space on the moral highway. Thus, a country that has “dowry deaths” (in which women are murdered over inadequate payments) and “honour killings” (perpetrated against those who marry outside their caste) is also a place of swingers’ parties and internet-facilitated casual intimacy.

As Trivedi says, this can confuse even the most liberated Indian. Some of her interviewees flirt with modern relationships before settling for tradition. Even after a decade in which the proportion of “love marriages” has soared, 70 per cent of unions are still arranged.

Trivedi traces what she calls this “schizophrenia of the Indian mind” to competing Hindu traditions. Rama and Krishna are both avatars of Vishnu, yet Rama has one wife while Krishna has 16,108. Many Hindu temples depict riotous sex scenes replete with orgies. Only in more prudish Sanskrit texts were Hinduism’s libertine antecedents suppressed.

British imperialists discouraged inter-caste unions. With more conservative interpretations of Hinduism “began a gradual decline of the social status of women: marital practices grew steadily illiberal”.

Trivedi writes about sexuality without flinching. She describes things that are bound to offend some readers. New attitudes, she says, are bringing freedoms: the possibility of divorce for abused women, or the chance to marry for love. But no revolution is pain-free. There is what she calls “a constant tug of war between past and future”.

Indian courts have decriminalised homosexuality only to criminalise it again. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court has recognised transgender people as deserving of positive discrimination. Two years ago, India was shocked by the horrifying gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old student.

Trivedi was one of those who took part in the candlelight vigils that swept India in which protesters demanded an overhaul of attitudes to rape. Yet only recently, two teenage girls in Uttar Pradesh were found hanging from a mango tree after being raped and murdered. In a distressingly familiar story, the family of the victims allege that police did not take their complaints seriously.

Alongside the violence of conservative villages is a new kind, the product of a social revolution in which millions of men with little education and fewer prospects have flocked to the liberal cities. The practice of selective abortions has badly skewed the sex ratio, increasing the frustration of young men with little chance of marrying. Men and women uprooted from their homes, writes Trivedi, “lose their social anchoring”.

Fincher, an American journalist now studying for a PhD in sociology at Tsinghua University, Beijing, also deals with the effects of sex selection, exacerbated in China by the one-child policy. By 2008, the peak, there were 121 boys born for every 100 girls. By this reckoning girls are even less valued in China than in India, where the equivalent figure is 110 boys for every 100 girls.

In both countries, feudalistic attachment to boys has resulted in “surplus men”, the so-called “bare branches” who, mainly rural, uneducated and poor, never produce an heir.

One might think women would have their pick of eligible men. Instead, argues Fincher, in China they are bombarded by state propaganda designed to make them feel inadequate. The concept of the “leftover woman”, who remains unmarried into her late twenties, plays on Chinese beliefs captured in such sayings as “men of 30 are like a flower, women at 30 are wilted and rotten”.

One purportedly pro-women organisation exhorts its readers not to be too picky by holding out for men who are rich, brilliant and hardworking. That “is just being willful”.

The idea of selfish, money-hungry Chinese women is largely manufactured, argues Fincher. The story of the dating-show contestant who said she’d rather cry in the back of a BMW than smile on the back of a bicycle is now legendary. But, as Fincher points out, such shows are heavily scripted. The author sees a coordinated campaign by a Communist party obsessed with social stability and improving the “quality” of Chinese genes.

Fincher says foreign journalists are overly impressed by China’s female billionaires and ranks of highly educated women. “The fact is, [women] are losing ground fast.” The proportion of women working in cities is falling and income disparities widening.

Some universities have taken to demanding higher test scores of women to tip the balance back in favour of men. The practice of registering property in the husband’s name has shut women out of what Fincher reckons to be the biggest accumulation of property wealth in human history. Lack of property rights also leaves women vulnerable to domestic violence.

In stressing the role of state propaganda, doubtless real, Fincher may underestimate the staying power of “tradition” all on its own. India, which has hundreds of private television channels and an uncensored internet, also has its “leftover women”. Trivedi was told by her grandfather that she should marry in her early twenties lest she become a leftover, misshapen chapatti.

Fincher herself writes that, as China dismantles the planned economy, traditional marriage rituals banned by Mao, including the giving of a dowry, have made a comeback. As Trivedi says, revolutions don’t move in straight lines. Of her attempts to cement a theory about the social earthquake rumbling underfoot, she writes: “For every truth, there was an equal and opposite untruth.”

The tug of war between past and future is not played out yet.

–Financial Times

David Pilling is the author of Bending Adversity: Japan and the Art of Survival