How China’s policy affects Asia’s great rivers

The fact that the Indus, Ganges-Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Mekong and Yangtse originate in Tibet, along with the nation’s zeal to keep the natural resources under its control, means double jeopardy

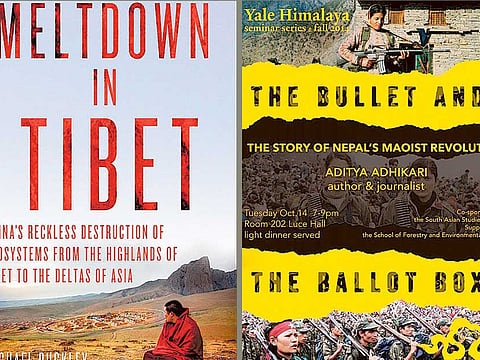

Meltdown in Tibet: China’s Reckless Destruction of Ecosystems from the Highlands of Tibet to the Deltas of Asia

By Michael Buckley, Palgrave Macmillan, 256 pages, £16.99

The Bullet and the Ballot Box: The Story of Nepal’s Maoist Revolution

By Aditya Adhikari, Verso, 326 pages, £20

Yaks have many uses. Their dung fuelled the fires of the nomads who once roamed the largely treeless Tibetan plateau. Yak milk is turned into butter, yoghurt and extremely hard dried cheese; the butter is burnt as lamp oil, used in tea or smeared on the face as a cosmetic.

Bones are carved into rosaries. Yak hair makes tents, ropes, bags, blankets and clothes, and the hides are converted into boots or even small boats to cross the region’s many rivers. The tails become souvenirs or theatre props, finding their place in opera wigs, Santa Claus beards and the costumes of Chinese lion-dancers.

Michael Buckley’s diversion into the wondrous utility of this high-altitude beast of burden is a rare moment of relief in “Meltdown in Tibet”, his otherwise relentless polemic against what he portrays as Chinese ecocide in the vast Himalayan land it invaded in 1950.

In Tibet, which makes up a quarter of modern China’s land area, Buckley says the immigrant Han Chinese have cut down half the forests, annihilated wildlife, forcibly resettled as many as 1 million nomads, and constructed dams and mines to exploit hydropower and “conflict minerals” (including “conflict lithium” for rechargeable batteries) while destroying Tibetan livelihoods and culture.

Outsiders might dismiss these disasters (if they ever learn of them) as significant only for the 6 million or so Tibetans in China. But Buckley has more: Tibet’s 37,000 glaciers, its ecological status as the “third pole” — the largest store of ice after the Antarctic and the Arctic — and the great Asian rivers that rise there mean that nearly 2 billion people rely on Tibet for their water. The rivers feeding five “megadeltas” — the Indus in Pakistan, the Ganges-Brahmaputra in India and Bangladesh, the Irrawaddy in Myanmar, the Mekong in Southeast Asia and the Yangtse in China — all have their origins in Tibet.

“If Chinese engineers can master methods of diverting water on a grand scale, then the whole of Asia is under severe threat,” Buckley writes after analysing one of Beijing’s engineering schemes to send huge quantities of water eastward into China from the rivers of the Tibetan plateau.

Buckley, who wrote the first modern guidebook to Tibet in 1986, will be accused by the Chinese of alarmism and of opposing all forms of economic development. His criticisms of such projects as the road tunnel linking Lhasa to its airport certainly seem perverse, and there is unnecessary melodrama in the references to “Agent Griffon”, an anonymous researcher studying Chinese hydropower schemes.

In a foreword, the Dalai Lama, the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader vilified by Beijing, is notably more conciliatory than Buckley himself, pointing out that Chinese scientists are among those who have recognised the importance of Tibet’s fragile environment.

Buckley’s book is also infuriatingly disorganised, a collection of vignettes and nuggets of research rather than a coherent analysis of the Tibetan crisis. It is, nevertheless, an important work because there is so little else on this neglected topic: China has kept out most independent researchers and journalists from Tibet for more than a decade and coerced neighbouring Nepal into cutting off the flow of Tibetans fleeing into India, where they could once tell the world what was really happening in their homeland. China, notoriously, has not signed a water-sharing agreement with any states downstream.

Given that even the environmental impact assessments for dams can be guarded as state secrets, China’s statements about Tibet should no more be believed than its assertions that it never interferes in its neighbours’ internal affairs. Only in September, Beijing sent hundreds of troops across the “Line of Actual Control” separating China from India in the Tibetan Himalayas, in a show of force to coincide with President Xi Jinping’s visit to New Delhi.

The independent nations of Nepal and Bhutan, on the southern edge of Tibet and the high Himalayas, have traditionally fallen not in China’s but in India’s sphere of influence and are connected largely to Indian rather than Chinese lines of communication. But superior Chinese roads and railways, like the country’s enthusiasm for constructing dams, have long been deployed as means of exerting influence abroad, as Aditya Adhikari reminds us in “The Bullet and the Ballot Box”, his well-researched history of Nepal’s Maoist revolution.

Young Nepalis in the 1960s were impressed by Chinese socialist propaganda and by the Chinese road-building teams in Nepal’s northeast, and the Maoists continued to build roads as a way of winning popular support during the heyday of their rebellion in the early years of this century.

China, by then, had long since moved on from Maoism to materialism, and Nepal’s Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal (known as Prachanda, “the fierce one”) never secured unqualified Chinese backing for a movement now integrated into parliamentary politics.

Adhikari does, nevertheless, provide the intriguing transcript of a telephone conversation recorded by Indian spies in 2010, allegedly between one of Prachanda’s aides and a man apparently offering money from China — to be delivered in Hong Kong — to buy members of parliament from other parties who would help instal a Maoist government.

That plan failed but the fact remains that China — secretive, expansionist and uncompromising about the natural resources under its control — remains the overwhelmingly dominant power in the Himalayan region. And, as Buckley explains, that affects not only the persecuted Tibetans inside its borders but hundreds of millions of people as far away as Karachi on the Arabian Sea and the Mekong delta in southern Vietnam.

–Financial Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox