In the autumn of 1628 a slim and rather shoddily produced book was issued by an expatriate English publisher in Frankfurt. It had 68 pages of Latin text, printed “in tiny blunt type on low-quality paper” and sprinkled with typographical errors at a rough average of four per page. Thus inauspiciously appeared one of the most influential books in the history of Western science, known by its shortened title as “De Motu Cordis” (On the Motion of the Heart). Its author was a 50-year-old Englishman, William Harvey, described on the title page as “physician to the King [Charles I] and Professor of Anatomy at the London College of Physicians”.

The culmination of years of research and debate, the book was the first to demonstrate accurately the circulation of the blood and the complex mechanics — “all the wheels and clockwork of the heart” that powered it. Its impact, says Thomas Wright in his sprightly new study of the book and the man, “was arguably as great as Darwin’s theory of evolution and Newton’s theory of gravity”.

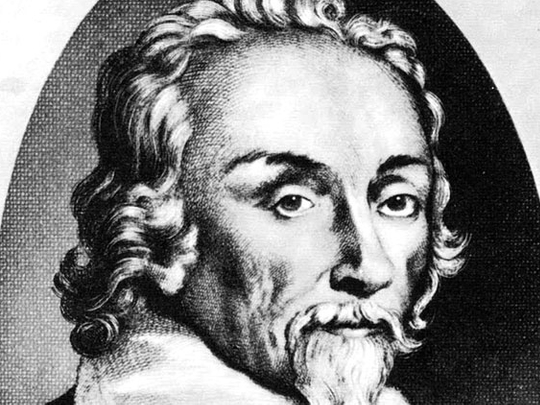

Harvey was a small, neat, busy man: “the little perpetuall mov[ement] DrHervye”. The observant John Aubrey, who met him in Oxford, recalled his “little eie, round, very black, full of spirit”, his “olivaster” complexion “like wainscott”, and his hair “black as a raven”. Aubrey characterised him as “hott-headed”, partly meaning his impatient and “cholerique” temper, but suggesting also a brain so active it was prone to overheating — “his thoughts working would keep him many times from sleeping”, and he would “rise out of bed and walk about his chamber in his shirt” (though his fondness for coffee, which Aubrey also notes, may have contributed to these white nights).

He was of Kentish yeoman stock, born in Folkestone in the spring of 1578. His father, a farmer who also ran a profitable carrier service to and from London, enthusiastically encouraged his medical studies. It is somehow characteristic of Harvey that when his father died he personally performed the autopsy, and discussed in public lectures the unusual size of his father’s colon. His own marriage, to a physician’s daughter, was childless; about the only thing he notes about his wife Elizabeth is her fondness for an “excellent and well-instructed parrot”.

From King’s School, Canterbury, Harvey went on a Parker scholarship to Cambridge (following precisely the route of another clever young Kentishman, Christopher Marlowe, a decade or so earlier). From there, in 1600, he travelled to Italy and enrolled at the University of Padua, joining a long list of 16th-century English alumni which included Thomas Wyatt, Sir Philip Sidney and Sir Francis Walsingham. There he studied under Girolamo Fabrizi da Acquaponte (or Fabricius), and watched him dissect dead criminals and living animals in the university’s famous Teatro Anatomico.

Harvey’s own pre-eminence in public dissections was much talked of. He was “unrivalled at the table”, wrote one spectator; he had “dexterity beyond compare”. Wright vividly describes his compelling performances, dressed in a white bonnet and apron to keep the blood off his clothes, brandishing a silver-tipped whalebone wand to point out the body parts, peering by the light of a candle into the excavated caverns of the corpse. An anatomy was often performed over five days, the corpse steadily decomposing as the lectures continued.

Anatomical studies had for centuries been hedged around with taboos and doctrinal disapproval: Earlier investigators, such as Leonardo da Vinci (whose marvellous anatomical drawings are now on show at the Queen’s Gallery) and the Belgian Andries van Wesel (or Vesalius), were harassed by charges of heresy. The doggedly orthodox College of Physicians still championed the classical precepts of Galen. Harvey proceeded cautiously in his contradiction of them: When his dissections pointed up the inadequacy of Galenic theories of the heart and blood, he would tactfully suggest that the human body must have changed since Roman times. For him the great guru of medical antiquity was Aristotle, with his emphasis on experiment and observation, and his study of body parts in terms of mechanical functionality.

The early scientific habit of analogy was still strong, but Harvey had no time for the then-current distillatory or alchemical model of blood circulation. His key idea lay in the more prosaic area of hydraulics. Tradition had taught that arteries had an active “pulsatory force”, but Harvey realised they were passive, like the lead pipes of London’s rapidly developing water system. Arterial blood was pumped around by the “forcings of the engine” — the heart alone. This perception of the heart as a piece of robust but intricate machinery was profoundly influential on the new generation of Neoteric or mechanistic philosophers such as Descartes, though Harvey, combative to the last, rejected their world view.

Unfortunately for modern sensibilities, the unsung heroes or victims of this story of scientific advance are the hundreds of animals who suffered vivisection (a word not coined until the 18th century) to provide Harvey with the necessary proofs. According to one early anatomist, Realdo Colombo, the dog spreadeagled under his knife was “happy” because it “affords to us a sight suitable for acquiring knowledge of the most beautiful things”. If only, mused another, “we could find a way to stupefy creatures” so that they wouldn’t have to endure this torture — but anaesthetics were some three centuries away.

Wright, whose idiosyncratic bookshelf biography of Oscar Wilde, “Oscar’s Books”, was much praised, has written a concise, skilful and often eloquent book, though it is marred by the absence of any source notes. Thus many interesting quotations are cloaked in anonymity, and many interesting statements are unsupported assertions.

– Guardian News and Media Limited

Charles Nicholl’s The Lodger: Shakespeare on Silver Street is published by Penguin.