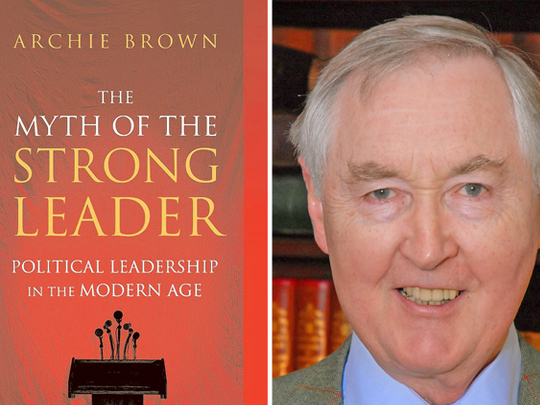

The Myth of the Strong Leader: Political Leadership in the Modern Age, by Archie brown, Basic Books, 480 pages, $21.76

Americans love to honour their former presidents: paintings, statues, libraries. Even airports get relabelled. Since 1963, travellers to New York have been touching down at JFK; Washington DC is served by Reagan national airport. There is now a campaign, led by senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri, to give Harry Truman his due by renaming DC’s main train station Truman Union station.

But the plan is facing an unexpected opponent, from beyond the grave: Truman himself. It turns out that Truman wanted a “living memorial”, rather than bricks and mortar. A scholarship programme in his name was established, helping students on their way to a career in public service. The legislation founding it, drafted in consultation with Truman’s friends and family, states: “The Harry S. Truman scholarship program as authorised by this chapter shall be the sole federal memorial to President Harry S Truman.”

This will please Archie Brown, for whom Truman is something of a hero. In contrast to self-styled “strong” leaders, seeking to achieve their aims through dominance and diktat, Truman was an instinctively collegiate president, delegating significant authority to his colleagues — especially his two secretaries of state, George Marshall and Dean Acheson.

As Brown writes: “It was characteristic of Truman’s style that the most outstanding foreign policy achievement of his presidency is known as the Marshall Plan, not the Truman Plan.”

Brown points out that Truman was brought into the presidency as a result of the death of FDR. He was “a reluctant vice-president of the United States and subsequently a reluctant president”. This is, it seems, a good thing. In his sweeping history and analysis of political leadership, Brown comes close to endorsing Plato’s view that power should only be entrusted to those who do not seek it.

Truman was modest not only about his own status, but about the powers of the presidency itself. While many US presidents — perhaps most — feel the need to exaggerate their powers, Truman said: “I sit here all day trying to persuade people to do the things they ought to do without my persuading them — That’s all the powers of the president amount to.”

Brown has provided in “The Myth of the Strong Leader” two books in one. The first, as indicated by the title, is an opinionated treatise on the idea of political leadership. The second, which takes up the bulk of the book, is a rich description of different varieties of political leadership in diverse cultures.

It is hard to imagine a better guide than Brown, who has lived and worked in the UK, US and Russia, and is both an outstanding political scholar and an elegant, witty writer.

First, the polemic. He is out to topple the idea of the “strong leader”, arguing that party leaders matter little to electoral outcomes, and wield limited individual power, except — and often fatally — in foreign policy. Clement Attlee, who became prime minister just three months after Truman became president, gets the nod of approval from Brown.

Like Truman, he was a natural delegator, and content to have powerful ministers running their departments Bevin, Bevan, Cripps, Gaitskell, Wilson. As Bevin’s biographer Alan Bullock (no Attlee acolyte) pointed out: “No politician ever made less effort to project his personality or court popularity.”

No prizes for guessing the prime ministers who earn lower marks for leadership style: Lloyd George, Neville Chamberlain, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. All suffered, according to Brown, from a suboptimal conception of the role of the head of a government: “that of the leader as boss”. And all were ejected at the hand of their own colleagues, rather than the ballot box.

But, with the exception of Chamberlain, all also make it into the top 10 of any poll ranking of great 20th-century prime ministers: the “best” leaders, in Brown’s sense, may not be the ones voters are typically electorally attracted to.

Political leaders err when they come to believe too strongly in their own powers and perception: a form of personal exceptionalism that disfigured the premierships of both Thatcher and Blair. Brown records Kenneth Clarke’s recollection of Thatcher exclaiming: “Why do I have to do everything in this government?”

He is particularly strong on identifying foreign policy as a dangerous area for overreaching political leaders. He brackets Blair/Iraq with Eden/Egypt, and painfully teases out, in Blair’s case, the path to war. There is a well-known tendency for prime ministers to tire of domestic politics, or what Max Weber described as the “slow, strong drilling through hard boards”, and turn to foreign adventures instead.

Towards the end of his time in office, Blair started to complain about the delay between “the flash and the bang” in relation to some policy reform. Ministers realised that Blair had picked up military terminology and was applying it to, say, the constitutional status of foundation hospitals. Compared with the complex, sluggish nature of public service reform, foreign policy, and especially military action, becomes seductive. You can bomb Baghdad tomorrow; improving the quality of early-years education will take longer.

Colleagues can seem an inconvenience, even if — perhaps especially if — they are foreign secretary. Contrast Robin Cook’s treatment at Blair’s hands with Denis Healey’s response to Harold Wilson’s desire to assist the Americans in Vietnam: “Absolutely not!” (Or at least, that is how Healey records it.)

In the second half of the book, Brown provides a four-fold typology of political leadership styles: redefining, transformational, revolutionary and totalitarian. For each, a comprehensive global history is provided, complete with biographical sketches of every important political leader in the last century.

On almost every page Brown offers us a historical titbit or anecdote. (I did not know, for instance, that Goebbels presented Hitler with a German translation of Thomas Carlyle’s biography of Frederick the Great.)

What he calls “redefining” leaders are those who change politics, and in particular by changing “people’s thinking on what is feasible and desirable”, he writes. They “redefine what is the political centre, rather than simply placing themselves squarely within it”.

Attlee and Thatcher were redefining leaders, Macmillan and Blair were not: “Blair accepted the new centre-ground of British politics that Thatcher and like-minded colleagues had helped to create.”

A “transformational” leader is one who changes their nation in some systematic way: Mandela in South Africa; Abraham Lincoln in the US; Gorbachev in the USSR; De Gaulle, founder of the Fifth Republic, in France. These are leaders who leave the economic or political system of their country altered.

By definition, they are rare, especially in settled polities. Brown may set the bar a bit too high here. Perhaps LBJ, who brought black Americans into the national fold and laid the foundations for US post-war welfare could be seen as having transformed his nation; ditto Attlee, for the creation of the NHS. Brown concedes that Blair may have a small claim to be transformational as a result of his semi-accidental constitutional reforms. But the only contemporary British politician with the potential to be transformational is Alex Salmond, should he succeed in breaking Scotland off from the UK.

In his desire for more humility in political leaders, Brown longs for a world in which political parties carry more weight, relative to their leaders. In his view, leaders have no role in setting the goals of the party, merely in implementing them. “If political parties become moribund,” he warns, “so will democracy.” This seems Utopian and oddly shortsighted.

Strictly defined, tightly whipped political parties have often acted against the democratic grain, rather than with it. It is not clear that democracy lives or dies with the party system.

At points, I was not sure if Brown was describing the world as it is, or as he wished it could be. It is quite likely that the UK is headed for more coalition government in the future, which requires precisely the kind of collegiate leadership Brown admires. But for such leaders to succeed electorally will require a broad shift in political and popular culture. The “strong leader” may be a myth, but it is a politically powerful one.

–Guardian News and Media