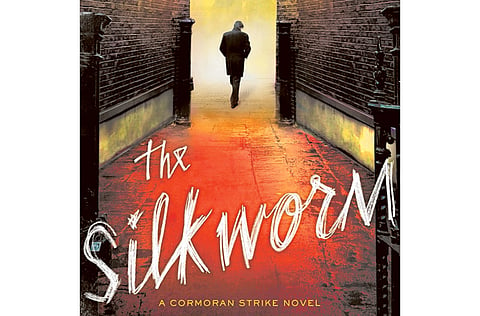

A classic whodunit

J.K. Rowling’s storytelling gift and magpie eye for genre detail make the new Cormoran Strike novel an irresistible read

When I read Robert Galbraith’s debut novel, I had no idea that the most dramatic denouement would come from the unmasking not of the murderer but of the author. Now the world knows Robert Galbraith is J.K. Rowling, and that inevitably affects the way we read these books — which is precisely what she wanted to avoid.

The delights of that first outing for private eye Cormoran Strike might have led to trepidation that Galbraith would fall into that publishing trope of the “challenging” second novel. But of course, this is actually Rowling’s 10th novel, so relieved readers are spared that particular anxiety.

However, because she has chosen to set “The Silkworm” in the world of literary publishing, she gives us the inside track on plenty of other tropes from that world. And this is no rose-tinted portrait. This is a sardonic look at a hermetic world, and Rowling/Galbraith brings flair and wit to her reflections on the state of contemporary publishing.

Here are the posh girls with the names that end in a — Nina, Emma, Sarah, Miranda — and the posh boys who inherited their role in a family firm that is now part of a conglomerate.

Here are the self-published novelists and memoirists, gulled by creative-writing courses into thinking they are only rejected by traditional publishers because they are too talented, too challenging, too individual. Here are the editors, drunk and trepidatious; the agents, greedy and bullying; and the writers, driven alternately by ego and fear. Really, it is a miracle anything half-decent ever gets published at all.

Into this seething morass comes Cormoran Strike — a one-legged, decorated ex-military policeman aptly named after a Cornish giant, the illegitimate son of a rock legend, a dogged pursuer of fraudsters and adulterers and a man whose heart sometimes gets in the way of his better judgment.

He is supposed only to be taking lucrative cases so he can pay off his debts and give a raise to his sparky PA, Robin, whose impending marriage to an accountant appears a fate worse than wrangling killers.

But Strike takes pity on Leonora Quine, the downtrodden wife of a notoriously unpleasant and unsuccessful literary novelist, Owen, when she asks him to track down her errant husband. When Strike finds Owen dead in the most grotesque of circumstances and the police focus their suspicions on Leonora, he can’t resist the crusade to prove her innocence and find the real killer.

What Galbraith does so convincingly with the crime novel is, in a sense, what Rowling did so well with the children’s book. She is a magpie, with an unerring eye for elements of the genre, both traditional and contemporary, that work well. Where her originality lies is in pulling them together into a synthesis that is entirely her own. She takes the existing strengths of the genre and uses them as the building blocks for her own considerable storytelling gift, crafting books crammed with memorable characters that make irresistible reading.

So with “The Silkworm”, there are aspects of the traditional English crime novel reaching right back to the golden age of Christie, Sayers, Allingham and Marsh. The orderly interviewing of witnesses; the closed world of the suspects; the gathering together of the cast of characters so the detective can unmask the killer. There is the Hitchcockian device of the McGuffin — in this case, the manuscript of a scurrilous novel that threatens reputations all over town.

There is the damaged detective who has trouble with women, a tradition going back to the American pulps of the 1930s. But there are also untraditional families with all sorts of configurations, as we find all around us today.

And there is the very modern exploration of idiosyncracies. The final brick in the wall is the dark confrontations the reader is forced to make with violence; Galbraith draws a direct line back to the Jacobean revenge tragedies, with chapter epigraphs that remind us a willingness to engage with the nature of extreme violence is not an invention of the 21st century.

My one reservation about “The Silkworm” is Galbraith’s descriptions of settings. There is too much detail about streets and journeys; at times it is like a travelogue of London. I suspect that having spent so many books describing a world only she knew has left her with the habit of telling us rather too much about a world most of us know well enough to imagine for ourselves.

But that is a small quibble. Certainly on this evidence, “The Cuckoo’s Calling” was a calling card for a series that has legs. With up to seven books planned for Cormoran Strike and Robin Ellacott — the same as the Potter canon — Galbraith obviously feels the same.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Val McDermid’s latest book is Northanger Abbey (Borough Press).