Oman-born and brought up and at present dividing her time between London and Muscat, artist Radhika Khimji recently held her first solo show in Oman at Barka Castle in Barka, a coastal town 45 kilometres from Muscat. The show, Safe Landings, an example of site-specific installation artworks, constituted cut-out shapes of a body in motion or "shifters" placed within Barka Castle. The additional layers of parachutes and the Castle's historical narrative and physical architecture contributed towards creating a unique art experience.

Khimji's work is not a spectacle as much as it is primarily of an experiential nature. The viewer interacts with the shifters per se and the environment in which they have been placed. "It was crucial that there was no distinction between the space of the work and the personal space [of that of the viewer]," says Khimji, referring to doing away with the metaphorical and physical velvet ropes which ultimately demarcate the viewers from that of the work.

Khimji's relationship with the shifters began in 2002, the shifters having been born as bits of paper stuck on her studio-wall before eventually migrating to being affixed on canvas. However, after having completed her Bachelor of Fine Arts at the Slade School of Fine Art, London, and beginning her postgraduate studies at Royal Academy of Art, London, she found herself being perceived as an artist from abroad and therefore, spent much time questioning what the biography of an artist had to do with the making of the work of art.

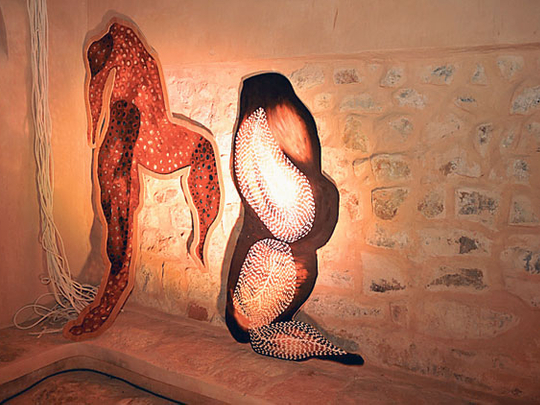

After a period of critiquing the value of culture in a work of art, the artist began making works which are stripped of context and are a description of an inner psychological space — works which largely used the medium of the shifters and which now happen to occupy a continual presence in her work. The shifters — which are essentially gestures — belong to their own realm altogether; shorn of labelling or any kind of naming, cultural or otherwise, they exist and function in a continual state of displacement, occupying the interstices between spaces.

"They are not drawings, they are not paintings and they are not sculptures. They are always on the edge of what they're not. They keep slipping out of every category," Khimji says. For her, they represent a new language that still nevertheless allows her to engage with contemporary and historical issues while remaining uncorrupted by a particular stereotyping.

The architecture of the space in which she places her shifters has always been significant to Khimji, who has exhibited in the United Kingdom, the United States, the Middle East and India, including at Saatchi Gallery, London and Bose Pacia, New York.

"The shifters are not nailed to the wall. The architecture therefore puts them up," she says. She adds that the perception of the shifters themselves alter contingent upon the space in which they are situated, therefore becoming interventions in that space. Khimji's most ambitious and large-scale work till date, she had been working on Safe Landings for the last two years. Upon reading more about the Barka Castle and port, Khimji discovered that Barka had been a strategic trade capital in the 18th century.

To prevent harassment in Omani waters, the ruling Sultan handed over the use of Muscat's port to the Persians and moved to the town of Barka. However, as the major trade routes were redirected to pass through Barka, the move enabled Omanis to regain full control of Muscat and significantly, preserve their position with dignity and strength.

Barka port and the castle represent a place and space in transition, the displacement being a powerful strategy of manoeuvre, forming a natural corollary to the shifters themselves, who reside in spaces between spaces and therefore, in a continual state of displacement. "Everybody talks about displacement and it struck me if this word could be anything else. What else was there to pull out of this loaded term?" Khimji questions.

In this particular case of displacement, Khimji chose to remember the historical manoeuvre tactic as being empowering, thus subjecting the way history is remembered to revision itself and expanding it from being a passive spectatorship of events in the yore, or clouded remembering when seen through lens of anger or nostalgia. The castle too wore another layer in addition to the many it had accumulated over the centuries: political, commercial and aesthetic before being given a fresh, contemporary context by being the site of this exciting installation. "I hope that by setting up the artwork there, the castle becomes a mélange of both the present and the past, functioning beyond being just a historic site," says Khimji, who lauds the Ministry of Tourism, Oman, for granting her both access and liberty to do whatever she wished with the castle through the medium of her work.

Furthermore, when commenting upon the physical space that the castle afforded her (although she primarily used the central multi-layered courtyard), Khimji says that there was fluidity to the labyrinth-like space, the movement within the space both ensuring and replicating a stream of consciousness thought-process. "I just found it offered so much, whether it be in sculpture, visual, or physical terms," Khimji says.

The castle space clearly played a significant role in her work although as Khimji previously mentions, the shifters themselves are such that they alter the atmosphere of whichever space that they are placed in. "For example, for the first time, [when placed in the environs of the castle] they assumed a medieval character to me," she remarks.

However, she also emphasises that the conjunction of the shifters/parachutes with the castle space does not mean that the shifters are performing a historical illustration. "After all, the shifters exist in real-time: They are fully aware, cognisant beings, existing independent of history. What I was therefore looking towards was to create an interactive relationship with the shifters and the history of the site and the structure itself, rather than collectively conflating them," Khimji says. The additional dynamics of the parachutes too contributed towards the experience, with Khimji remarking that the parachutes typified associations with arrival as well as military/fortress connotations.

The overall effect is that the shifters engender a feeling of arrival, acclimatisation of sorts to the space, whether it is the parachutes themselves or the shifters still enmeshed and part of the parachute. Yet, it is as if they are still in the process of having arrived, rather than having settled down, clinging close to the castle walls and crenellations.

Apart from the presence of the shifters, the work also included several of Khimji's mixed media collages, consisting of layers of photographs, sketches, paint and even the original plywood itself, with dense surface marks, dots, and elisions reflecting the artist's engagement with the work: A physical manifestation of the calculus of the artistic processes and thoughts being worked out. The surface-marking is an omnipresent feature in Khimji's work.

"It reminds me that I have touched every aspect of the work," she remarks, investing the works with a tactile quality while also undoubtedly evoking a mapping of the artist's presence within the work itself.

Safe Landings undoubtedly opens up radically novel vistas in terms of both accessing such vital, stimulating work and being situated in a localised historical and cultural context. It thus draws attention to the sheer contemporariness of the work whilst simultaneously forging alternate ways to engage with the past.

Priyanka Sacheti is an independent writer based in Muscat.