Harsh Mander’s recent book, “Looking Away: Inequality, Prejudice and Indifference in New India”, is bound to make the reader uncomfortable. It forces us to confront an undeniable truth of the modern India that the middle class has conveniently perfected the art of ignoring pervasive poverty and inequality, and deep-rooted bias against minorities.

It is a critique of the modern India, which continues to ignore, or even acknowledge, that it’s unprivileged. At the same time, the book is about the need to instil in our lives the values of solidarity, fraternity and liberty — the ideas framed in the Indian Constitution but ignored by the majority.

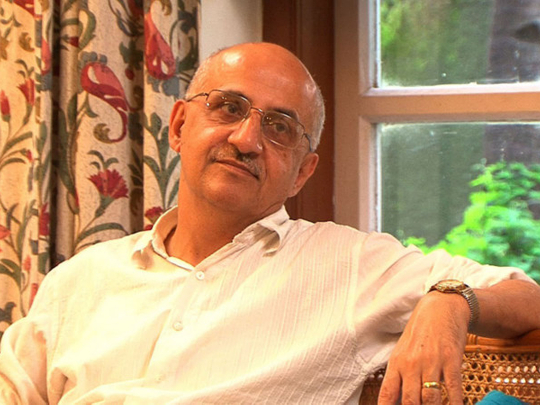

Mander, who resigned from Indian Administrative Services (IAS) after the 2002 riots in Godhra, Gujarat, is the convener of Centre of Equity Studies in New Delhi and works with the survivors of mass violence, the homeless and street children. In a freewheeling conversation with Weekend Review, Mander talks at length about what compelled him to write this book, the prejudices prevailing in present-day India, what Narendra Modi’s rise means for the country and why he believes that India can change only when the middle class changes.

Excerpts:

What compelled you to write this book?

I am deeply worried about the world as I see it. I worry about the direction in which we are moving, not just in India but in much of the world, where faith is being put in a model centred around enormous wealth generation for one segment. Not just the inequality in the society but the complete indifference of people of privilege and of the governments to what is happening to the most disadvantaged. That is one part of it.

The other part is what I call legitimisation of prejudice. It is not that there’s prejudice, but the fact that it has got legitimised in the middle-class discourse is worrisome. And that you need to worry about building ideas of social solidarity. Mainly these are the three things that me led to write this book.

Gujarat riots had a huge impact on you. What was so troubling about these riots that you decided to quit your job?

The first communal riots I had witnessed was the massacre of Sikhs in 1984. I was as a young civil servant then. I saw very closely and upfront that these are not spontaneous outbursts. The state was enabling and facilitating the massacre and the enormity of it hit me. At the same time, I learnt that if a junior [administrative] officer decides to defuse the tension, it is possible to control the situation, as we did in Indore where I was posted at the time. That experience highlighted how compound and culpable the failure is of the civil authorities to control hate-violence against minorities.

Then, during the build-up to the [demolition of] Babri mosque, I observed the same thing in small towns. I became committed to the idea of building an India where people don’t have to suffer extreme consequences of hate violence, state-driven massacres only because of the God they worship or the identity they are born with.

The Gujarat riots were the culmination of all this. I realised that such violence will threaten the idea of that India. In Gujarat specifically, the role of the state — as in the 1984 riots — was really, really obvious. After the Godhra riots, I went on a fact-finding mission [with a development organisation, Action Aid] as a serving IAS officer. I wrote a piece called “Cry, My Beloved Country!” which said that it was a state-sponsored massacre.

What made Gujarat distinct was the scale of cruelty against women and children ... I had not seen anything such as this before.

All this made me think that you can fight many battles for justice within the system, but the battle to preserve the secular fabric of the country against violence that involves the state requires one to stand away from the system.

You are extremely critical of the middle class and say that India won’t change until the middle class changes.

Firstly, as I say in my book, what we call the middle class is actually not. They are really at the top-end of the population. The country’s elite describes itself as middle class. They are the people who dominate the civil services, political parties, media, etc.

I feel that we may fight for a change in laws and policies but until the people who are responsible for implementing these laws and policies are not convinced about the legitimacy of these laws and policies, then the laws are never going to be implemented.

What I am saying is that if women are being battered, it’s not only women who should come forward to fight for them. Men should also stand with them. Likewise, when religious minorities are being targeted, it is for the majority to stand with them in solidarity. The solidarity of people of privilege [with others] is as important as organisational changes.

There have been moments in recent history in which the middle class was involved, such as in Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption movement or the rise of Arvind Kejriwal, but you don’t mention them in your book?

I think they were important moments, which did show some stirring of protest ... But these movements saw the participation of the aspiring middle class, not so much the middle class itself. Also, these movements were sporadic and single-issue based. They were unable to take comprehensive and sustained view of injustice in society and how it needs to be addressed.

I also feel that they needed to make more demands on the people battling for justice to look inwards — they have to live by the very values they were seeking, such as their own engagement with corruption.

Corruption is a huge problem but it is not a standalone issue. One might say that it affects both rich and poor. But for the poor, their very survival is at stake, whereas for the rich, it is the ability of make money that is affected.

What we need is to have a higher political understanding of what constitutes corruption, what causes it, and to locate it in the larger political economy of inequality. I am hopeful of that happening.

You were a part of the system and you are an activist now. Which is more effective?

I have worked for in the government for 17 or 18 years. In the early years of IAS, you are generally posted in remote areas and you deal with various issues, such as land reforms, communal tension, caste inequality ... I found these years wonderful.

There are many battles that you can fight within the services. But when it comes to the battle for preserving the constitutional framework itself, I felt it was important for me to stand outside the government and be an independent individual voice. For the battles that I was fighting, both spaces made sense to me.

Why do you think the Leftist movement failed to make an impact in India? The conditions are right for the Left to grow but that’s not happening.

I am greatly anguished by the decline of the political Left in India. I wish they were a stronger force. The brief experience of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) shows that there is space for different ideological positions in India. The AAP was able to win 67 out of 70 [Delhi legislative assembly] seats in such a short period and its appeal over some issues was similar to the Left’s. This shows the Left can have a greater impact than it does at present. I hope it does so in future.

Many things went wrong with the Leftist movement in India but above all, I have a feeling that it was the inability to work around caste and gender in addition to class and religious minorities. Considering religious minorities along with the working class people as disadvantaged groups ... I think that would have infused a very different kind of energy to the Leftist movement. They haven’t sufficiently made space for themselves in the unorganised workforce where 90 per cent of India’s labour is employed.

The country’s student and youth movement also needs to be more enthused to be at the forefront, for instance, in the fight against communal violence.

What motivates you to continue with the work you do?

I think just the unacceptability of what I see around me ... I should not, at any point in my life, be numbed from responding to injustice if I see it.

You are critical of Prime Minister Modi and his policies. What do you think is the significance of Bharatiya Janata Party’s win last year?

It is the triumph of a certain idea of state and of an India where the government’s primary duty is towards big corporations, and an India where one religious community is dominant and the minorities have to learn to live in subordination and fear.

I think this is a temporary setback and you are witnessing it in many countries. In the long run, we have to get back to building a just society and the ultimate triumph will be of a society where you are free to follow your beliefs, your culture and your way of life, without any fear. We have to move in that direction.

How long did it take you to write this book?

The book is like notes that were written over the last eight to 10 years. The process of putting them into a book and additional writing took about a year. I submitted the manuscript to the publisher last year, when the general elections were held. I felt that the elections represented the divide that I was writing about in a very stark and dramatic way, so I took it back. It took another six months to write the book from start to finish.

What is your biggest achievement?

I just turned 60. At this stage, one does look back on life ... I think I have tried hard to live by my beliefs and maintained a relationship with the world. I have tried never to turn away from either injustice or suffering. I may have been imperfect, but my achievement is that I have been able to live by that to some extent.

Gagandeep Kaur is an independent journalist based in New Delhi, India. You can follow her on Twitter @Gagandeepjourno