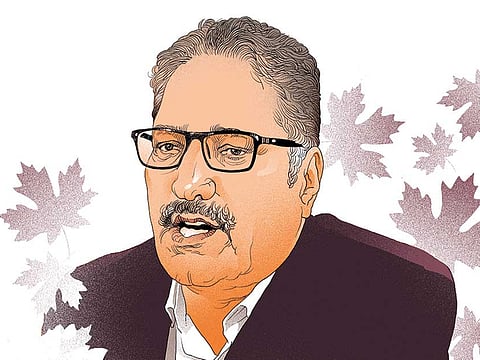

Shujaat Bukhari: An indomitable spirit

Assassination of a widely respected editor in Kashmir has sent shock waves across the Indian subcontinent

Shujaat Bukhari, the most prominent Kashmiri to be assassinated in the last decade-and-a-half, was a fellow journalist. He had an extraordinary quality to connect with people, which endeared him to all those he came into contact with. During our last encounter, earlier this year, I pointedly asked him if the relentless trolling, abuse and threats he received were taking a toll on him. Smiling tenderly, he quipped: “Fear, to an extent, is born of the story we tell ourselves.” All those fears came to a head last Thursday as Shujaat lay dead in a hail of bullets outside his newspaper office in Srinagar’s Fleet Street, along with his two personal security guards.

While alive, he dominated the media scene in the valley. Shujaat’s intimate knowledge of the intractable Kashmir conflict and the dramatis personae made him one of its most important voices. His articulation of the situation on the ground and fearless writing gained him scores of foes — across the ideological spectrum, which explained his role as an impartial editor. In time, Shujaat came to be seen as a primer of journalistic brilliance in the Valley and a rare ‘voice of sanity’. He took an active part in a series of peace-building initiatives on Kashmir as well as between India and Pakistan — a journey that took him to both New Delhi and Islamabad, and across the globe to London, Singapore, Dubai and Washington.

Somewhere along the road, this strong votary of Indo-Pakistan friendship ruffled feathers of the forces inimical to peace. Shujaat was unabashed about who he was — an advocate of Inter-Regional dialogue. He seemed to care about — and I noticed this in the deep conviction he had — Kashmir, its governance structures, human rights, civilian killings, water issues and culture. It is hard to tell if it was his capacity to build rapport with those he disagreed with or the relative ease with which he glided through the tricky political tangle of Kashmir that became his undoing. Clearly, the assassins, who seemed to have plotted the strike meticulously, were unnerved by Shujaat’s willingness to discuss ideas so fearlessly.

Peace activist at heart

Always elegantly turned out, with an infectious smile, Shujaat made it to the top of the media echelon in Kashmir during three decades of path-breaking journalism. Starting out with the fiercely independent Kashmir Times, he went on to be the Srinagar correspondent for the Hindu, later becoming the paper’s Srinagar bureau chief. He wrote commentaries in various national and foreign news outlets, including the BBC and represented Germany’s Radio Deutsche Welle. Shujaat started his own English daily Rising Kashmir, which, along with its sister publications, Buland Kashmir, Sangarmaal and Kashmir Parcham continue to be among the finest newspapers in Kashmir. Not surprisingly, his newspaper’s office was a magnet for literary and cultural activists.

Born in Kreeri, a serene village in Baramulla, Shujaat was a recipient of the World Press Institute (WPI) US fellowship and Asian Centre for Journalism, Singapore fellowship. He was also a fellow at East West Centre in Hawaii, United States. He is survived by his wife Tahmeena, a doctor, and two minor children — daughter Duriya and son Tamheed. Shujaat’s elder brother Syed Basharat Bukhari was a minister in the state government. His father, professor Syed Rafi-u-Din Bukhari, is a noted academic and litterateur. Shujaat had suffered a massive stroke in December 2015 and remained hospitalised for three months at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi, but made a full recovery and soon rejoined efforts towards creating a middle ground in Kashmir. At ease with both mainstream politicians in Kashmir and Delhi as well as leaders of the Hurriyat (Kashmir’s secessionist amalgamation), Shujaat strove to engage in dialogue. At heart, he was a peace activist.

Understanding nuance in Kashmir

Sadly, Kashmir, for all its natural beauty, can be an unforgiving place. As India and Pakistan continue to bicker over the final political status of the state, those seen as advocating reconciliation often run the risk of being labelled as anti or pro status-quo. Previously, top Kashmiri leaders such as Mirwaiz Maulvi Farooq (1990) and Abdul Gani Lone (2002) had met with violent ends because of their ideological or political leanings. Not surprisingly, Shujaat was often attacked by extreme voices on both sides of the divide — for his impartial work and nuanced understanding of the Kashmir question.

Trolled by the rabid right wing on Twitter recently, he was quick to retort: “In Kashmir, we have done journalism with pride and will continue to highlight what happens on [the] ground.” Friends and well-wishers would often caution him to keep a low-profile and avoid the polarised, toxic echo chambers of social media, but he remained undeterred. Minutes after this last tweet, which was about the United Nations General Assembly overwhelmingly passing a resolution over clashes in Palestine, Shujaat was dead, shot multiple times by unknown assailants at Press Enclave in the heart of Kashmir’s capital. Hours later, the UN tweeted out that it was ‘terribly saddened by the death of Shujaat Bukhari’.

While tributes poured in from Kashmir (from all sides of the political divide), India and Pakistan joined in offering their condolences to this brave, amiable scribe who had championed a peaceful solution to the Kashmir conflict for decades. Local journalists in Kashmir, some of whose careers he helped shape over the years, mourned him along with their counterparts in the Editors Guild of India — a body that oversees press freedom in the country. Even in death, as in his lifetime, Shujaat (Arabic for courage) very much remained a unifying force.