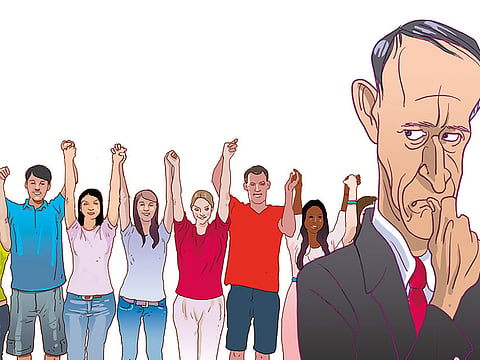

The generation gap is back — but not as we know it

There is an ideological conflict brewing between ‘woke’ millennials and an older generation, a conflict where neither understands the other

For a while there, in the first part of the new millennium, the generation gap was pretty much assumed to be dead.

People in their 40s shopped in the same clothing stores as people in their 20s, and listened to the same sort of music.

If you were on the Left, you all cheered for Barack Obama, and everyone from those in university dorms to the corner office had the Shepard Fairey posters of HOPE, and all ages were engaged in common political struggles (No invasion of Iraq! No blood for oil!).

You’d go to a Bloc Party concert and there’d be a finance dude there in his 40s wearing the same Urban Outfitters jeans as the child in his or her 20s, and everyone from the 19-year-olds to those high 37-year-olds leaving the dinner parties would end up at the same late-night bars.

According to an article on the merging of generations in 2006 in New York Magazine: “This, of course, is a seismic shift in intergenerational relationships. It means there is no fundamental generation gap anymore. This is unprecedented in human history. And it’s kind of weird.”

For the younger generation, how to rebel? How to mark yourself as different? Did age even mean anything anyway?

It’s 2018, and if you were a five-year-old in 2006, being rocked to sleep by your hipster dad singing you Arctic Monkeys, then you’d be 17 now. The same age as the Parkland children — who many are characterising as a “new generation” (this label has been applied to the Parkland children by outlets including the New Yorker, the New Republic, Christian Science Monitor and Salon).

Those who are a couple of years older are entering workplaces and colleges — and you know what? There is a generation gap — just not in the way that we imagined it.

It’s not about style. It’s not about taste in music (“Turn down that racket!”). It’s about language and battles over inclusivity, diversity and power structures.

And it’s a whole lot more complicated and confusing than the generation gaps of yore — where the olds were horrified at the Beatles and their long hair.

A new conflict?

Boots on the ground — what does the new generational conflict look like? Inside the newsroom at the New York Times there is an ideological conflict brewing between the old guard and the “new woke” employees. An article published last week in Vanity Fair titled “Journalism is not about creating safe spaces’: Inside the woke civil war at the New York Times” illustrates the tensions.

In the newsroom, the battle lines are being drawn around older hands who believe in reporting a diverse range of views (including those that the Left may find offensive), and who think that the reporting of the Donald Trump presidency should be fairly straight down the line. The younger generation was appalled at the 2016 election results and has expressed grievance at the Times hiring for their opinion pages one writer who has expressed scepticism about climate science and a millennial who supports campus free speech.

Other grievances within the newsroom that Vanity Fair reports as being split along generational lines include reaction to a reporter being allowed to return to work (in a demoted capacity) after being accused of sexual harassment and the managing editor, Dean Baquet, appearing at the same Financial Times conference as Steve Bannon — the former White House chief strategist.

According to the Vanity Fair piece “as at many newsrooms and media offices, and in the culture at large, this is a moment of generational conflict not seen since the 1960s”.

In Australia this conflict includes debates around who gets to tell what stories. For example — whether a fiction author has the right to depict an experience that is not her own (so a white Australian woman writing the experiences of a queer Indigenous man).

This issue came to a head at the 2016 Brisbane writers festival — where novelist Lionel Shriver gave the keynote address and argued that novelists should be free to write from the point of view of characters from other cultural backgrounds. In the audience was the writer and engineer Yassmin Abdel-Magied, who found the speech offensive and walked out.

She later wrote for Guardian Australia on the experience: “It’s not always OK if a white guy writes the story of a Nigerian woman because the actual Nigerian woman can’t get published or reviewed to begin with.

“It’s not always OK if a straight white woman writes the story of a queer Indigenous man, because when was the last time you heard a queer Indigenous man tell his own story?

“How is it that said straight white woman will profit from an experience that is not hers, and those with the actual experience never be provided the opportunity?”

Or it shows up in a reconsideration of the work of Chris Lilley — once a Gen X icon for Summer Heights High and We Can Be Heroes, but now being chastised and on the nose for depictions of characters such as Jonah from Tonga.

The show did not go down too well with critics in the United States and United Kingdom — with the Huffington Post describing Lilley as “a 39-year-old white guy in a permed wig and brownface. Yes, brownface. In 2014”. Yet, when Summer Heights High first aired in 2007, the brownface went largely unremarked upon.

Last week, it was The Simpsons that came under fire for its flip response to anger over the depiction of the long-running Indian character Apu (Lisa says “Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?”)

Part of this gap between young and old is the rise and mainstreaming of identity politics and intersectionality, a theory originating in black feminism, that calls out identity-based oppression.

This theory, around since the late 1980s and 1990s and used to describe interlocking and structural systems of power, was coined in 1989 by the academic Kimberle Crenshaw. It is used to describe, in Crenshaw’s words, the “multiple avenues through which racial and gender oppression were experienced”.

So how a black hotel cleaner might experience workplace discrimination is different from how a white, upper-class lawyer might experience it — because other forces of oppression are also at work other than gender discrimination.

Intersectionality was once a notion confined to the campus — its concerns did not reach the editorial conference room in the newspaper, in the programming of a music or writers festival, or the writers room of a TV sitcom.

But in recent years, it has jumped off the page and into real-life discussions about #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, for example.

Back in 2006 — when the generation gap was pronounced deceased by New York Magazine (and a year before Jonah from Tonga was shown on Australian television to an accepting public) — words associated with this movement such as no-platforming, the use of “a violence” as a verb, and woke as an adjective, microaggression, and cisgender heterosexual either did not exist, or had not entered the mainstream.

The woke generation (young millennials aged between 18 and 30) brought the theories of intersectionality and identity into debates about a range of human rights issues: Campus free speech, trans rights, the Me Too movement, marriage equality, gun control, reproductive rights, Black Lives matter and, in Australia, the Change the Date movement.

This new way of looking at the world has resulted in a golden age of protest, dissent and pushing back against societal norms. Marches in the United States — such as the women’s march and the one for gun control — have smashed attendance records, while in Australia, the Invasion Day march surpassed all expectations of crowd size.

The landscape has shifted dramatically in the past few years, and older people (on the left and right) have found that they have been tripped up and called out by their more woke colleagues or friends or Twitter followers.

(the Wall Street Journal, in a piece last week, somewhat gleefully predicted it would be those who policed “wokeness” who would destroy the Left).

Left-leaning Gen Xer’s thought that by listening to Rihanna, skateboarding to work and going to Coachella, they could defeat the generation gap. Now they are grappling with the idea that they may be causing offence — sometimes inadvertently — through a tweeted microaggression or an offensive Halloween costume or sombrero worn at a tequila party or a positive comment about Bill Leak’s legacy or personality on Twitter after he died.

The response — at least online — is punitive if offence is caused.

According to the piece in New Yorker on the new campus politics — it’s “flummoxed many people who had always thought of themselves as devout liberals. Wasn’t free self-expression the whole point of social progressivism?”

This is a generation gap — it’s just unlike any other we have seen before.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Brigid Delaney is a senior writer for Guardian Australia. She is the author of two books: This Restless Life and Wild Things.