China is exporting authoritarianism as the West’s power to stop it declines

In Zimbabwe and beyond, the best hope is to reform the West’s own politics to set an example worth following

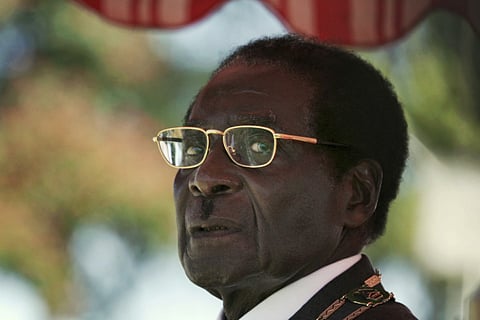

One of the minor successes of my time as foreign secretary was that I managed never to meet Robert Mugabe, despite having to sit only a few feet away from him at the United Nations General Assembly. A predecessor, Jack Straw, was severely embarrassed after shaking his hand and was reduced to the much-derided excuse that it had happened in a darkened room. Since I was required to meet many of the world’s despotic, power-crazed autocrats, giving Mugabe a miss was a relief.

Mugabe has demonstrated once again the truth that while the power of government to do good is limited, its ability to cause harm is infinite, bringing poverty and hyper-inflation to a country rich in natural resources and human talent. When he is finally dragged from the presidency, Zimbabweans will be entitled to a moment of hope — that their country can be led in a different way, consistent with democracy, freedom and prosperity.

Many of the bravest of them have struggled for that for decades. The United Kingdom can help them. We have long had ready a worked out plan to give major aid once the country is free of corruption, embezzlement and tyranny. Yet, we have to recognise that our own efforts to support a more democratic Zimbabwe will be based on hopes rather than decisive influence, and that there, and in many other countries, there are powerful forces who either tolerate authoritarian leadership or seek it. The most likely successor to Mugabe, Emmerson Mnangagwa, has played a full part in the incompetent and blood-soaked story of the last 37 years.

Significantly, before the military chiefs ordered the tanks to roll last week, it was from Beijing that they apparently sought a green light, rather than London or Washington. If so, the Chinese leadership gave the right answer, but it is a sign that external power over African affairs is steadily moving in their direction and away from the West. All over Africa, there are foreign ministries, presidential palaces and infrastructure built with help from China.

There is nothing wrong with that in principle, except that such aid comes with few qualms about poor governance, absence of democracy and serious violations of human rights. The age in which westerners could assume that more countries would naturally adopt systems of government similar to their own is over, and the age in which they could require some of them to do so is coming to an end as well. Turkey is a key example of this, moving in just a few years from seeking to demonstrate the standards of a European democracy to caring little about the remonstrations of the West as authoritarianism takes hold. And after Iraq and Afghanistan, there is little chance of the United States invading many other places to build a freely governed nation from a scratch.

In Britain, we all take comfort in Winston Churchill’s maxim that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others”, and we share a lazy confidence that others will always find this to be so. But for the first time since the end of the Cold War, some of the most powerful figures in the world are prepared to challenge this thinking.

The speech of Chinese President Xi Jinping last month to the Communist Party Congress was of vast importance to the future of ideas and power in the 21st Century. Not only did he declare that China would be ready to take “centre stage” in world affairs by the middle of the century, with “world-class” armed forces, he also argued that “socialism with Chinese characteristics ... offers a new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence”.

In other words, the Chinese model of one-party state-led capitalism, with tight ideological control and the use of the new digital economy to enforce citizens’ loyalty, is ready for export to other nations. What is more, those nations can avail themselves of it without having to bow to the lectures of westerners about governance, rights and debt repayments. The way will be open to dictators breathing more easily.

In a quarter of a century, we will have gone from US presidents being messianic about spreading democracy, to a re-born Communism ready to grow again and a US president not exactly motivated by the march of freedom. This does not mean that all is lost.

There are African nations that have entrenched their democratic habits and even insisted on them among their neighbours, as the intervention of west African countries in The Gambia showed. But as more power passes to the East, the ability of what we used to call the “free world” to bully tyrants with sanctions, embargoes or the threat of invasion is receding. And battered by globalisation and populism, with Russia highly active in fomenting discord within western electorates, our trust even in our own democratic institutions is diminishing.

So what do we do? Of course, we have to strengthen our ability to protect ourselves from both military and cyber attack. Crucially, however, a reduced ability to lead by muscle and force means we have to lead all the more by the power of example. If you can’t make people do what you want, you have to rely even more heavily on inspiring them to do it anyway. That means that if others reduce their standards of respect for human rights, we must refuse to do so.

Most importantly, we have to renew the health of our own democracies. In Britain, that involves a flow of new ideas from the centre of politics — from Blairite Labour to most Tories and Liberals — about education, housing and the environment. It should mean taking the opportunity of Brexit to reform parliament to give better scrutiny to laws, and making a success of devolving powers to cities.

It will need a radical change to the regulation of social media, forbidding political advertising and foreign influence, and requiring greater balance and diversity in the news. The persistent feeding of prejudices and prevalence of “fake news” are serious threats to free political choice. The slow-motion fall of Mugabe, then, is not just a satisfying conclusion to an agony in a faraway country. It will be another test of which ideas are gaining ground in a gathering struggle — one in which we will need to reform ourselves to win.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

William Hague is the former UK foreign secretary and a former leader of the Conservative Party.