Why ‘We Don’t Know Ourselves’ is the year’s best book

A masterpiece by a gifted storyteller — Fintan O’Toole — at the height of his powers

On we go, entering the stretch, mere days before we round the corner into 2023, time for this columnist to reveal his choice for the “Best of the Year” book, an emotionally punishing task for a bibliophile who finds himself torn having to pick among two, three or even four books that had enthralled him in equal measure.

I choose a book rather than a film to review every year because, well, very simply, I swing more as a bibliophile than a cinephile and I just happen to find words more magical in how they depict objective reality on the printed page than images do on the silver screen.

“I don’t believe in the kind of magic found in my books”, wrote J.K. Rowling, a wordsmith who you surely will agree knows a thing or two about magic. “But I do believe something magical can happen when you read a good book”.

Also Read: America First populism is here to stay

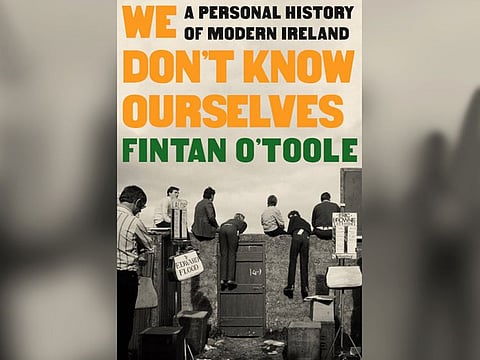

I can tell you that something magical happened to me when I read Fintan O’Toole’s “We Don’t Know Ourselves”, whose subtitle — hold on to your hat as you scratch your head — is “A Personal history of Modern Ireland”, a book in which the author deftly interweaves six decades of modern Irish history with his own life story — and does it with the literary elan and sly humour we have come to expect from Irish writers.

Look, maybe I should’ve recused myself from reviewing this book in the first place. because I am biased. And I am biased because I’ve always been, as a Palestinian, fond of the Irish people — for whom Palestinians had traditionally evinced great empathy and with whom, lest anyone forget, they had at one time shared the same English coloniser — fascinated as I was by their struggle for survival, especially that one harrowing struggle that stretched from the Great Hunger to the Easter Rising.

The Great Hunger (also known as the Potato Famine) was of course that 4-year period of starvation and disease that began in 1845, during which roughly a million Irish men, women and children died and more than a million fled the country, most to the New World.

And the Easter Rising, in April 1916, another equally well-known turning point in Ireland’s history, was the intifada mounted by Irish Republicans against British rule, which finally led to Irish independence four years later — albeit minus the six counties of Northern Ireland.

Historical archetype

This is the historical archetype of which Fintan O’Toole is the product. But “We Don’t Know Ourselves” is not about any that, except in context.

Rather, O’Toole, a veteran Irish American journalist, drama critic, author and book critic (mostly for the New York Review of Books), traces the “personal history” of Ireland from 1958, the year he was born there, to the present. “My life is too boring for a memoir and there’s no shortage of books on modern Irish history”, he writes. “But it happens that my life does in some ways span and mirror a time of its transformation”.

And what transformation has Ireland gone through that year!

In 1958, Ireland was an impoverished country and, as he writes, with a touch of irony, “suffocatingly coherent and fixed ... shielded from the unsavory influence of the outside world”, a country that, come to think of it, was not much like the England of 1958 — where I was attending my last year of high school — whose people, I could see for myself, still moved around the treadmill of immemorially posited norms and fixed perceptions of class, status and privilege, content to embrace the adage that there was in a society a place for everyone and everyone was in his place.

The Ireland of 1958, that O’Toole sees through the prism of his own life, then still functioned as a cooperative between church and state, where the latter exercised disproportionate power over the workings of social life; homes in rural areas had no plumbing; hand-drawn wagons delivered milk to homes in Dublin; and the country had to wait for another three years to launch its first television station — only three before Bangladesh.

Yet today Ireland is a modern, prosperous nation, partnering with other countries in the European Union in cultural, political and economic transformations that began to sweep across the Continent in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Stylistic elan and laid-back pace

Indeed, that partnership has been so transforming that in our time, Ireland, a small nation of five million people, is considered, in terms of GDP, one of the wealthiest nations in the world — save for that puncture in the dialectic, as it were, when the country was buffeted by the ill winds of the worldwide economic crisis of 2008.

In effect, the Ireland of 1958 bears little resemblance to the Ireland of 2018, the year the author, we are told, sat down to pen his personal history of what Irish emigres like himself call the “auld sod”, and the rest of us engagingly call the Emerald Isle — which is what Irish poet William Drennan first called it in his 1795 eve-of-rebellion poem “When Erin First Rose”.

It may be that by reading this book, as a reviewer in the New York Times put it, “You will be educated, yes ... but you’ll also be entertained by a gifted raconteur at the height of his powers”. And it may be that, additionally, you will be enchanted by its stylistic elan and laid-back pace.

But the book brings more with it — more than a “personal history” of modern Ireland. It brings us no less than a narrative history of a nation, a people and a struggle, an inner history whose poetics O’Toole plumbs and shares with us.

A non-fiction book is expected to steer clear of affect and abide by the gospel of objectivity. Not this book. Not this Irish writer who knows how to speak to, about and from the inner history of his people.

Part of what it means to write well as an engaged writer is, as the Romanian-born poet Alina Stefanescu, who lives in Birmingham Alaba, put it, to remember that “Often we write from what is held in-common: a wick, a spark, a shared darkness, a contiguous reverence — the erotics of intellectual inquiry”.

And Fintan O’Toole has shown us in his book, without reservation my pick for best book of the year, that he has done all that — and then some.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, academic and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.