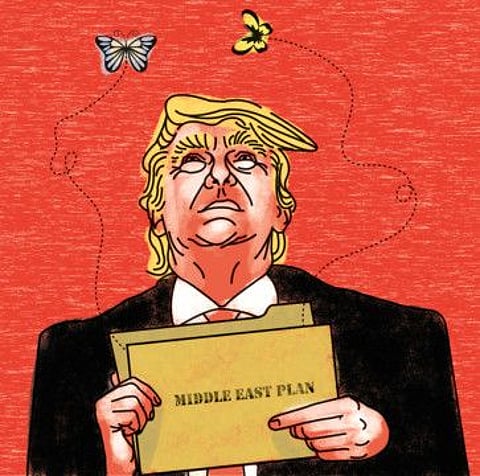

Trump’s plan for the Middle East not coherent

A strategy based on lack of clarity seems like a bad way to advance US national interest

Over the weekend, two facts came through in all the reporting about the administration’s approach to Iran. The first is that this is not President Donald Trump’s first-generation national security team. That group, including Jim Mattis and Rex Tillerson, would occasionally push back on Trump’s foreign policy instincts.

Not this bunch. The Associated Press reported, “Administration officials, at least for now, point to a new camaraderie in the latest incarnation of Trump’s national security team: [Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo and Defence Secretary Mark Esper were US Military Academy classmates; Army Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has grown close to Trump; and [national security adviser Robert] O’Brien, unlike [former national security adviser John] Bolton, has not tried to pull an end run around others in the decision-making process.”

The second fact is that this group of like-minded individuals is having a difficult time getting on the same page about why the United States killed Qassem Soleimani. The answer “because he’s a bad guy” does not cut it — there are plenty of bad guys in the world and the United States kills very few of them. The administration’s rationales have been all over the map on this over the past 10 days.

The State Department warned that the US could shut down Iraq’s access to the country’s central bank account held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a move that could jolt Iraq’s already shaky economyDaniel W. Drezner

The claim of an “imminent threat” seems iffy: The New York Times reported on January 12 that “a State Department official has privately said it was a mistake for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to use the word ‘imminent’ because it suggested a level of specificity that was not borne out by the intelligence”.

Trump’s red lines?

So this very unified national security team is not quite believable. This lack of clarity might help explain why an ABC News/Ipsos poll shows that a majority of Americans feel less safe after the attack. After the past 10 days, I have a basic question: What, exactly, does this administration want to accomplish in the Middle East?

I ask because of this presidential tweet: “National Security Adviser suggested today that sanctions & protests have Iran ‘choked off’, will force them to negotiate. Actually, I couldn’t care less if they negotiate. Will be totally up to them but, no nuclear weapons and ‘don’t kill your protesters.’”

So are these Trump’s red lines? Because it seems very likely that the Iranian regime will violate one of them quite soon, because Iran’s security forces are using live ammunition to quell protests. And on the nuclear question, it is factually undeniable that Iran is closer to developing a nuclear weapon now. Maximum pressure might weaken the Iranian economy, but it has accelerated the Iranian nuclear programme.

If the Trump administration’s position on Iran seems confusing, its position on Iraq is even more puzzling. For a president who has repeatedly stressed his desire to get US forces out of Iraq, his administration sure seems not to have received the memo. The Washington Post reported, “The Trump administration refused again to recognise Iraq’s call to withdraw all US troops, saying that any discussion with Baghdad would centre on whatever force size the United States determines is sufficient to achieve its goals there.”

The Wall Street Journal reported on January 13 that the administration has gone so far as to threaten economic sanctions against Iraq if Baghdad insists on a departure of US forces: “The State Department warned that the US could shut down Iraq’s access to the country’s central bank account held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a move that could jolt Iraq’s already shaky economy.”

Power rivalries

What is truly bizarre about all of this is seeing all this effort take place in a region that the Trump administration’s strategy documents have de-emphasised. None of these moves assists the United States in its great power rivalries. At best, the Trump administration seems to be doing its damnedest to look like an imperial power.

Back in 2017, Walter Russell Mead explained that Trump’s triumph represented a Jacksonian revolt against foreign policy elites who had gotten the United States embroiled in Middle East conflicts. Jacksonians mostly want to be left alone by the rest of the world, but react strongly against perceived threats.

In theory, this allows them to escalate and de-escalate quickly. In practice, the Trump administration keeps sending more and more troops to a region that Trump disdained throughout his 2016 campaign. The administration reacts to requests to leave with angry sanctions and stubborn refusals.

What does this administration want in the Middle East? Damned if I know. All I am sure about in 2020 is that a grand strategy based on spite seems like a bad way to advance the national interest.

— Washington Post

Daniel W. Drezner is a professor of international politics at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.