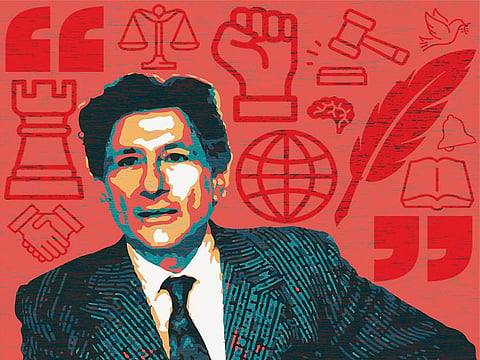

Remembering Edward Said’s world 20 years on

In the scholar’s voice Palestinians hear an echo of their preoccupations as a people

Death ends the life of a great thinker but not the legacy he leaves behind. And so it is with Edward Said, whose iconic book “Orientalism” (1978) is universally recognised, according to Britannica, as “one of the most influential scholarly books of the 20th century” — a well-deserved tribute to an extravagantly rich and intently provocative work that critiqued, challenged and then went on to transform the very paradigm on which post-colonial studies were anchored.

September 25 marked the second decade since the passing of Edward, or Edwa’ar, which is the way his name is pronounced in Arabic and the way he preferred to be called by us, his Palestinian friends in the United States.

My first encounter with Edwa’ar took place when I still lived in Paris and had just flown from there to the US in the summer of 1972, where I was to go on a lecture tour to promote the release of my first book, “The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile”. We met in New York at a dinner party arranged by our mutual friend Fayez Sayegh, a towering figure in Palestinian intellectual circles who, among other things, had taught philosophy, his discipline, at Harvard, Princeton and Oxford.

First encounter with Edward Said

It was clear from the get-go that evening that Edwa’ar didn’t like me much, I presumed because I kept insisting, indeed harping, on the wisdom (which I had articulated in a chapter in my book) of Palestinians, then and there, aiming to embrace the idea of a separate state in the West Bank and Gaza, with East Jerusalem as its capital, and giving up the pipedream of a “secular, democratic state” in the whole of historic Palestine. At the time, there were a mere handful of colonists in the occupied territories. (To be sure, that chapter did not then endear me to a lot of other Palestinians, to whom the idea then was taboo, if not altogether treasonous.)

And come to think of it, I didn’t like Edwa’ar either. I thought he was too uncompromising in his views about what should constitute the right solution to the Palestinian problem and the practical political programme that the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation) should have formulated. I was, after all, Ibn mukhayammat, or “son of the camps”, a Palestinian who grew up in a refugee camp, made his original leap to a maturing consciousness there and endured unspeakable suffering as a diaspora Palestinian. In short, no one was going to pull rank on this kid when it came to the question of Palestine.

He [Edward Said] was a down-to-earth intellectually inquisitive individual who earnestly wanted to explore those aspects of the Palestinian experience he had not lived through, growing up as he did in a privileged milieu.

But guess what? It’s not true that you don’t get a second chance to make a first impression.

Edwa’ar and I soon met again, and yet again and again, when I finally arrived in the US the following year to live there permanently. This time the chemistry was there. And it all began with me thinking of him simply as a brilliant intellectual from New York — and I call him that now to distinguish him from that gaggle of writers, literary critics, poets and belle lettrists known as “New York intellectuals’’, young men (mostly men) who had been active in the city since the 1950s, embraced leftwing politics and sought to integrate literary theory with a Marxist view of the world while eschewing Soviet socialism.

But then, in later encounters, in later years and in later tete-a-tetes, I discovered that Edwa’ar was more than an intellectual from New York, albeit a brilliant one. He was a down-to-earth intellectually inquisitive individual who earnestly wanted to explore those aspects of the Palestinian experience he had not lived through, growing up as he did in a privileged milieu.

What was it like, he so wanted to know, to grow up in a refugee camp; how was I able to deal with my sense of otherness living there; why as a diaspora Palestinian was I able to continue clinging to my identity, all these years, in all these countries I had inhabited as an exile? And so it went. He evinced the same impassioned inquisitiveness about the idiom and metaphor, the mysteries and ambiguities that animated Palestinian lives lived differently from his own.

Life in a Palestinian village

And that was evident when he encountered Palestinian poet Rashid Hussein, who at the time lived in New York and was born and had grown up in a village in northern Palestine when the country was under British Mandate rule. (Hussein was a year younger than Edwa’ar.)

What was village life like there, he wanted to know, what was the role women played in village culture, and what kind of socialisation process were kids subjected to? (Hussein, who was a friend, drank more than he cared to admit and ended up dying one night in 1977 with a lit cigarette in his hand, after a fire broke out in his apartment.)

It was around that time, as we read in Timothy Brennan’s masterful biography, Places of the Mind: A Life of Edward Said, that Edwa’ar began to make the shift from his perch in the ivory tower as a cloistered academic, writing books like Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography and Beginnings: Intention and Method, to the moral urgency of engaging the world as a Gramscian “organic intellectual”, focusing on the themes that later informed “Orientalism”.

Who wants to be a literary critic?

In an interview in 1992, he vented his frustration as a literary critic reading literary journals published by humanities departments at several universities, such as Critical History and Diacritics (seriously, humanities departments at several universities do publish journals with names like that), telling the interviewer, “It seems to me that whereas, say, ten years ago I might have eagerly looked forward to a new book review in Crit-Di, written by someone at Cornell [University] on literary theory and semiotics, now I’m much more likely to be interested in work emerging out of concern with African history”.

Oh, yes, who, I say, would want to be a literary critic when they can be an organic intellectual? Aren’t there more interesting, not to mention more existentially pressing things to attend to in life?

Literary criticism may not be — not by a stretch — a trivial pursuit, but it is, at the end of the day, an accessory, for what a literary critic does at the end of the day, as George Steiner, himself the dean of literary critics, put it, is to bring a work of literature to the attention of precisely those readers who may least require it. And, let’s face it, what reader would peruse a critique of poetry, drama or fiction unless he or she is already highly literate?

Edward Said would not have any of that.

Also Read: Fox News comes to Saudi Arabia

Several years before his death, before email, Edwa’ar sent me a short, handwritten letter congratulating me on the publication of my fifth book, “Exiles Return: The Making of a Palestinian American’’, and asked at the end of it, “And how’re you doing these days?”

Not very well, thank you.

I kept that letter. A letter from a friend whom countless people around the globe paid homage to the day he passed 20 years ago, on September 25, 2003, a man whose legacy will continue to have a mastering grip on the sensibility of intellectually engaged people worldwide, and in whose voice Palestinians everywhere hear an echo of their inward preoccupations as a people.

Remain resting in peace, brother Edwa’ar.

— Fawaz Turki is a noted academic, journalist and author based in the US. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.