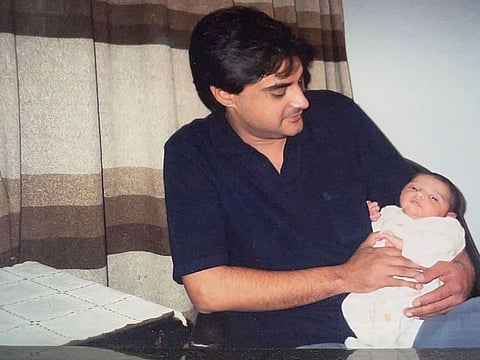

My Brother Babar

'I don’t write about Babar’s death because my words acquire a redundancy when I try'

Scrolling down B in my WhatsApp contact list yesterday, I stopped at Babar. Two numbers that were without a chat, two numbers that had not been dialled for a long time. They will never be dialled. It was pain that took my breath away. Time doesn’t heal, the re-realization was abrupt, scary.

Babar. Babari. My beautiful brother who left us on March 18, 2019. Without any notification, death took him away from us. Losing my mother on November 6, 1999 was the biggest tragedy of my life full of things I wish I could erase from my soul. Babar’s passing redefined pain. Losing a younger sibling felt like severing of a limb without anaesthesia. Losing my baby brother was unimaginable hell. Losing Babar is the pain without any remedy.

I don’t write about Babar’s death because my words acquire a redundancy when I try. Even today, I know what I’m writing is disjointed. How do I make sense of something that changed my life forever? Whenever I read a date anywhere, the first thing that I notice is the month and the year. For me, the world seems to have divided into two periods: before and after March 18, 2019. Life wasn’t rosy before that date, but it was never this dark. The after-Babar life is perpetually shaded in his absence.

My closeness to my younger siblings is as old as their existence. Our parents separated when Babar was born, and our entire childhood was our despair at being forced to live away from our mother and siblings. In our village where our mother lived with her mother, it was Babar, her youngest child, who she was closest to. Babar lived with her, in the village and later in Lahore, until she passed away. Her three children—my older brother was in boarding school in Lahore, and my sister and I were in Sargodha with our paternal grandmother—visited her in school holidays. Watching his mother exist in her drab, cheerless solitude shaped Babar in ways that he questioned things all his life. Our mother’s pain haunted him for as long as he lived.

They died twenty years apart, but they are buried next to one another in a graveyard in Lahore. My mother and my brother. They left the world without ever experiencing real lasting happiness. When I visit their graves, I marvel at the strength of their love for one another. Even in death, they are together. I stare at their tombstones, standing side by side. The mother and her son. Their graves are joined under one piece of marble separated by two rectangles of mud. Rectangles that are weekly covered in rose petals. There is no place that is more painful for me. There is no way I could not visit it.

I talk to them. I tell them I’ll be back. I leave them saying see you soon. The ghosts of their pain haunt me.

When I talk to my nephew Taimur, my brother Babar’s only son, I feel a sense of indescribable peace. We rarely talk about his father, but he is present in all our conversations. Like his father, Taimur loves clothes and colognes, and is always impeccably dressed. He looks so much like his father it’s almost comforting to see his face. That Babar is still here. In the form of his son who has so many of his amazing qualities—selfless love for his family, empathy, a giant heart.

For Babar, Taimur was the most important person in the world. He lived for his son. Taimur lived with his mother after his parents’ divorce but he spent a great deal of time with his father. Taimur once said to me, “I used to imagine that when Baba is old and is on a wheelchair, I’ll give the world to him.”

There was no one in our family who didn’t love Babar. His friendships were lifelong. Babar adored children, and they adored him. The most heartfelt mourning at his funeral was a testament to people’s grief at his loss. Everyone who truly knew him loved him.

Listening to Kishore Kumar songs is the instant memory of the sounds from Babar’s room. We lived in the same house since 2008, and his room was across my son Musa’s. Babar’s love for music started in his childhood, and he loved to sing. In the last years of his life, he used to share Arijit’s songs with me. Now so many lovely songs are terrifying reminders that my brother is gone. Forever.

Babar’s life was a series of treatments and surgeries after he was tortured in police custody at the age of eighteen. His backbone was permanently damaged. My brother, a star horseman and athlete, spent most of his adult life in agony. There were periods of partial and complete recovery, but they didn’t last long. For as long I’m alive, the knowledge of his misery won’t let me rest. One of his legs was almost paralysed. In March 2019, we found a wonderful doctor and asked him to see Babar at the earliest. The appointment was set for March 20, 2019. Two days after Babar passed away.

My brother had been unwell for a few days—fever and acute weakness. He was bedridden. But it was nothing that was untreatable. Refusing hospitalization, he was content with a male nurse giving him doctor-prescribed injections and IV drips.

The day he left, Babar was a bit of his old self. One thing he said that day was that he was tired of being in Lahore, and that he was going to his village.

Talking about Babar is easy. My sister and I often talk about him. Thinking about him in the solitude of my room is poking a hole in my heart. Writing about him is pure agony. Was. Passed. Gone forever. Funeral. Grave. Tombstone. My late brother. Anything about him in written words is a knife in my gut. But I owe him a few words. This is not his obituary. This is unfiltered pain of his grieving sister. Suppressing my howls, through my constant tears. I feel a stone pressing on my body, right above my heart.

Today I remember the words of my son’s friend about her mother’s loss: “The circle of grief never gets any smaller, instead we grow larger around it.”

There is so much that I remember about my brother. Three pillows on bed when he was little, one for head, one on each side. His inability to memorise G for grapes. A toy car, known as a “dinky” to us, clutched in his hand, even when asleep. My sister and him fighting who would sleep with Ami. His obsessiveness about clothes to be perfectly wrinkle-free. His love for food, his love for desserts. Fearlessness to the point of recklessness. Stories of his boarding school. His tent pegging at school and at Lahore’s annual Horse and Cattle Show. Lack of interest in studies. Generosity that was excessive. Diabetic in his early twenties. His favourite Ferrero Rocher and labelling the boxes of chocolates in fridge: do not eat. Falling in love and staying in love. Loving his nieces and nephews like they were his own children. Giving up his bad habits so that his son was not embarrassed of him. Loving his son without judgments, without conditions. The gorgeous smile softening his perfectly formed face.

My brother Babar, like all of us, was not perfect. He continually damaged his already deteriorating body. His anger created countless divides between him and those he loved. For all that, he paid a heavy price. Yet in spite of his vices, he is remembered by his family with only the purest love and the deepest compassion. He was the strongest person any of us knew. His pain, always hidden.

We were complacent too often. Our minds on more important things, too often. I would give anything in the world to just have spent one of those days that Babar and I spent arguing just sitting with him. Maybe reminiscing, maybe watching a movie, maybe doing nothing at all, but sharing a moment in time with one another.

I miss my brother. I want to say so much to him. So many things left unsaid. So many hugs that I didn’t give him. So many sorrys that remained un-worded. So many things he didn’t do with his son. So many incomplete plans. So many unfulfilled dreams.

As I read daily surahs for him and my mother and my nani, I pray to Allah to bless my loved ones with His best. May they have in heaven what they didn’t have in their lives.

My brother Babar is in in my heart, on my mind, in my thoughts, in my dua, in my what-ifs, in my now, in my tomorrow. What I wouldn’t give to tell him once: I love you, Babari. Let’s talk.

Three years, eight months, twenty-five days since Babar.

Till we meet again, mere bhai.