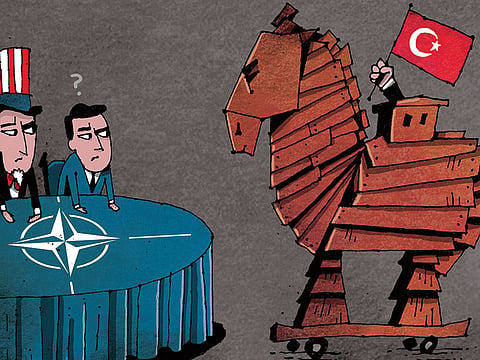

It’s time for Turkey and Nato to go their separate ways

There is no clear mechanism to expel alliance members it survival nonetheless requires purging Ankara

“If the internal stress in the US goes on like this, the possibility of another 9/11 is not all that remote,” wrote columnist Abdul Rahman Dilipak in Yeni Akit, a paper close to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his political party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP). Such threats and incitement may sound strange coming from a Nato member, but they have become the new normal in Turkey.

In 2004, Metal Storm, a fictionalised account of war between Turkey and the United States, shot to the top of Turkey’s best-seller list. The Turkish newspaper Radikal wrote that “the Foreign Ministry and General Staff are reading it keenly” and “all cabinet members also have it.” After a US-based energy firm began drilling in Cyprus’ waters in September 2011, Turkish Minister Egemen Bagis warned, “This is what we have the navy for. We have trained our marines for this; we have equipped the navy for this. All options are on the table; anything can be done.” More recently, Erdogan threatened US forces in Syria with an “Ottoman slap.” Both Dogu Perincek, an intellectual godfather of the Turkish military, and Adnan Tanriverdi, Erdogan’s military counsellor, are both fiercely anti-Nato.

Nor is Turkish hostility limited to words: Turkish nationalists have attacked American sailors when US ships are docked in Turkish ports. And AKP apparatchiks have demanded the arrest of US personnel based at Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base. Several American citizens, including the pastor Andrew Brunson, are already in prison on dubious national security charges.

It wasn’t always this way. Thousands of Turks fought alongside American forces during the Korean War. Turkey lobbied furiously for inclusion in the Western-defensive alliance. It was “imperative that democracies work in complete harmony, without competition among themselves or differences in policy objectives,” Foreign Minister Mehmet Fuat Koprulu told George McGhee, the US ambassador to Turkey, in January 1952, shortly before Turkey joined Nato.

And Turkey’s contributions to Nato have been valuable. If the United States was the alliance’s backbone, Turkey was its muscle: Even today, it has more men under arms than France and Germany combined. And not only was it one of only two Nato countries to border the Soviet Union, but it also served as a bulwark against radicalism and terrorism emanating from the Middle East.

But all that was before Erdogan. Does Turkey, today, still belong in Nato?

Matt Bryza, a former National Security Council official and deputy assistant secretary of state, argues against any turn away from Turkey: “Abandoning Turkey now would weaken Nato, forfeit US influence in the Middle East and threaten the coalition whose fight against Daesh [the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] is far from finished.” Likewise, former US ambassador to Turkey James Jeffrey and his colleague Michael Singh insist that “cutting Turkey loose would constitute a self-inflicted wound. Turkey is not just President Erdogan but a regional geographic and economic giant that stands as a buffer between Europe and the Middle East, and between the Middle East and Russia.”

Changed character of military

That all sounds good in theory. What Bryza, Jeffrey and Singh ignore, however, is just what 15 years of Erdogan has done to the United States’ former ally. In short, they confuse Turkey of yesteryear with Turkey today.

Consider Turkey’s military: Whereas the Turkish army was once a secular bulwark against Islamism, Erdogan has changed its character. Almost all the officers, up to lieutenant colonel, have spent their entire careers under Erdogan’s leadership. Erdogan has also used a series of fanciful coup plots to derail the promotion of professional and more secular officers so that he could appoint political sympathisers in their place. He purged almost anyone with any significant service in Nato: Even before the abortive 2016 coup, Erdogan had imprisoned one out of five generals.

The question of what Turkey might do if the United States cuts it loose is valid. But when Turkey’s proponents cite its importance in the war against Daesh, they neglect to mention that Daesh only thrived because Turkey allowed foreign fighters and equipment to cross its borders.

Writing in the New York Times, Erdogan himself warned that continued “disrespect will require us to start looking for new friends and allies,” an unsubtle threat that he might pivot toward Russia. But, in many ways, he already has. Erdogan has made it clear that he aims to purchase Russian S-400 missiles, which, if integrated into Turkish air-defence systems, might compromise Nato air-defence secrets to Russian engineers. Those counselling a softer line point out that Erdogan’s strategy is, in part, transactional. This is true, but that is all the more reason to second-guess Turkey’s role in collective defence. After all, when a crisis erupts, Nato members must rally together, not engage in bidding wars with Washington and Moscow over who deserves its loyalty.

Indeed, the real danger to Nato is not that Turkey will withdraw or pivot to Russia, but rather that it remains inside. Because Nato decisions are consensual, Turkey can play the proverbial Trojan Horse to filibuster any action when crisis looms.

It is true there is no clear mechanism to expel Nato members — but Nato’s survival nonetheless requires purging Turkey. The West should call Erdogan’s bluff.

— Washington Post

Michael Rubin is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute