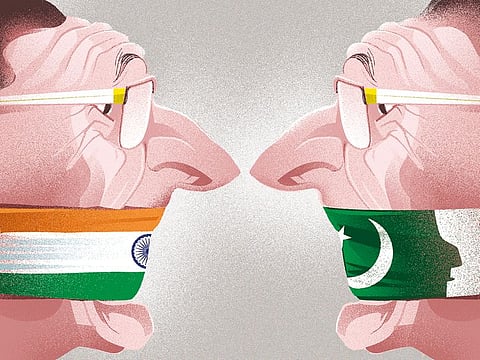

India, Pakistan waging war on their own media

The ruling classes in the Subcontinent have established an authoritarian mindset

Last month, India and Pakistan marked the centenary of an atrocity in which the British army opened fire on thousands of unarmed civilians in Jallianwala Bagh, a walled public garden in the Sikh holy city of Amritsar. The victims — a mixed crowd of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs — had gathered to protest against the Rowlatt Act, a draconian legislation devised by a British judge that allowed British officials to detain Indians without trial and to arbitrarily restrict speech, writing and movement.

The unprovoked killing of hundreds of demonstrators effectively launched the anti-imperialist struggle in British-ruled India, provoking Mohammad Ali Jinnah, father of the Pakistani nation, as well as Mahatma Gandhi, father of the Indian nation, into unstinting opposition to the British.

Predictably, the 100th anniversary of the massacre elicited much righteous self-regard among Indian and Pakistani politicians. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took time off from his hectic election campaign to tweet about the “martyrs” of Amritsar: “Their memory,” he wrote, “inspires us to work even harder to build an India they would be proud of.” Fawad Chaudhry, until recently Pakistan’s information minister, demanded an apology from Britain.

But anti-imperialist posturing cannot disguise the fact that India and Pakistan continue to expand the repertoire of legal repression they inherited from the British.

Quasi-Rowlatt acts are on the law books in both countries. In Pakistan, Cyril Almeida, an editor and columnist at Dawn, one of Pakistan’s most respected English-language dailies, is among several figures accused of treason and barred from leaving the country [last year].

Many journalists in Pakistan were killed or “disappeared” by the country’s security establishment during decades of misrule by military despots and venal civilians. The election of Imran Khan, a former sportsperson, as Pakistan’s prime minister last year was seen by many as inaugurating a “Naya (New) Pakistan.” His information minister has been busy devising a drastic regime of media regulation in Pakistan. Officials have blocked television networks and the distribution of newspapers, and forced media companies to fire journalists deemed too critical of authorities.

As Almeida, who was recently named the International Press Institute’s 71st World Press Freedom Hero, puts it, “Press freedom in Pakistan is under severe and sustained attack, without precedent during eras of civilian governments and the worst in the country since an oppressive military dictatorship in the 1980s.”

Conditions for journalists are not much better in neighbouring India. In the latest global press freedom index compiled by Reporters Without Borders, the world’s largest democracy ranks 140th, just two spots above Pakistan and 32 places below Kuwait. Newsgatherers and opinion-makers in India risk assassination, arbitrary detention and legal harassment, not to mention vicious and extremely well-organised internet trolls. The journalist Rana Ayyub, recently featured in Time magazine’s global list of 10 threatened journalists, is one of the many female public figures in India hounded by rape threats and fake pornographic videos.

Moreover, the colonial-era sedition law, which was once unleashed on freedom fighters, is used to torment a wide range of figures from the novelist Arundhati Roy to, recently, a former lawmaker who had praised Pakistan in a Facebook post for its tradition of hospitality.

In its election manifesto, India’s opposition Congress Party has promised to repeal the law. This sensible proposal has incited vituperative charges of treason from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. Contrary to what Modi claims, those martyred in Amritsar would not be proud of India today — a country in which even innocent children are detained preventively for prolonged periods, as a United Nations report on the human rights situation in Kashmir documented last year.

Indeed, the methods India and Pakistan use to govern their border states, from Balochistan in the west to Nagaland in the east, include rape and torture as well as preventive and indefinite detention. They arguably exceed, in their intensity and scope, as well as the culture of impunity they foster, what the martyrs of Jallianwala Bagh were protesting against.

Denouncing the Rowlatt Act in 1919, Jinnah said that “a Government that passes or sanctions such laws in a time of peace forfeits its claim to be called a civilised Government.” By this measure, neither the Indian nor the Pakistani government today can be called civilised.

Deploying British-inspired laws as a blunderbuss, while harnessing Silicon Valley’s innovations to illiberal causes, the ruling classes of India and Pakistan have established what Gandhi explicitly warned his compatriots against: “English rule without the Englishman.”

It is no doubt easy and gratifying to point to the atrocities of Western imperialism. But any principled anti-imperialist and democrat today can only feel anguish and shame over how, a century after the British army gunned down Rowlatt’s critics in Amritsar, his authoritarian mindset still rules South Asia.

— Bloomberg

Pankaj Mishra is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. His books include “Age of Anger: A History of the Present,” “From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia,” and “Temptations of the West: How to Be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet and Beyond.”