How safe are women in India’s biggest state?

The latest incident of sexual violence in Uttar Pradesh has come as a shock in India

‘You may trod me in the very dirt but still, like dust, I’ll rise.’ Over the years Mary Angelou’s words have inspired far beyond her intended audience, but for the woman and girl child of India — trodden, violated and hung dead from trees even this uplifting poem will fall short.

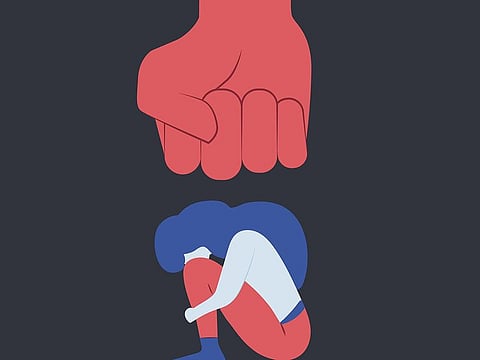

The image is hard to describe. Heartbreaking, brutal, frustrating, resignation — the emotions are intense and many. And yet it is a cycle that doesn’t pause, leave alone break. This time it reminds of another chilling crime eight years ago.

Two sisters belonging to a lower caste family were discovered dead hanging from a tree, they were positioned by their perpetrators in a way that they were facing each other. The sisters aged 17 and 15 were raped this month before being strangulated in Uttar Pradesh’s Lakhimpur Kheri, a heinous crime for which six men have been arrested. In 2014 two minor girls were found hanging after being raped by four men. It is the same state, only the tree has changed.

48 hours news cycle later, the two teenaged Dalit sisters vanished from the public glare, the staying power of ground reality when it comes to crimes against women and children is dismal. When it is the marginalised, the interest is even more slippery.

Just hours after the Lakhimpur news broke another girl in Uttar Pradesh died after battling for her life for days. She had been set on fire after an alleged gang-rape. A body of another minor Dalit girl was found in a jungle in the Budaun district of Uttar Pradesh. Her family alleges she too was raped before being murdered.

There are allegations that the local police misbehaved with parents of the murdered girls when they went to file a complaint. It is a sequel, the Dalit family of the Hathras rape victim was also treated as though they were the ones who had committed a crime.

For Dalit families closure comes with a price — their silence. It is not unknown for attackers to be shielded and in the Hathras gang-rape upper caste thakurs even took out a public rally in support of the accused. Low rate of convictions embolden, those who commit the senseless crimes are aware that justice and crime are not two sides of the same coin.

A dismal picture

In 2020, a staggering 96.5% cases were pending under the SC/ST Act with 177,379 cases awaiting trial under the legislation that was enacted to safeguard the lower castes and tribes.

The overall picture is equally dismal, data released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) last month for the year 2021 shows an upward graph of almost 20% increase in rape cases with 4.28 lakh crimes against women cases registered.

The statistics do not take into account sociocultural factors like fear, shame and stigma which compel families to not report, a trend more prominent in the Dalit and marginalised milieu. There are more Lakhimpur and Hathras, we just haven’t heard about them.

The state of Uttar Pradesh last year had more than 50,000 cases of crime against women, the highest in a country where 87 rape cases are reported daily on an average.

Where does the buck stop? Women need to realise that they mistakenly thought they mattered, but slogans came and went. A solution arises only when there is acceptance, we are faced with obduracy of silence.

Extreme gender-based violence like rape has its genesis in poverty, power, privilege and patriarchy. ‘Sexual terrorism continues to be the most extreme and effective way to enforce traditional gender roles, relations and dynamics. It constraints and subjugates women and keeps our sexuality, agency and transgressions in check,’ writes Tara Kaushal in her book Why Men Rape.

It is this power that was re-enforced few days earlier on a tree in a remote sugar cane field. The tree for its part has its own burden, in this tragedy of survival without a redressal it will be a witness to rural families clamping down on girls and their dreams. Two sisters died and countless other Indian girls lost.