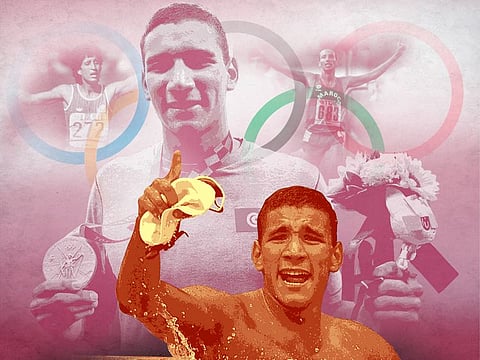

Arabs at the Olympics: Summer of Ahmed Hafnaoui

Reasons behind hyperbolic celebrations of individual achievements of few Arab athletes

Arab athletes have taken part in the summer Olympics for more than a century, ever since Egypt competed in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. But the summer of 1984 was special. It was the summer of Nawal El Moutawakel.

The Moroccan runner won the gold medal in the women’s 400 meters hurdles race at the Los Angeles Olympics; the first ever female Moroccan, Arab, Muslim, and African athlete to win to become an Olympic medallist. And that gold medal was Morocco’s first in an Olympic competition. It was also the first medal to be won in the women’s 400m hurdles, which was introduced for the first time in the games.

I still remember vividly the outburst of joy, and tears for many people as the petite 22-year-old Moroccan sprinter, with youthful looks and short curly hair, crossed the finish line on Aug. 8, 1984. Started in lane 3, she was trailing rest of the runners in the first half of the race, only to take off after two hundred meters, leaving everyone else behind. It was beautiful.

The original inspiration

Years later, Nawal told the BBC that she was not supposed to win that day. “I felt I could be in the final, like the top eight. I was really scared, but my coaches said I have to go from start to finish with strength, because I can win.” She did win and became not only a national hero in her country but in all Arab countries. The next day was a national holiday in Morocco and the late King Hassan II, in an unprecedented gesture, ordered that every newborn girl on Aug. 8 to be named Nawal!

Her story inspired thousands of women in the Arab world and beyond to pursue their athletic dreams, especially in place where women freedoms were restricted three decades ago. The International Olympic Committee marked the 20th anniversary of her Los Angeles victory with this well-deserved and gratifying tribute: “Nawal El Moutawakel was able to go all the way with her dream, despite the difficulties. She thus became an example of courage and perseverance for all athletes, and a model of success for all women.”

For a non-Arab, the hyperbolic celebration of what Nawal and few others — such as her compatriot Said Aouita, winner of the 5,000m gold medal in the same games, the Syrian Ghada Shuaa in 1996 and another Moroccan, Hisham Al Karrouj in 2004 — have achieved may seem exaggerated. But for an Arab, these few achievements are, of course, extraordinary.

Since the first Olympic Games in 1896, Arab countries lagged behind the rest of the world. For more than a century, the 22 Arab nations have won a meagre 118 medals, including 31 gold. Meanwhile, Australia, for example, have had nearly 500 medals. A small nation like Sweden have won around 650 medals. And forget about those giants like the United States and China, which in a single Olympic tournament win more medals than the Arabs have won throughout their participation history.

The Arabs’ failure in the Olympics or in the Fifa World Cup has a number of reasons that of course does not include the financial factor. Arab countries do not lack the financial resources, which is an essential aspect of building a successful sports team that is able to compete globally. There are other important factors that we fall short of.

No long-term planning

First is the lack of serious long-term planning. In places like Europe, Asia and North America, long-term sophisticated and empirically designed plans ensure the continuation of sporting excellence; plans that don’t change with the change in management. They remain consistent, developing generation after generation of competitive athletes in all games.

The Arab world has a great deal of sports talent and millions of young people with a lot of potential to compete, and inspired by Nawal, Said and Hisham. The problem lies in the absence of planning.

Secondly, unfortunately, we do not have a ‘sports culture’. Many officials in the Arab world in fact consider sports a waste of time and resources! Athletes, with the exception perhaps of football teams, are overlooked in the Arab world, especially in the individual games such as athletics.

They receive no attention or funding at all. Individual games such as track and field, tennis or swimming are the most important category of the Olympic games with the maximum number of medals. Regardless, we pay little official attention to them. In schools, for example, most children are encouraged to play football only.

Thirdly, we lack a suitable sports infrastructure that would attract and encourage sportspersons. We don’t have enough sports fields, courts (except for football pitches) in which ambitious young people can train and get the necessary experience to compete. In short, the making of an Olympic champion is a national art and takes a lot of hard work. Unfortunately, in the Arab world, we lack this art.

It is understandable that we feel this collective ecstasy when an Arab athlete wins a medal against all those unsurmountable odds. And in every Olympic, there is at least one extraordinary individual who lights a candle in our sports darkness.

For me, in the Tokyo games, there are at least three champions who surely are a source of pride. One of them, Tunisian swimmer Ahmed Hafnaoui, actually deserves to get the Arab Olympic summer named after him, just like we called the summer of 1984 in the name of Nawal El Moutawakel.

A star is born

He is only 18 and won a shock gold medal in the men’s 400m freestyle. He qualified to the final race as the slowest swimmer in the heats. But in the final, which the more experienced Australian Jack McLoughlin was expected to win easily, it was Hafnaoui’s day. He came from the outside to beat the decorated Australian swimmer with a time of three minutes 43.36 seconds.

“It is a dream and it became true. It was great, it was my best race ever,” the Tunisian youth told the media following his gold medal coronation. He never in fact thought he would be a contender in that race in Tokyo. He said he was preparing himself in this Olympic to compete for a medal in the next Olympic (Paris 2024).

Two more people made us proud in the Tokyo Olympics. The first is the 12-year-old Syrian table tennis player Hind Zaza, the youngest competitor at the Tokyo games. She expectedly lost her first-round match 4-0 to Chinese-born Austrian veteran Liu Jia, but she was a worthy opponent, genuinely projecting all the marks of a future serious contender.

The other is Sara Gamal, the Egyptian basketball referee. A civil engineer by profession, Sara became the first hijab-wearing Muslim woman to referee basketball at the Olympic Games. Not only that but she is also the first Arab and African woman to officiate 3x3 basketball at the Olympics. Another first for an Arab woman.

These inspiring individuals, and their stories will surely motivate many more youth in the Arab world to train and compete. For me, though, Hafnaoui is in a league of his own, considering the years-long political turbulences in his home country. He is my hero this summer, the summer of Ahmed Hafnaoui.